To the Editor: In 1885, Georges Gilles de la Tourette described a nervous disease characterized by lack of motor coordination, echolalia, and coprolalia.

1 Later, the disease became known as Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome and includes both verbal and motor tics with onset before the age of 18. Verbal tics may be simple (e.g., meaningless fonatory sounds, throat clearing, barking, etc.) or, less commonly, complex (coprolalia, echolalia, etc.), while motor tics are sudden, fast, repetitive, nonrythmic, stereotyped involuntary movements which may include blinking, facial grimacing, jumping, sniffing, or echopraxia.

According to Jankovic and Rohaidy,

2 sleep disturbances accompany Tourette’s syndrome in 60% of cases. Nevertheless, no particular sleep disorder has been identified for this disease, although rhythmic periodic movements,

3 REM sleep behavior disorder

4 and parasomnias

5 are commonly described. Concerning sleep architecture, only a few polysomnographic studies have been reported with controversial results. Only in a recent well-controlled study, Cohrs et al.

6 found difficulties initiating and maintaining sleep, reduced sleep efficiency, an increase in stage 1 sleep, multiple arousals, as well as a decrease in slow-wave sleep.

Standard pharmacological treatment for Tourette’s syndrome includes antidopaminergic drugs. Silay and Jankovic, in a more recent review,

7 stated that along with behavioral interventions, haloperidol and pimozide (dopaminergic antagonists) are the only two pharmacological agents approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of Tourette’s syndrome.

In view of the fact that blockade of dopaminergic systems may in itself induce sleep disturbances,

8 we decided to analyze the sleep pattern of a 12-year-old patient with Tourette’s syndrome before and after treatment with the antidopaminergic agent risperidone, an atypical antipsychotic previously reported effective in the treatment of Tourette’s syndrome.

9,

10Methods

A 12-year-old boy with no previous psychopharmacological treatment was diagnosed as having Tourette’s syndrome, according to DSM-IV criteria. Following medical and neuropsychological evaluation, signs of attention deficit disorder and depression (i.e., anhedonia and hopelessness) were found.

EEG Recording

The patient was studied in the Sleep Disorder Center of the Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana in Mexico City. To discard additional EEG abnormalities, a 10/20 head mount was installed along with standard polysomnography recordings, including facial and limb electrodes, respiratory bands, and a microphone to record snoring and vocalizations. The patient was videotaped throughout the night. The study initiated at 10 p.m. and ended at 7 a.m. the next day. Sleep staging was done according to Rechstschaffen and Kales standard criteria.

11 Arousals were scored according to criteria of the sleep disorders atlas task force of the American Sleep Disorders Association.

12After the first clinical and polysomnographic assessment, treatment with risperidone was initiated (1 mg daily during the first month followed by 2 mg daily the next 5 months). Monthly follow-up interviews were carried out and a final clinical and polysomnographic examination was completed 6 months later.

Results

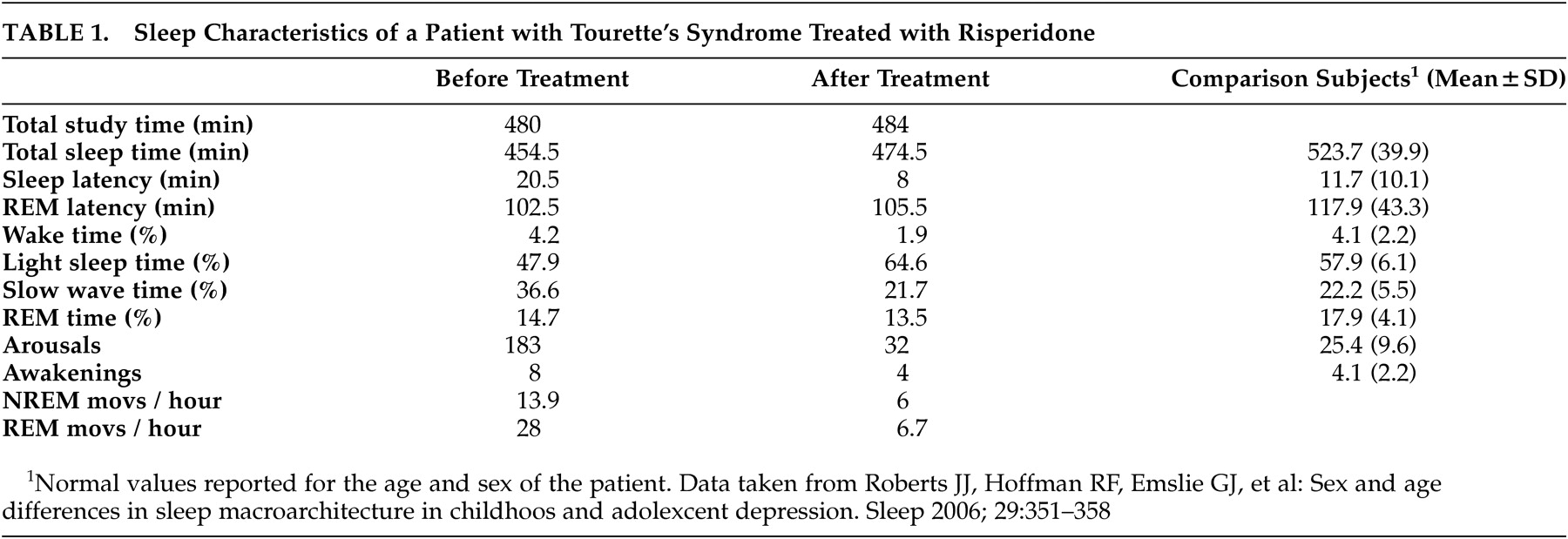

Table 1 shows data from the first and second polygraphic studies. As can be seen, sleep latency, percentage of slow wave sleep, and total number of arousals and movements, both in NREM and REM sleep, clearly decreased, while sleep efficiency and the percentage of light sleep increased. The third column, designated “Comparison Subjects,” shows data from a study recently published by Robert et al.

13 involving children of the same age as our patient. Comparison between our patient’s second study and the comparison subject’s shows the results to be quite similar.

After 3 months of treatment, motor and vocal tics remitted, and clinical improvement was maintained throughout the next 3 months. Additionally, the final neuropsychological evaluation after 6 months of treatment found marked improvement in mood and self-confidence, with no clinical signs of depression.

Discussion

The present case report supports the atypical antipsychotic drug risperidone as an effective treatment for Tourette’s syndrome, in accordance to previous short-term evaluation studies.

10 To our knowledge, this is the first time this agent has been evaluated after long-term administration in a patient with Tourette’s syndrome, with satisfactory results with regard to safety and efficacy. In addition, the relationship between Tourette’s syndrome severity and sleep disturbances was confirmed,

14,

15 since pharmacological treatment corrected both disturbances.

Our polygraphic observations in the first study concur with previous reports, and we believe that discrepancies in the literature concerning sleep alterations in Tourette’s syndrome are probably due to individual differences on manifestations of the disease.

Finally, the evidence in our study suggests that blockade of dopaminergic systems with the antipsychotic risperidone reverts both Tourette’s syndrome symptoms and sleep disturbances, thus implying that sleep disturbances are part of the biochemical alteration of Tourette’s syndrome, and not an aggregated disease.

The authors want to express their gratitude to Dr. Aldebaran Prospero and to Edith Monroy for the skillful review of the language of the text.