Prevalence, Demographic, and Clinical Variables

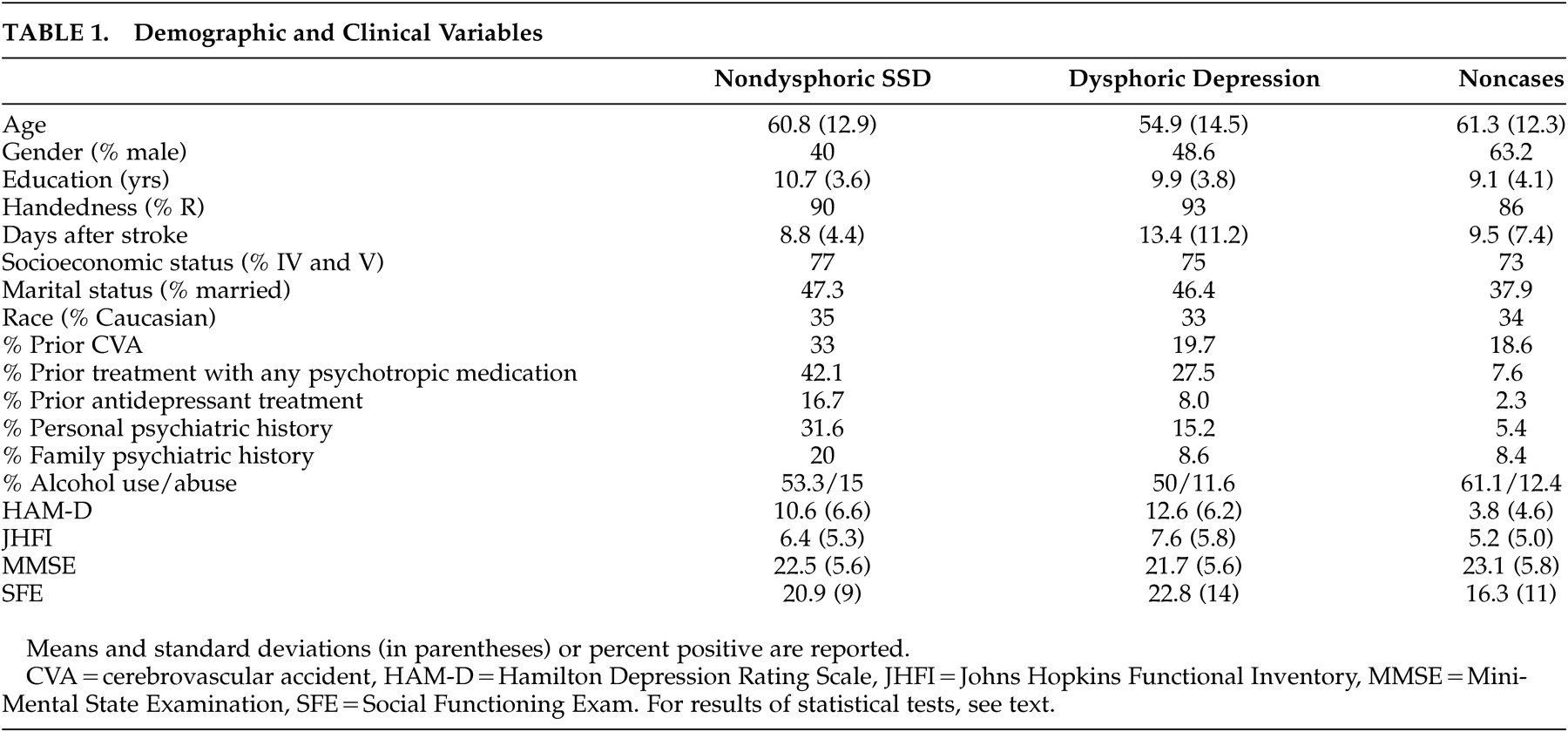

There were 20 (6.6%) subjects meeting criteria for nondysphoric subsyndromal depression, whereas 107 (35%) constituted the dysphoric group. Of these, 55 met criteria for minor depression and 52 met criteria for major depression. Demographic and clinical variables data are shown in

Table 1 .

