W e have previously reported anecdotal evidence of sertraline’s potential to improve executive control function in elderly patients with depression.

1 However, depression is psychometrically similar to ischemic cerebrovascular disease.

2 –

3 Both conditions are characterized by prominent executive impairments in the absence of clinical phenomena, such as aphasia, amnesia, or apraxia, which characterize neocortical lesions outside the frontal lobe.

We have labeled this syndrome “type 2 dementia” to explicitly distinguish it from the neocortical (type 1) clinical syndrome of Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders.

4 Type 2 dementia is sometimes characterized as “cognitive impairment no dementia,”

5 or dysexecutive “mild cognitive impairment.”

6 In the setting of ischemic cerebrovascular disease, type 2 dementia characterizes a subset of cases with “vascular cognitive impairment.”

7All these nomenclatures emphasize the absence of “dementia” (i.e., clinical features that characterize Alzheimer’s disease’s neocortical pathology). However, in our opinion, isolated executive impairment is worthy of consideration as a true dementia in the sense that it is an acquired disorder of cognitive impairment in a clear sensorium sufficient to cause disability. This is because of executive function’s relatively strong and specific association with disability.

8 In contrast, “dysexecutive mild cognitive impairment” may be an oxymoron that cannot survive explicit functional status assessment because that would reveal (executive) cognitive-related disability, a

sine qua non of the dementia syndrome.

9 –

10Given the phenomenological overlap between the “type 2” presentations of depression and ischemic cerebrovascular disease, and our anecdotal experience with sertraline’s effects on executive control function in both conditions, we decided to conduct a retrospective chart review of our clinic’s experience with open-label use of sertraline for the treatment of nondepressed patients with ischemic cerebrovascular disease and type 2 dementia, as a prelude to future placebo controlled clinical trials.

METHODS

Case Selection

This is a case series of 35 consecutive nondepressed outpatients with ischemic cerebrovascular disease who were treated with sertraline monotherapy in the Geriatric Evaluation and Management: Memory Clinic number two (GEM MEM2) at the South Texas Veterans Health Care Administration’s Audie L. Murphy Memorial Veterans Administration Hospital in San Antonio, Texas.

The purpose of our clinic is to evaluate and treat patients with isolated executive control function impairment. Patients are usually referred by primary care physicians in the South Texas Veterans Health Care Administration network on the basis of subjective “memory loss” or “cognitive impairment.” During their initial assessment, patients are administered the Executive Interview (EXIT25)

12 and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)

13 or its equivalent. Nonpsychotic patients who score >15/50 on the EXIT25 and >23/30 on the MMSE are withdrawn from their psychotropics and referred for treatment of their executive impairments. We have previously determined that a high fraction of patients who meet these criteria can be diagnosed with potentially reversible non-Alzheimer’s disease conditions, including ischemic cerebrovascular disease. A high prevalence of ischemic cerebrovascular disease among elderly patients diagnosed with “type 2” dementia on the basis of their EXIT25 and MMSE scores has been confirmed by others.

14All patients undergo a dementia work-up that includes serum B12, folate, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), hematocrit, and MRI. Since no medication has been approved for the treatment of executive control function impairment, and since GEM MEM2 patients do not generally meet criteria for Alzheimer’s disease, treatment in this clinic is empirical and generally off-label. A notable exception is treatment for depression. All GEM MEM2 patients who screen positive for clinical depression receive antidepressants.

A major goal of the clinic is to ameliorate executive impairment. Since the EXIT25 is strongly associated with functional outcomes across a wide range of conditions,

8 it is used as the primary measure of the treatment efficacy. The EXIT25, MMSE, and the executive clock-drawing task (CLOX)

15 are obtained at every visit. These measures, supplemented as needed by additional testing, are administered by the resident house staff or geriatric fellows. House staff attend the clinic for the entire year, enhancing continuity of care.

GEM MEM2 faculty members develop individualized treatment plans in conjunction with the house staff. Treatment generally begins with a high dose sertraline trial, regardless of the patient’s depressive symptom burden, as our anecdotal experience has strongly supported its use.

1 Other GEM MEM2 treatment plans are predicated on the neurophysiology of the fronto-thalamocortical circuits that have been associated with executive control function.

