H untington’s disease is an autosomal dominant hereditary disease, characterized by movement disorders (chorea), behavioral disturbances, and eventually dementia. Although choreatic movements are often the most prominent signs, neuropsychiatric manifestations cause the most significant burden for the patient as well as for caregivers. Psychosis, affective disturbances, and personality changes with prominent apathy, irritability, or obsessive-compulsive features are all very common in Huntington’s disease, depending on the stage of the disease.

1 In early stage Huntington’s disease, affective disturbances and especially depression are common. Up to 40% of patients with Huntington’s disease suffer from depression in these early stages, and as the disease progresses, personality changes become more prominent, and further cognitive deterioration and dementia occur, often accompanied by paranoid psychotic symptoms.

1 Apathy is often encountered in patients with cerebral disease and has received more attention in Huntington’s disease in recent years. The prevalence of apathy increases with the stage of the disease, and correlations were found between apathy and cognitive decline in Huntington’s disease and also between apathy and number of CAG repeats, although findings are not unambiguous.

2,

3 The clinical presentation of depression and apathy in Huntington’s disease is the main subject of our study. Next to major depressive disorder, as described in the DSM-IV, subsyndromal or minor depression and apathy are often prominent and may co-occur with depression.

4 The precise relationship between apathy and depression in Huntington’s disease is unclear. As with Parkinson’s disease, stroke, and other cerebral diseases, depression and apathy in Huntington’s disease may be consequences of degenerative cerebral changes. The syndromal approach, according to the DSM-IV criteria, could hinder research on behavioral disturbances in Huntington’s disease. Craufurd et al.