A significant group effect of age was found ( F [2, 290]=7.7, p<0.0001), with dysphoric patients being younger than noncases (p<0.05). No other post-hoc test reached statistical significance. Female sex was significantly more frequent in both depression groups compared to nondepressed comparison subjects (chi-square [2]=8.1, p<0.02), but dysphoric and nondysphoric depression did not differ (chi-square [1]=.5, p>0.4).

No group effect of race, handedness, education, socioeconomic and marital status, history of prior stroke, psychiatric family history, or alcohol consumption or abuse was found to be statistically significant. A group effect for personal psychiatric diagnosis was found be statistically significant (chi-square [2]=16, p<0.001), but the difference between dysphoric and nondysphoric did not reach statistical significance (chi-square [1]=3.2, p=0.074). Consistent with this finding, a significant group effect of prior treatment with any psychotropic medications was found (chi-square [2]=33, p<0.0001, but there was no difference between dysphoric and nondysphoric depression (chi-square [1]=1.1, p>0.2). Twice as many nondysphoric subsyndromal depression subjects were treated with antidepressants before the occurrence of the stroke compared with persons with dysphoric depression (16.7% versus 8%). Subjects with this condition were also treated more frequently (5% versus 0%) with antipsychotics and other psychotropic medications (11% versus 1%) (whole model statistics for all drug categories, chi-square [8]=26.8, p<0.001).

Psychopathology and Impairment Variables

As expected based on our inclusion criteria, a significant group effect for severity of depressive symptoms was found (

F [2, 294]=92, p<0.0001), with both dysphoric and nondysphoric disorders showing greater symptom severity compared to nondepressed controls (p<0.05) (

Table 1 ). The difference between dysphoric and nondysphoric depression groups was not statistically significant (p>0.05).