16 However, only the results of sertraline monotherapy trials are reported in this communication.

Sertraline is generally started at 50 mg and titrated, at 25 mg intervals, to 75–100 mg/day over 4–6 weeks. At the patient’s first follow-up assessment (visit 1), a decision is made whether to abandon sertraline, augment with a second agent, or increase to 100 mg/day. The dose is then titrated by 50 mg increments toward 200 mg/day. By the third follow-up visit (visit 3), patients have generally been taking 150 mg/day for 4–6 weeks. During this trial, comorbid medical problems would have been treated by each patient’s primary care physician and are not considered here, with the exception of hypothyroidism or B12 deficiency, both of which were exclusionary for the purposes of this review.

Our clinic has a computerized medical record which helps standardize patient encounters and facilitates record reviews, such as this one. Our record review has been approved by both the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio’s institutional review board and the Audie L. Murphy Memorial Veterans Administration Hospital’s Research and Development Committee.

Case Selection Criteria

All patients (N=48) treated in the GEM MEM2 clinic with sertraline monotherapy between February, 2005, and October, 2007, were considered. Two cases each had two distinct sertraline trials during this period. Of these 50 trials, five cases with baseline Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) scores >9/15 were excluded. Two cases each with abnormal B12 (<180 pg/ml) or TSH levels (>4.5 μU/ml) were excluded. All patients received neuroimaging as part of their dementia work-ups. Only cases with confirmed ischemic cerebrovascular disease were included. Seven cases with normal exams, hydrocephalus, hygromas, regional cortical atrophy or either focal hemorrhagic or space-occupying lesions were excluded.

Clinical Variables

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the 15 item short form of the GDS.

17 Gerety et al.

18 have found no differences among the 30-item GDS, the 15-item GDS or the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as screens for depression in elderly patients from our VA (sensitivity [range=0.74–0.89], specificity [range=0.62–0.77], or area under the receiver operating curve [range=0.85–0.91] relative to blind expert-structured clinical assessment).

General Cognition

The MMSE

13 is a well-known and widely used test for screening cognitive impairment. Scores range from 0–30. Scores below 24 reflect cognitive impairment. CLOX: An Executive Clock-Drawing Task

15 is a two-part instrument designed to discriminate the executive control of clock-drawing from drawing per se. The patient is first instructed to draw a clock on a blank page (CLOX1). He or she is instructed only to “draw a clock that says 1:45. Set the hands and numbers on the face so that a child could read them.” Once the subject begins to draw, no further assistance is allowed. Then the examiner draws a clock and invites the subject to copy it (CLOX2). Both drawings are rated on the same 15-point scale (lower scores indicate greater impairment). Cutoff scores of 10/15 (CLOX1) and 12/15 (CLOX2) represent the 5th percentile for young adult control subjects.

CLOX1 is the most “executive” of six published clock-drawing tests.

19 CLOX1, but not CLOX2, is significantly associated with the level of care received by elderly retirees.

20 In contrast, CLOX2, but not CLOX1, is significantly associated with mortality.

21The Executive Interview (EXIT25)

12 provides a standardized executive control function assessment. It takes approximately 15 minutes to administer and has high interrater reliability (

r =0.90). It correlates well with other executive control function measures, including the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (r=0.54), Trail Making test part B (r=0.64), Lezak’s Tinker Toy test (r=0.57), and the Test of Sustained Attention (time, r=0.82; errors, r=0.83). A cutoff score of 15/50 is recommended to detect clinically significant executive control function impairment.

The EXIT25 is a strong independent predictor of cross-sectional level of care

22 and longitudinal change in instrumental activities of daily living

23 among elderly retirees. EXIT25 performance also predicts other clinically relevant outcome measures such as medication compliance and medical decision making capacity.

24 –

25 Analysis

Because of the small sample size, nonparametric statistics were used. Bivariate associations were tested by Kendall’s tau for continuous variables, and the Mann-Whitney U test for dichotomous variables. Sertraline’s effect was assessed relative to baseline for all outcome measures, using Wilcoxon matched-pairs test for dependent samples. Four end-points were considered: cognitive performance at visit 3 regardless of dosage, first follow-up on 150 mg of sertraline per day, cognitive performance at maximal tolerated sertraline dose, and best performance regardless of follow-up time or dosage. Clinically “meaningful” improvement was defined

a priori as a decline >3.0 EXIT25 points from baseline. “Remission” was defined as the achievement of an EXIT25 score <15/50 at any point in the trial. The sertraline effect size was estimated by Cohen’s

d (d=

M 1 −

M 2 /σ

pooled, where σ

pooled =√[(σ

1 2 + σ

2 2 )/2]) using baseline means versus cognitive performance on 150 mg/day, unless otherwise specified.