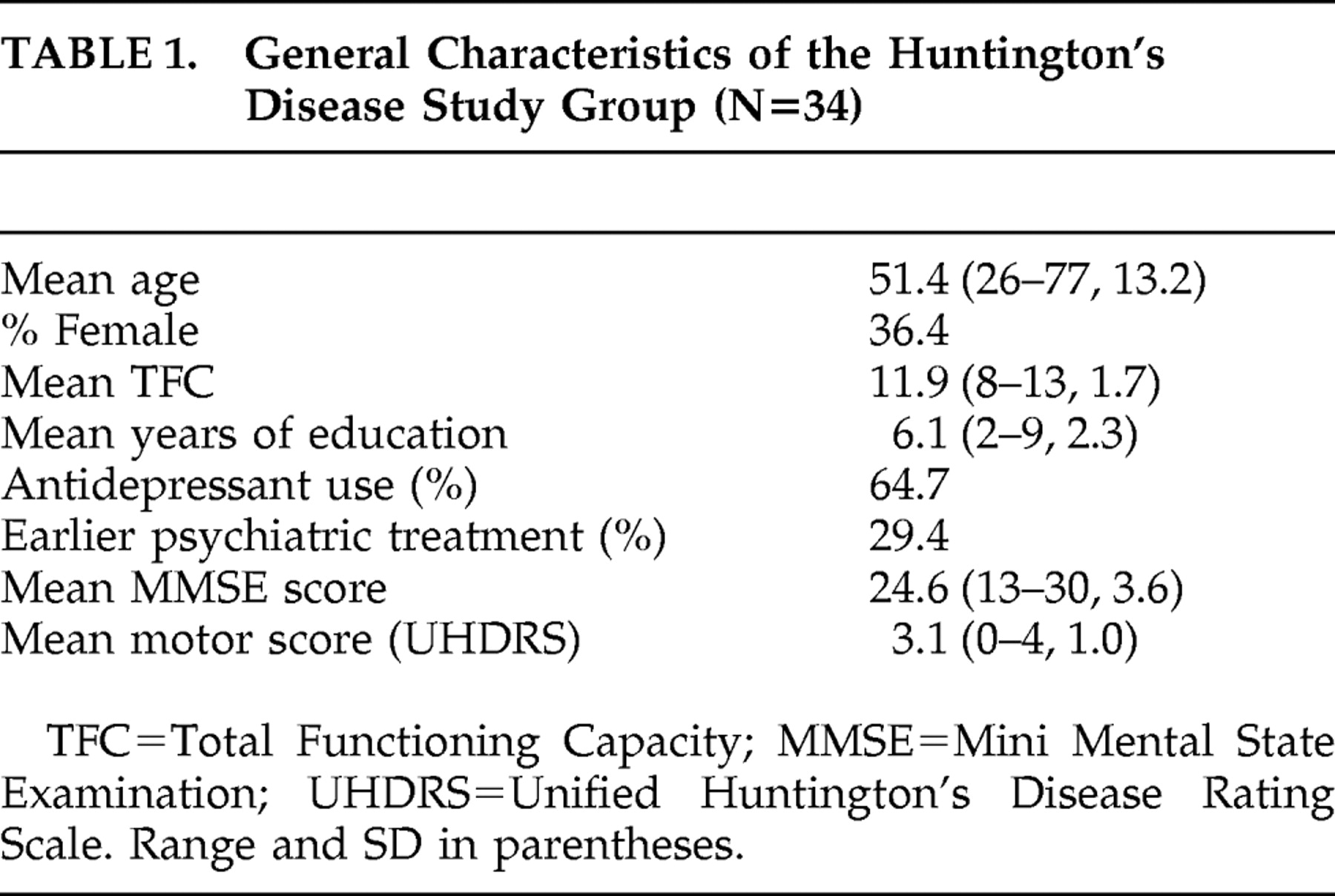

3 have suggested a more dimensional approach and developed a specific scoring tool to achieve this. We applied different diagnostic tools to study the relationship between syndromal depression and dimensional measures of observed behavior and apathy in 34 mildly to moderately ill Huntington’s disease patients. In this cross-sectional study, our aim was also to confirm earlier findings of progressive apathy in advancing Huntington’s disease.