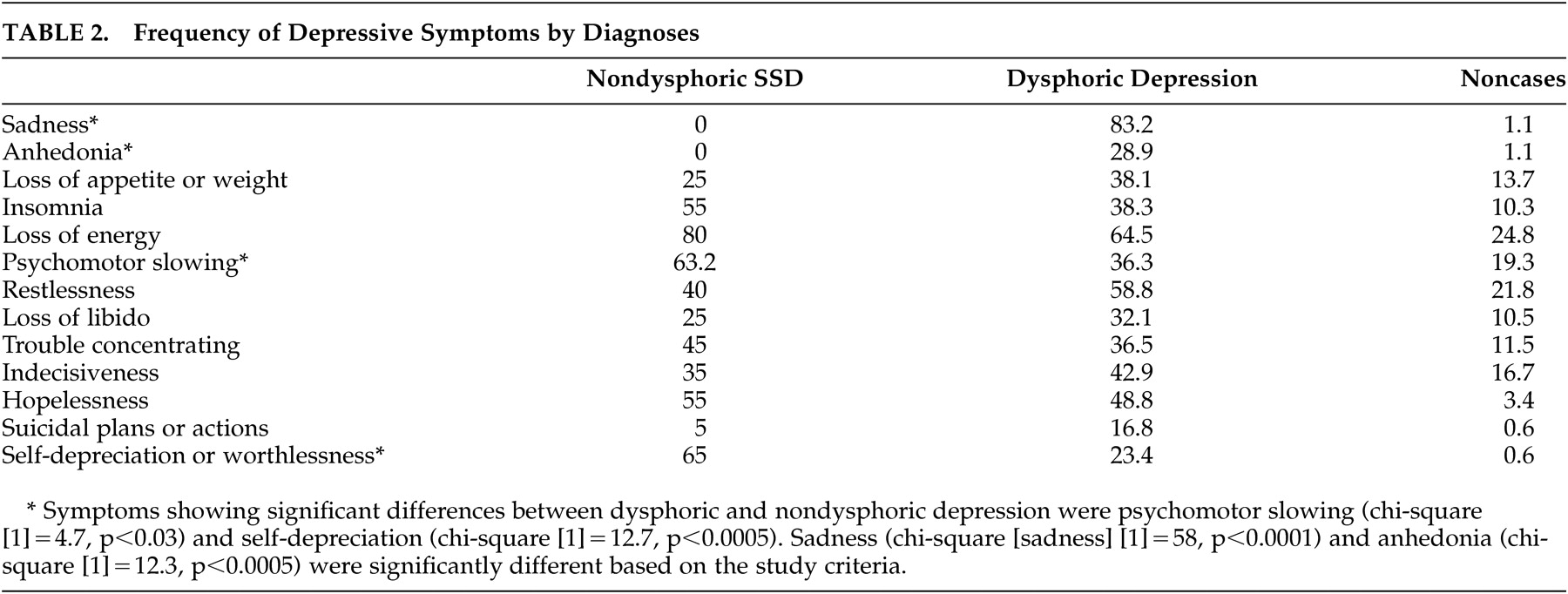

The frequency of affective, cognitive, and vegetative symptoms of depression is shown in

Table 2 . Affective symptoms were significantly more frequent in the dysphoric than the nondysphoric subsyndromal depression group. All overall effects were highly significant, as expected (chi-square values between 16 and 87, p values <0.0003 or better in all cases). Statistically significant differences between nondysphoric subsyndromal depression and dysphoric depression included psychomotor slowing and self-depreciation (

Table 2 ).

In addition, there were quantitative and qualitative group differences in the emotion-related psychopathology. While there was no subject in the nondysphoric subsyndromal depression and comparison groups acknowledging either moderate or severe “emptiness of all feelings and lack of ability to react emotionally,” 36% (24.8% moderate and 11.4% severe) of subjects in the dysphoric depression group did endorse this symptom (chi-square [4]=87.0, p<0.0001); the difference between dysphoric and nondysphoric depression was also statistically significant (two-tailed Fisher’s exact p<0.003). In addition to this symptom, there was a significant overall effect for the psychopathological sign “sad affect,” which was present in 52.6% of nondysphoric subsyndromal depression patients (11.5% moderate and 42.1% severe), in 65% of dysphoric depression subjects (49% moderate and 16.3% severe), and in 14.6% (12.7% moderate and 2.9% severe) of controls (two-tailed Fisher’s exact p<0.002). The difference between dysphoric and nondysphoric depression on moderate or severe sad affect was also statistically significant (two-tailed Fisher’s exact p<0.002), meaning that nondysphoric subsyndromal depression patients had greater likelihood to show more severe sad affect compared to dysphoric depressed patients. In aggregate these data signify that while patients with nondysphoric depression did not endorse emotional psychopathology, observation of their affect was consistent with a depressive disorder.

Severity of impairment in activities of daily living also showed a significant group effect ( F [2, 294]=6.6, p<0.002), with nondysphoric subsyndromal depression lying between dysphoric depression and noncases, but only the dysphoric group was significantly different compared with noncases (p<0.05). Satisfaction with social functioning showed a significant group effect ( F [2, 212]=6.51, p<0.002). While nondysphoric subsyndromal depression social functioning was between the values of the dysphoric group and noncases, only dysphoric depression was significantly different from noncases in post-hoc tests (p<0.05). In addition, differences in cognitive functioning were not found to be significantly different ( F [2, 281]=1.6, p>0.2).