RESULTS

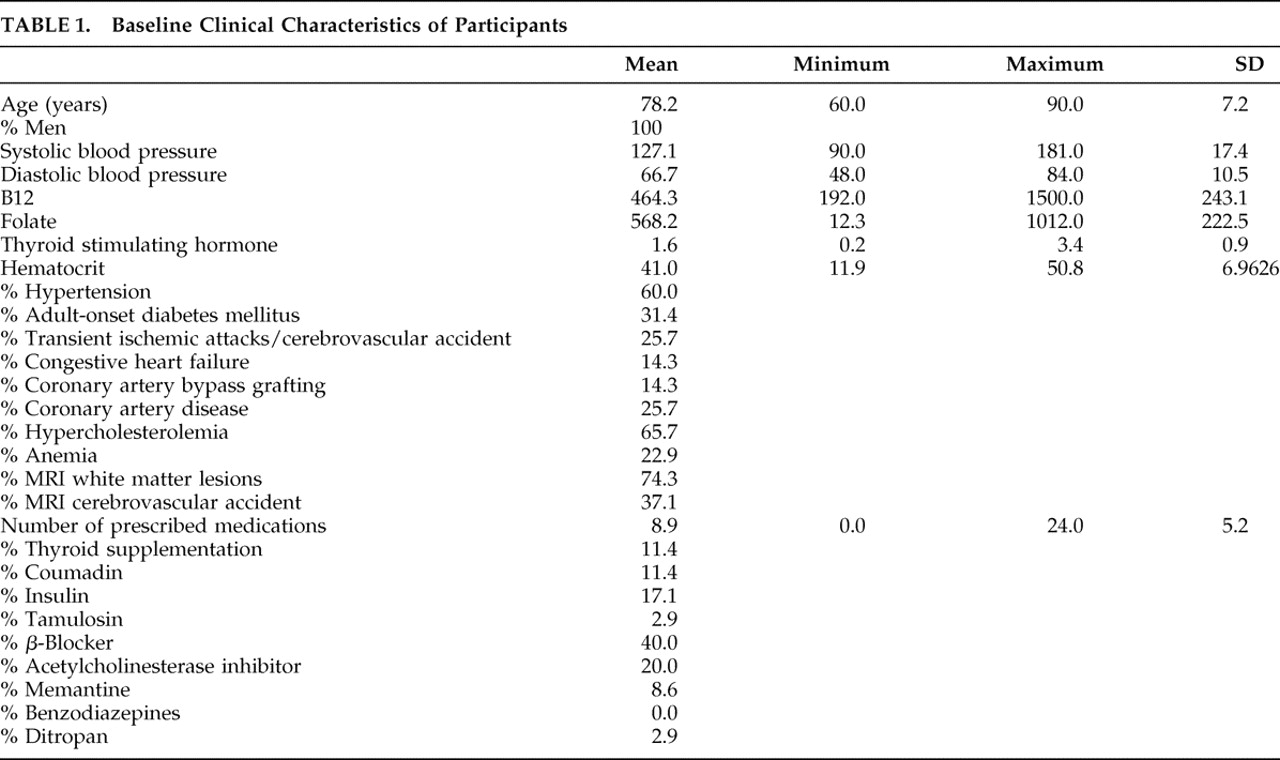

Baseline clinical characteristics are presented in

Table 1 . All the patients were male (mean age 78.2±7.2 years). There was a high prevalence of stroke risk factors (hypertension 60.0%; diabetes 31.4%; hypercholesterolemia 65.7%; documented transient ischemic attack/stroke 25.7%) and ischemic cerebrovascular disease confirmed by MRI (white matter lesions 74.3%; cortical and/or lacunar stroke 37.1%).