DISCUSSION

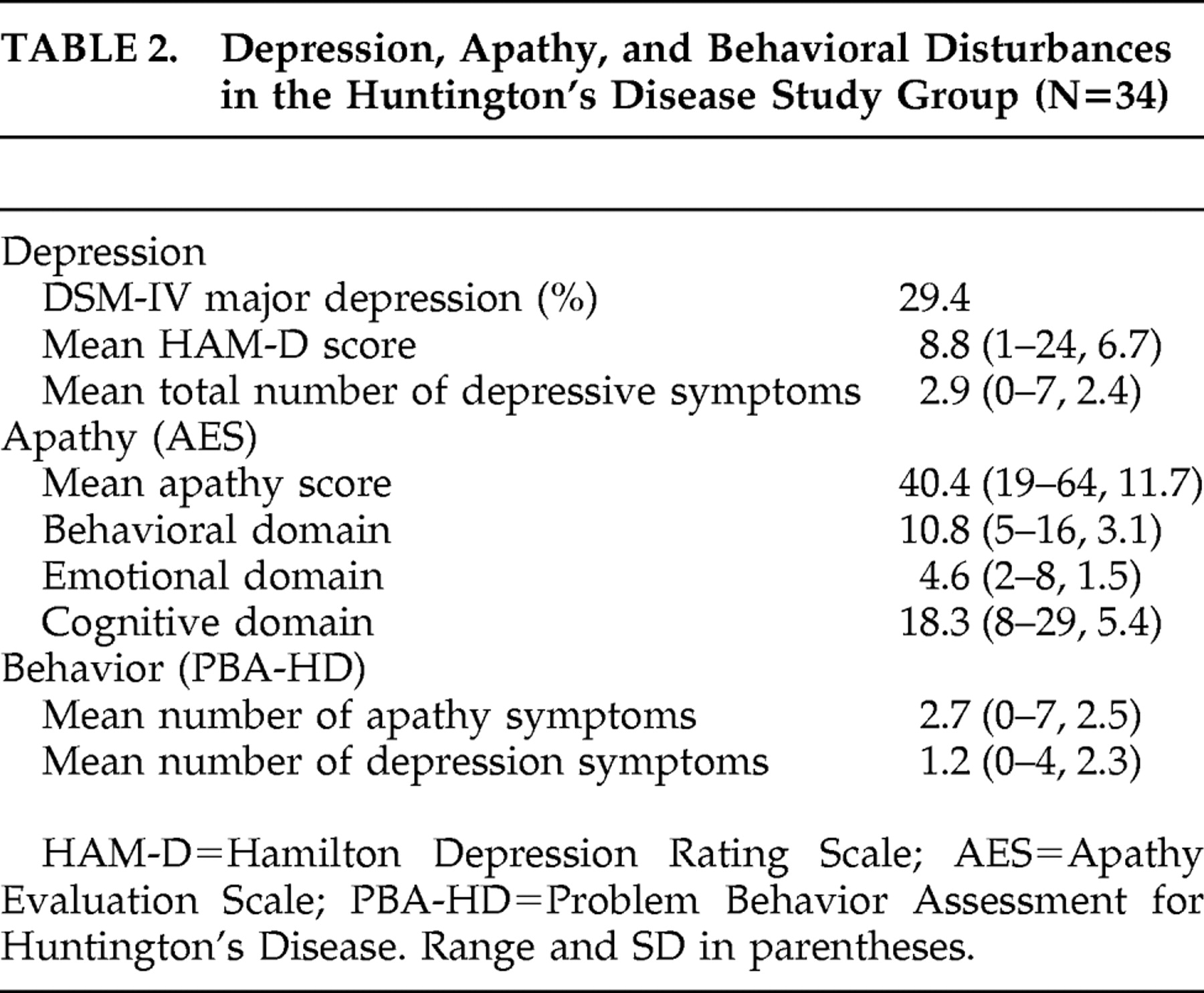

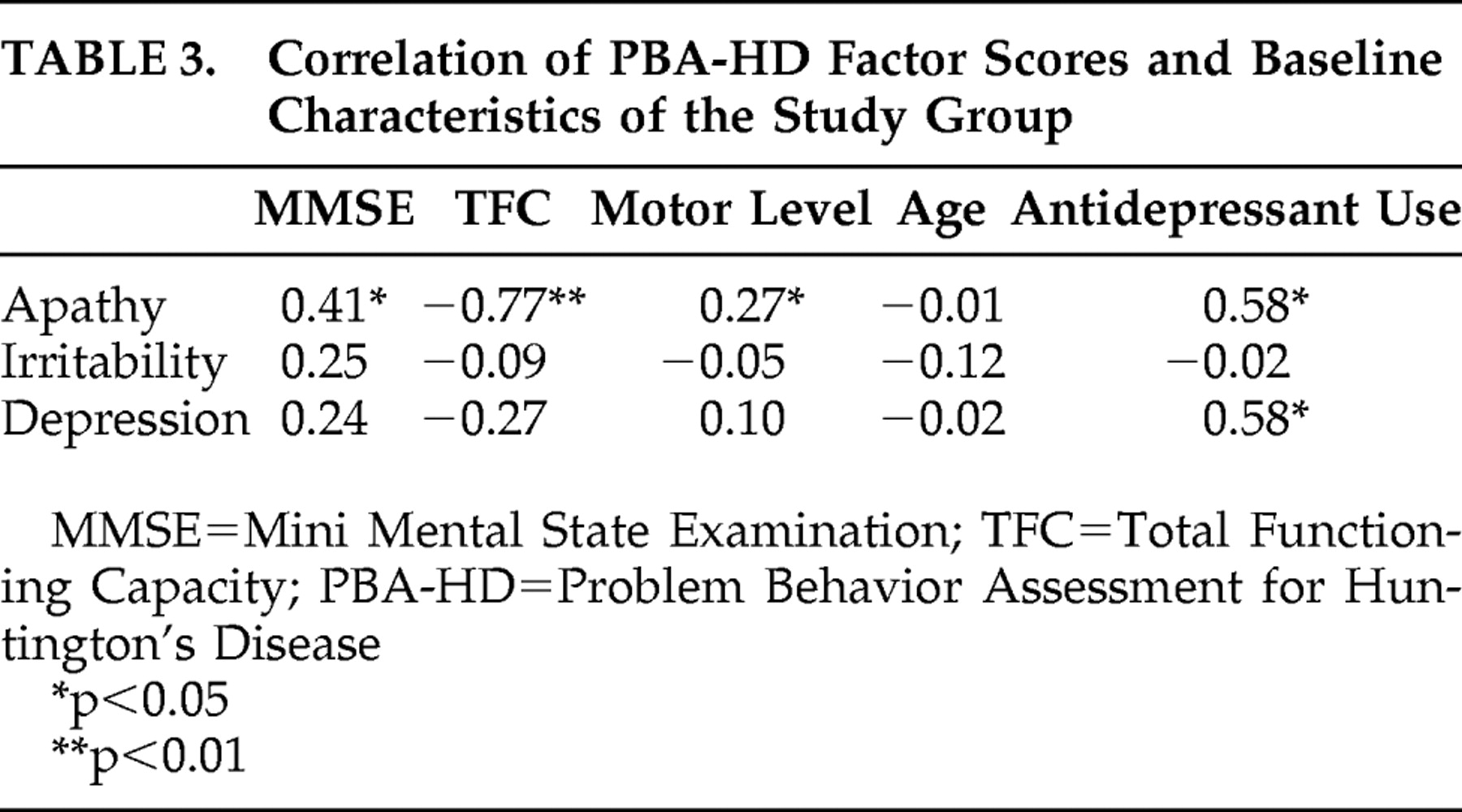

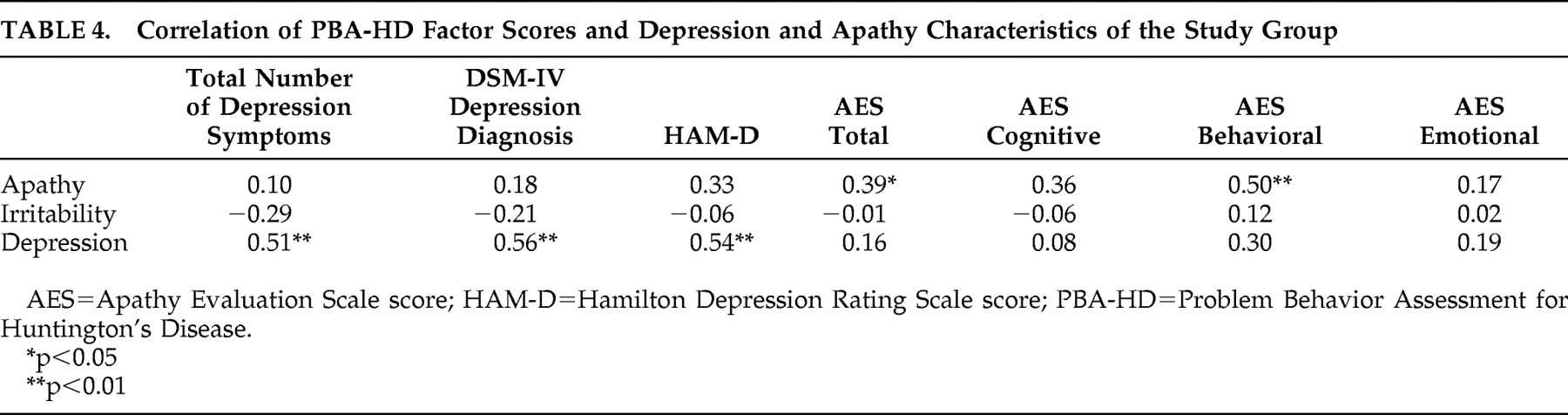

This study is one of the few focusing on the relationship between depression and apathy in Huntington’s disease. The main finding is that apathy is far more common than depression in Huntington’s disease. Moreover, apathy and depression are not related but are largely distinct dimensions, and we found that apathy was linked to other clinical characteristics such as cognitive deterioration and functional decline, whereas depression was not. In other words, apathy was more frequent in more advanced stages of Huntington’s disease. The fact that depression is an early event in Huntington’s disease, and the possibility that older age and cognitive deficits are related to apathy, may explain the dissociation between apathy and depression. In our study there was no correlation between apathy and age.

Our findings are supported by the results of other studies. Hamilton et al.

10 found that a composite apathy/executive dysfunction behavioral index strongly correlated with decline in activity of daily living. Another study on apathy and depression in Huntington’s disease also showed an association of the presence of apathy with frontal, cognitive measures, with no such association for depression.

2 Although this study used another measure for apathy that makes comparisons difficult, the major findings of it are in accordance with ours. Our findings concur with those of Thompson et al.

11 Our PBA-HD results also confirmed the findings of the Craufurd et al.

3 study regarding the different domains of problem behavior.