Localization of Brain Damage

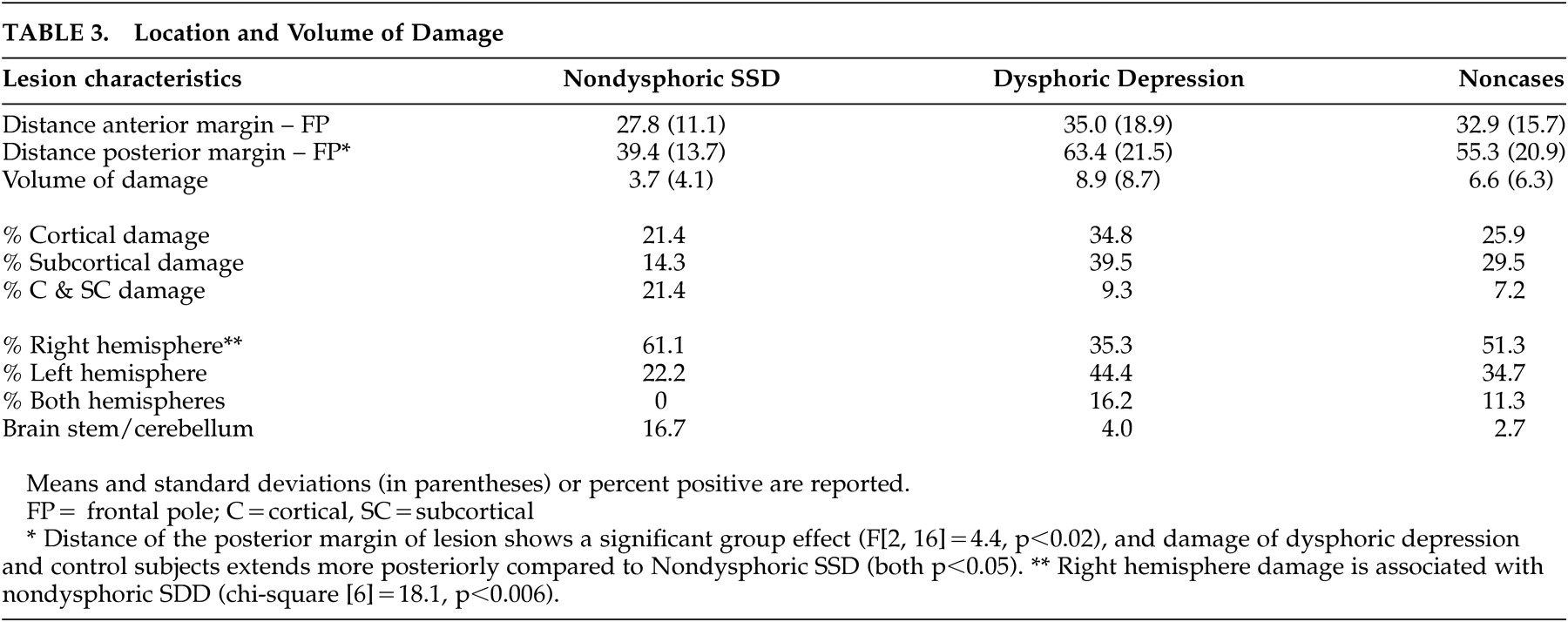

For subjects who received a head CT, a brain lesion was found in eight nondysphoric subjects (57.1%), 36 dysphoric depressed subjects (83.7%), and 87 controls (62.6%) (chi-square [2]=7.2, p<0.03). There were six subjects (42.8%) in the nondysphoric, seven in the dysphoric (16.8%), and 52 in the control group (37.4%) where a repeat head CT did not reveal a brain lesion.