These were found in the context of comorbid medical conditions. On average, these patients were receiving 8.9±5.2 prescribed medications, including insulin (17.1%), thyroid supplements (11.4%), and beta-blockers (40.0%). Despite their objective cognitive impairments at baseline (88.3% failed the EXIT25 at 15/50; mean 22.0±5.3), relatively few participants were receiving psychotropics at the time of their referral (acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: 20.0%; memantine: 8.6%; benzodiazepines: 0%). These medications were withdrawn before sertraline monotherapy. Mean GDS scores (3.3±2.7) were within normal limits.

Hematocrit was moderately associated with CLOX1 (τ=0.50, p=0.01), EXIT25 (τ=−0.49, p=0.01), and MMSE (τ=0.44, p=0.01), and heart rate was associated with GDS score (τ=0.48, p=0.01), but no association survived Bonferroni’s correction. There were no other significant correlations between baseline cognitive measures and any other clinical descriptor, including age, serum B12, red blood cell folate, TSH, hematocrit, resting heart rate, systolic or diastolic blood pressure, or the number of prescribed medications (by Kendall’s tau; p>0.5 in all cases).

Twenty-six patients (74.3%) tolerated a sertraline dose >100 mg. Two (5.7%) received a maximum dose of 200 mg. The most common side effects were sleep disturbances (five patients, 14.3%) and motor symptoms (four patients, 11.4%). Two patients developed tics. One noticed a change in gait. One complained of tremors. Three patients (8.6%) experienced visual hallucinations, including hypnogogic. Only three patients (8.6%) experienced gastrointestinal side effects. All side effects resolved with dose reduction or sertraline’s discontinuation.

Seven patients (20.0%) discontinued sertraline because of side effects. Two patients developed diarrhea on ≤100 mg/day; one developed insomnia and diarrhea on 50 mg/day; one developed insomnia and a tremor on 50 mg/day. One patient developed insomnia and visual hallucinations on 100 mg/day; two developed visual hallucinations on 150 mg.

Table 2 presents baseline and outcome performance on each cognitive measure. The mean sertraline dose increased progressively from 75.0±30.3 mg/day at visit 1 to 135.3±46.0 mg/day at visit 3.