Although we included participants with early stages of Huntington’s disease and only mild functional disability, the number of patients with apathy was quite high in our study. This was in line with the study of Baudic et al.,

2 who studied a similar group of subjects and underlined the fact that apathy is a major problem even in early and middle stages of Huntington’s disease and that it co-occurs with cognitive decline as measured with the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale. The mean AES score in our group was 40.3, and more than half of our subjects scored over 40 on the AES. Although there are no reliable AES cutoff scores that separate apathetic from nonapathetic subjects, earlier reports suggested “normal” scores between 25–35. In his original publications Marin described “healthy” elderly having a mean AES score of 26 and “severely depressed subjects” having a mean score of 40.5.

8 Our participants showed only minimal to moderate levels of depression, but nonetheless could be considered to show symptoms of severe apathy.

Marin

4 and others have also observed dissociation between apathy and depression

12 in several groups of patients with other forms of cerebral pathology. Apathy is often observed in combination with advanced cerebral disease and cognitive dysfunction and may interfere with successful rehabilitation (e.g., in patients with traumatic brain injury).

13 In one study on apathy in various neurological disorders that included a group of 35 Huntington’s disease patients, Levy et al.

12 concluded that there was no clear correlation between apathy and depression measurements. As in our study, they found apathy to be highly prevalent in both the Huntington’s disease group and in other groups of subjects with various other cerebral diseases. Apathy was detected in 59% of Huntington’s disease patients (20/34), in 33% of patients with Parkinson’s disease (13/40), in 80% of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (24/30), and in 91% of progressive supranuclear palsy patients (20/22). They also found a correlation between the severity of apathy and the degree of cognitive decline in all of these diseases.

Both in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and in patients with vascular dementia, we found in previous studies that more advanced dementia was associated with the apathetic aspects of depression rather than the mood-related aspects.

14,

15 Furthermore we found that these depressed patients with a symptom profile with predominant apathetic features also showed specific neuropsychological deficits, with a negative correlation between these symptoms and the results on frontal tasks.

16,

17Only a few studies observed a major overlap between depression and apathy in patients with neurological cerebral disease. Starkstein

18 assessed subjects with Alzheimer’s disease with the AES and found apathy in 37%, with 64% of these subjects also fulfilling criteria for depression. A similar assessment of depressed elderly subjects without Alzheimer’s disease showed that 32% of these also fulfilled criteria for apathy. They found a correlation between the severity of apathy and cognitive deterioration in the Alzheimer’s disease group. Kant et al.

19 studied apathy in subjects with personality changes and mood disorder after closed head injury. They found that apathy and depression occurred separately in about 10% of subjects and occurred in combination in 60%.

Contradictory findings regarding the relationship between apathy and depression are probably due to methodological issues. These include the clinical stage of Huntington’s disease, the different assessment methods used in diagnostic practice, and the lack of a “golden standard” definition of both apathy and depression.

One of the strengths of our study is that the broad and comprehensive psychiatric evaluation of the patients was not restricted to DSM-IV diagnosis, but was directed at a broader range of psychiatric and behavioral dimensions. Other limitations may be the selection of patients with early- to middle-stage Huntington’s disease and the fact that we could not control for age and use of medication. Nevertheless, our study contributes to the construct validity of the concept of apathy in Huntington’s disease; ratings of apathy with the Problem Behavior Assessment do correlate with those of the Apathy Evaluation Scale (convergent validity), while ratings of depression on the Problem Behavior Assessment do not (divergent validity).

In conclusion, our results indicate that apathy and depression are separable and independent behavioral dimensions in Huntington’s disease, with apathy in Huntington’s disease related to neurodegeneration and connected to cognitive dysfunction and functional decline. It is a prominent feature of early- and middle-stage Huntington’s disease and, due to its major effect on daily functioning and quality of life, could be an important target for therapeutic interventions in the near future. Based on current knowledge, depression in the early stages of Huntington’s disease should be treated like other forms of depression, with selective serotonin inhibitors as a first choice and subsequent steps based on the treatment guidelines. When apathy becomes a dominant feature, success of conventional antidepressant medication may be limited.

20 One conspicuous finding of our study was that many of the participants, whether depressed or not or apathetic or not, received antidepressants. In the future, other options such as dopaminergic antidepressants or psychostimulants as a specific medication targeted at apathy should be studied.