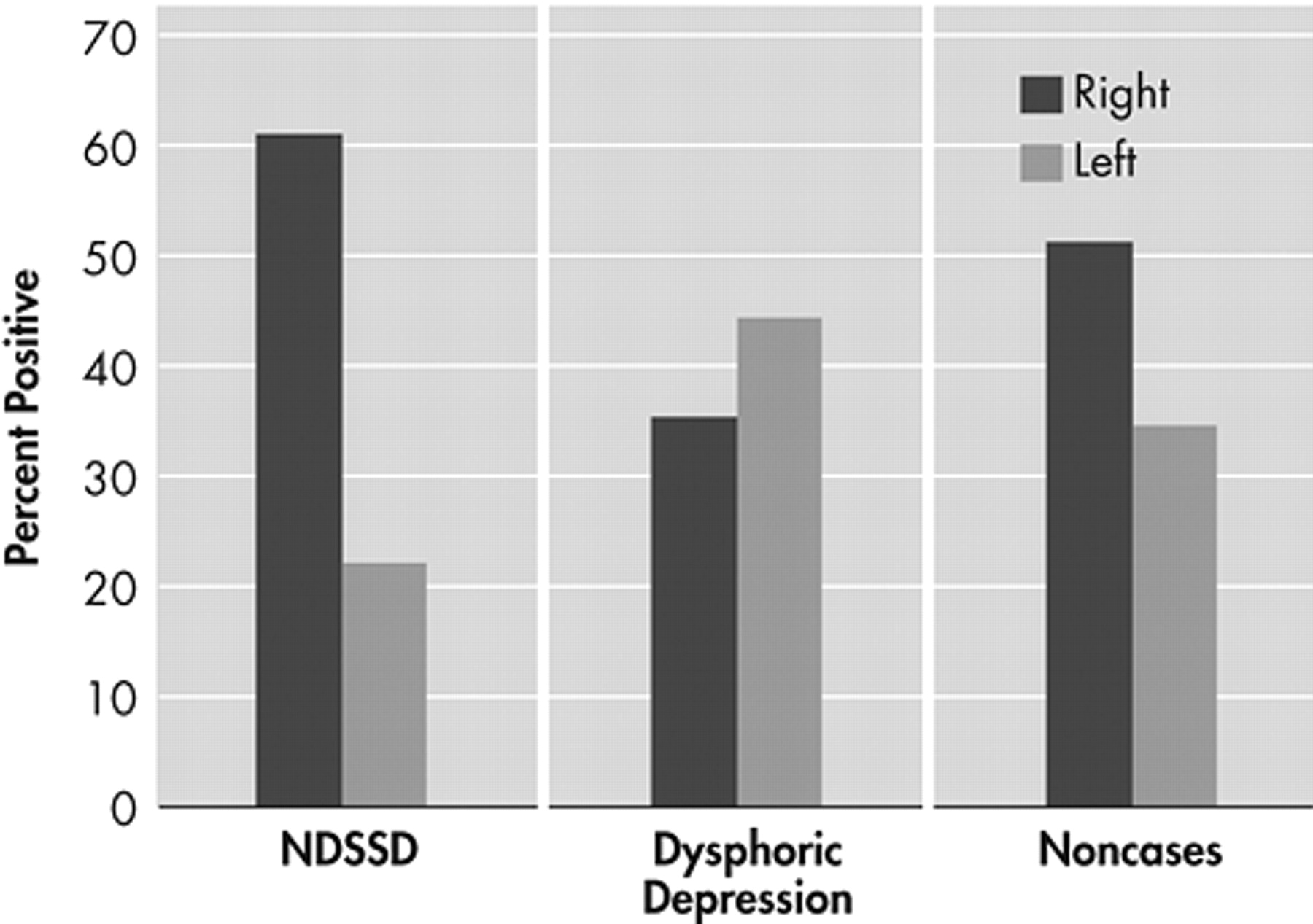

Our main hypothesis of a significant association between nondysphoric subsyndromal depression and right hemisphere lesion was substantiated (i.e., 61% of the patients with this condition, 35% of the dysphoric subjects, and 51% of controls had a right hemisphere lesion (chi-square [6]=18.1, p<0.006) (

Table 3 ). Comparing only dysphoric and nondysphoric depressed subjects with single unilateral lesions revealed an effect of hemispheric side of lesion (chi-square [1]=4.4, p<0.04) (

Figure 1 ).

While the distance of the anterior margin of the damaged area to the frontal pole was comparable across the three groups ( F [2, 140]=0.56, p>0.5), the distance of the posterior margin showed a significant group effect ( F [2, 16]=4.4, p<0.02), demonstrating that the damage in dysphoric and control patients extended significantly more posteriorly compared to nondysphoric subsyndromal depression patients (p<0.05 in both cases). There was no significant group association with volume ( F [2, 144]=2.1, p=0.12), or damage to cortical or subcortical regions (chi-square [4]=3.7, p>0.4). In summary, analyses of the location of the damage support our hypothesis that nondysphoric depression is associated with right hemisphere damage localized to more anterior structures than dysphoric depression.