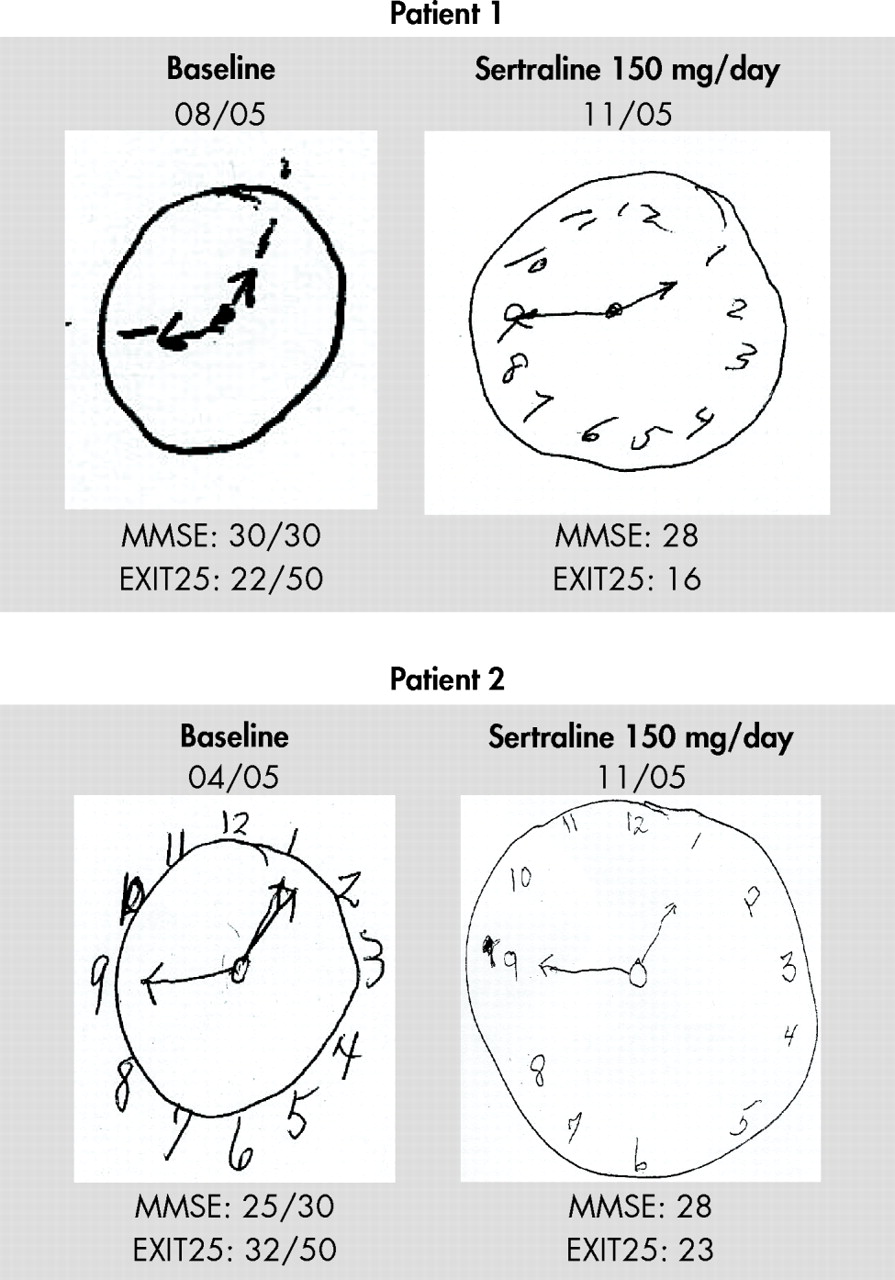

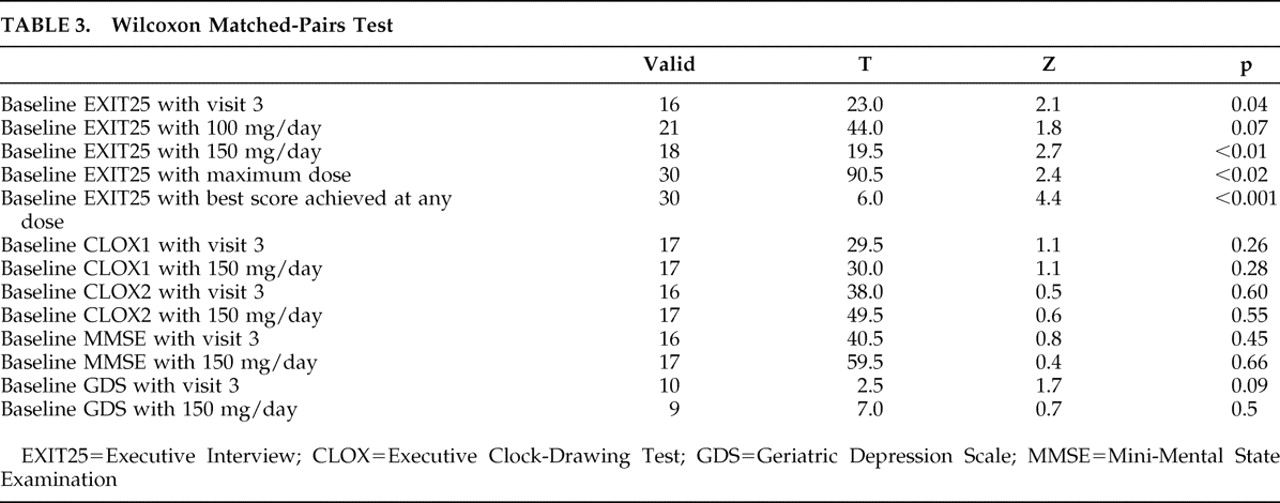

Only the EXIT25 demonstrated a significant improvement in response to sertraline (

Figure 1 and

Table 3 ). Sertraline had a significant effect on EXIT25 scores at visit 3 regardless of dosage, at first follow-up on 150 mg/day, at the maximum sertraline dose, and on best performance regardless of follow-up time or dosage. Sertraline had no significant effects on CLOX1, CLOX2, GDS, or MMSE scores at any endpoint.

The mean change in EXIT25 scores (baseline to first follow-up on 150 mg/day) was −7.4±6.2 points (d=0.89). The mean change in EXIT25 scores (baseline to best score at any dose) was −6.4±5.3 points (d=1.05). Overall, 20 patients (57.1%) experienced a clinically meaningful improvement in executive control function. Twelve patients (34.3%) achieved remission. The EXIT25 score worsened in only two patients exposed to sertraline.

DISCUSSION

These data suggest that sertraline may have both statistically significant and clinically meaningful effects on executive control function in cognitive impairment of dementia patients representing a subset of patients with vascular cognitive impairment. This analysis is limited by the small sample size, the retrospective design, open-label drug administration, and the lack of a control group. However, our ability to demonstrate a significant effect despite these limitations suggests a relatively large effect size (consistent with our estimate of d=0.89–1.05 for the EXIT25).

Sertraline’s effect appears to be specific for executive control function, as there were no comparable effects on the GDS, MMSE, or CLOX2. However, we may have been underpowered to detect an effect on these measures. Mean CLOX1 scores normalized on sertraline, but this effect was not significant.

That sertraline may have effects on executive control function as measured by the EXIT25 is particularly notable. First, the EXIT25 is a well-documented predictor of functional status, level of care, medication compliance, and decision-making capacity across a wide variety of conditions.

8 The EXIT25’s association with disability does not generalize to all putative executive measures and may be limited to a specific dimension of executive control function.

26 This factor can be shown to be co-labeled by measures such as the Wechsler Digit-Symbol Substitution task and verbal fluency, which have been previously shown to be sensitive to sertraline effects (

Table 4 ). Thus, sertraline may be specifically improving a dimension of executive control function that is particularly relevant to functional outcomes.

Second, the EXIT25 has been used in a variety of clinical trials, including two for vascular dementia in elderly outpatients. Both vascular dementia studies examined the effects of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors on the EXIT25. Aguilar et al.

27 found no significant effect of donepezil, 5 mg/day, on EXIT25 scores in 974 outpatients with “possible” or “probable” vascular dementia. In contrast, Auchus et al.

28 found a significant effect on EXIT25 scores (p=0.04) in 788 vascular dementia patients treated twice daily with 8 mg or 12 mg of galantamine versus placebo. As in this study, there was no significant effect on CLOX1. Given such large sample sizes, these findings suggest a relatively small and clinically ambiguous acetylcholinesterase inhibitors effect size on EXIT25 scores.

Because we do not have a control group, we cannot directly address the possibility of a learning effect, although the EXIT25’s excellent interrater reliability does not suggest one.

12,

29 Moreover, O’Shaughnnessy et al.

30 have used the EXIT25 in a placebo-controlled clinical trial of erythropoietin for chemotherapy related cognitive impairment. Their baseline mean in the placebo group (N=47) was 5.5 EXIT25 points (i.e., a much less executively impaired sample than the current one and thus more likely to display a learning effect). After 4 weeks of therapy, the mean change in EXIT25 scores in the placebo group was only 0.3±2.4. Similarly, the mean annualized change in EXIT25 scores among untreated nondemented elderly retirees is estimated at 0.89 points/yr.

31 Thus, EXIT25 scores are stable at short, intermediate, and long term time scales.

Although we do not measure functional status explicitly in the GEM MEM2, the changes in executive control function we observed in response to sertraline are likely to be clinically meaningful.

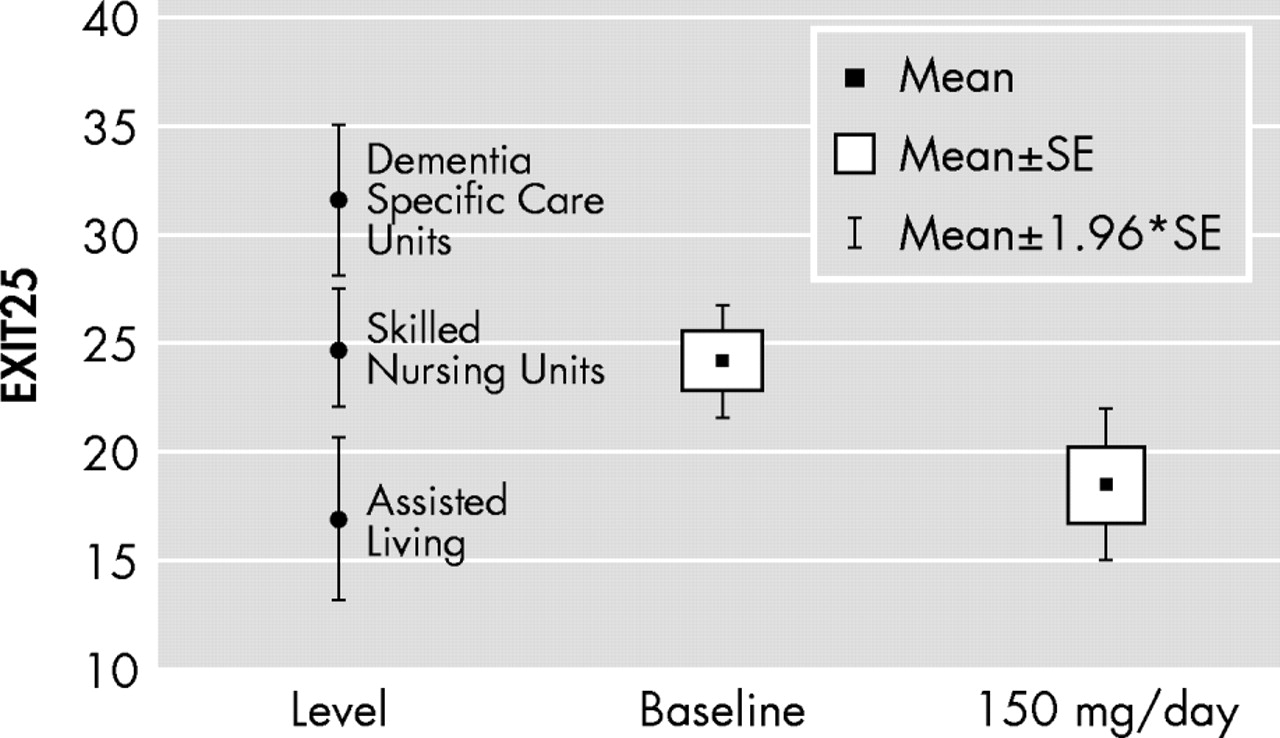

Figure 2 maps EXIT25 scores at baseline and on sertraline 150 mg/day relative to level of care-specific EXIT25 norms among comparably aged residents of a San Antonio retirement community. Longitudinal change in EXIT25 scores has been found to explain almost 40% of the variance in the rate of change in instrumental activities of daily living in such facilities.

23 In contrast, neither the MMSE nor memory measures contribute variance to multivariate models of instrumental activities of daily living, independently of EXIT25 scores.

23We do not use acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in GEM MEM2 and thus have relatively little experience with their potential to affect executive control function in the context of type 2 dementia. However, the relatively weak effects of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors on EXIT25 scores in previous studies of vascular dementia

27 –

28 do not necessarily militate against the use of these agents in type 2 ischemic cerebrovascular disease because they may partially reflect case selection biases.

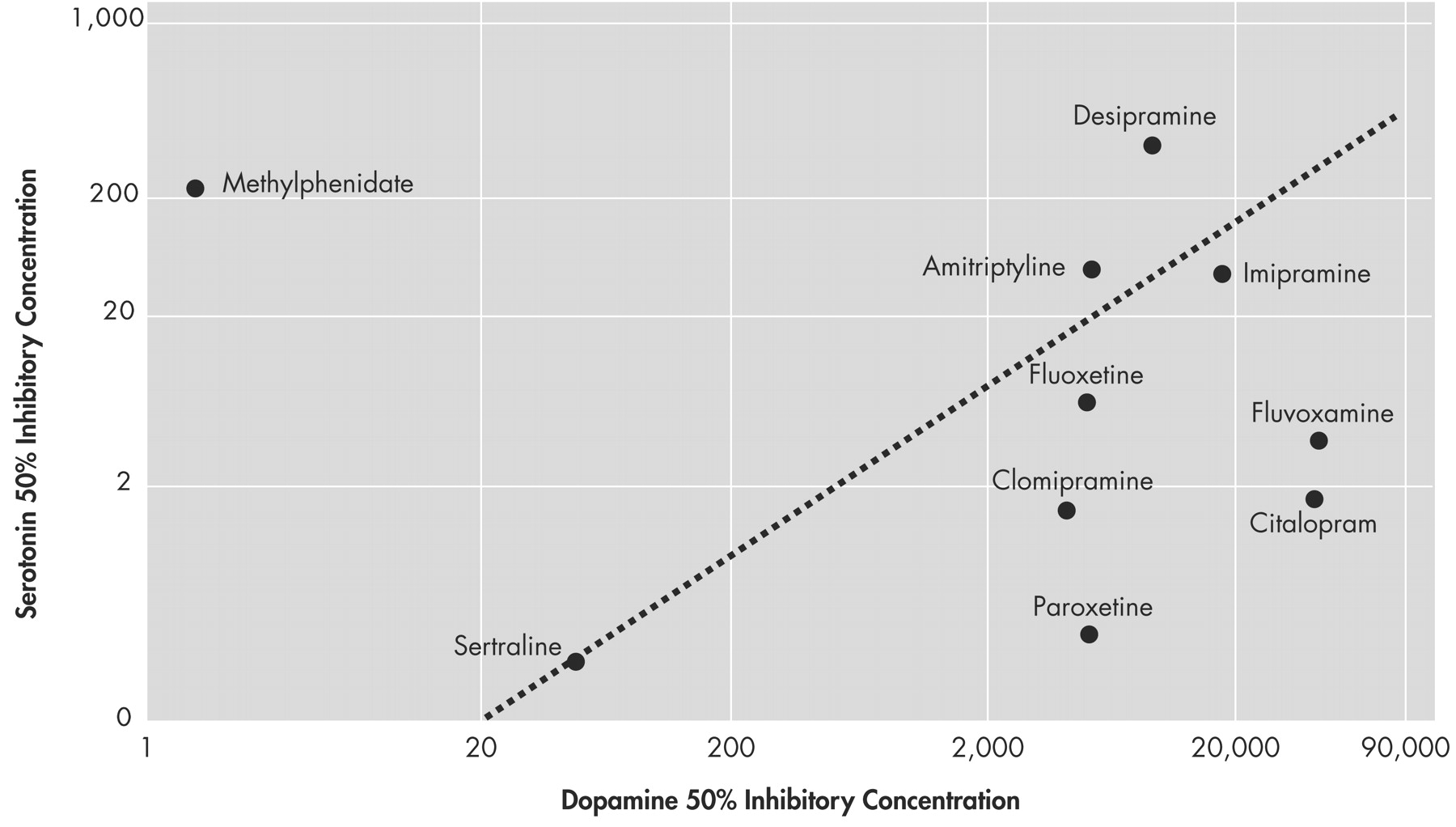

The current data do not address the mechanism by which sertraline can affect executive control function. However, a dopaminergic mechanism is suggested by the pattern of side effects we observed, which included sleep disturbances, tics and psychosis, but few gastrointestinal effects. Clinical data suggesting sertraline’s dopaminergic effects include preserved vigilance relative to other SSRIs and reports describing dopaminergic side effects such as tremors and tics.

32 –

35 Tatsumi et al.

36 determined in vitro equilibrium dissociation constants for 37 antidepressants and found that sertraline was the most potent at the human dopamine transporter (K

D =25±2 nM). Sertraline’s poor selectivity for dopamine relative to serotonin is comparable to tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline and imipramine rather than other SSRIs (

Figure 3 ).

37 –

38Finally, although we cannot dismiss an antidepressant effect without more rigorous data collection, the time required for sertraline’s effect on executive control function was often shorter than expected for an antidepressant effect, sometimes less than a week.

1Another recent study has examined the effect of antidepressant treatment on executive functioning after stroke.

39 As is our cases, executive function improved after antidepressant therapy, independently of depressive symptoms, and in the absence of a global change in cognition, as measured by the MMSE. Unlike our cases, improvement was not observed during active treatment, but was instead delayed after several months.

Both fluoxetine and nortriptyline were employed in that study.

Figure 3 suggests that these agents will differ significantly in their potency at dopamine reuptake sites, yet the delayed effects on executive control function were independent of the antidepressant employed. Thus, it may be mediated through some other mechanism. If the results of our experience can be replicated in a placebo-controlled trial, it would suggest that antidepressants may have broad effects on executive control function, at different time scales and perhaps by different mechanisms. These effects may extend beyond antidepressants’ narrow indication for mood disorder.