Hysterical Conversion/Somatization, Malingering, and Surveillance

In conversion disorder, according to APA,

9 the “somatic symptom represents a symbolic resolution of an unconscious psychological conflict” (page 494), obtaining or not a secondary gain through symptoms that “are not intentionally produced to obtain the benefits.” In conversion/somatization disorders, pseudoneurological symptoms are typically present.

5,

7,

9In contrast to hysterical conversion, malingering is a conscious feigning of illness and the purpose is overt.

27 It is a medical diagnosis but not a specific disease. Various clinical behaviors are particularly suspect of malingering,

9,

28 but psychological methods to detect deception are still not powerful enough.

29 Jones

30 writes, “It may be almost impossible for a court to conclude that the claimant is malingering without wholly convincing evidence, such as video observation of the claimant over a period of time.” Therefore surveillance is indispensable to assess whether an illness behavior may be a lie

12,

13,

31 and constitutes a historical resource in the realm of chronic pain diagnosis.

32 Malingering is under-recognized because it requires opportunistic and covert documentation of behaviors that refute veracity of the alleged symptoms.

33 Pain management physicians never recommend surveillance of pseudoneurological patients they label with CRPS I, and therefore only a minority of our CRPS I patients had been surveilled. When surveillance is incompatible with the reported or enacted disability, malingering is practically definite. False positives are inconceivable in nonmalingerers. Therefore the positive predictive power of surveillance must be very high,

34 but the method is bound to substantial false negatives by chance, or because the subject may be aware of surveillance.

Here we document that, among many other possible choices, malingerers may enact a fraudulent and fairly stereotyped clinical profile of immeasurable pain associated with elements from the limited natural inventory for illness expression in a limb, namely displayed weakness, abnormal movements, sensory loss, allodynia, hyperalgesia, and changes in the physical appearance of the segment. We emphasize that such clinical display amounts to subjective self-report or is susceptible to willful modulation or self-infliction. The objective physical changes can result just from disuse rather than from autonomic neuropathology.

18 This profile is often assessed concretely by the clinician as implying “neuropathic pain.”

Neuropathic Pain and CRPS I: Taxonomy and Hypothetical Mechanisms

“Neuropathic pain” is a debated clinical attribution reserved by some authors to characterize patients with structural (“tissue”) neuropathology,

2 and broadened by others to encompass patients exhibiting atypical neurological dysfunction without demonstrable neuropathophysiology, but with assumed peripheral or central hyperexcitability.

35,

36 Whereas it is no surprise that such a malleable profile may be simulated by malingerers, we remark that those who thus malinger invariably end up labeled as CRPS I because they do not carry a neuropathological lesion to qualify for CRPS II and, we argue, because the descriptive category CRPS I flexibly accommodates atypical “neuropathic” clinical profiles without testable physical bases. Refreshingly, the new redefinition implicitly excludes CRPS I from “neuropathic pain.”

3As a diagnostic concept, CRPS I is also debated. It is taken to reflect neurological dysfunction; its localization and pathology are “unknown,” and there is no diagnostic test. The task force on taxonomy of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) chose the following diagnostic criteria for CRPS I:

1. The presence of an initiating noxious event, or a cause for immobilization; 2. Continuing pain, allodynia, or hyperalgesia with which (sic) the pain is disproportionate to any inciting event; 3. Evidence at some time of edema, changes in skin blood flow, or abnormal sudomotor activity in the region of the pain.

Criterion 4, one that “must be satisfied,” reads: “This diagnosis is excluded by the existence of conditions that would otherwise account for the degree of pain and dysfunction.”

1 Thus, the label “CRPS I” is by default; a leftover nickname that lacks evidential medical power. It is assumed to be a syndrome, or even a discrete disease, when in fact it is a listing of nonspecific symptoms and signs awaiting differential diagnosis, which is traditionally bypassed.

37 –

39 Neurophysiological testing is wrongly dismissed as futile because it is predictably normal, even in the presence of displayed weakness, paralysis or sensory loss. In absence of differential diagnostic workup for these patients, management is abortive and only iatrogenic harm can follow.

37,

40,

41Hypothetical neuropathophysiological mechanisms are also controversial for CRPS I. For Max,

2 in CRPS I there is no neural

lesion and the evidence of neurological

dysfunction is precarious as it relies on self-reported allodynia, pain, and abnormal motion, unaccompanied by true clinical and physiological signs of functional impairment. Conversely, Merskey

36 argues that the clinical resemblance of CRPS I and CRPS II implies that both profiles are “neuropathic” and states that CRPS I reflects “a dysfunctional set of neurons.” In reality, the resemblance is shallow. CRPS I patients express atypical neurologically unexplainable symptoms, and there is no measurable biological evidence of neuronal dysfunction.

4 Humans and experimental animals with documented nerve pathology do not display these atypical clinical profiles.

4,

42 All there is for putative neural mechanisms behind CRPS I is an unverifiable claim of sensitization of second order neurons by nociceptor barrage, assumed by uncritical extrapolation to explain perpetuation and expansion of pseudoneurological symptoms.

43,

44The sympathetically maintained pain hypothesis can be dismissed on the grounds of negative current scientific medical evidence.

37,

45 In turn, the hypothesis that these patients harbor subclinical neuropathology of peripheral unmyelinated fibers is not supportable by reliable data. Indeed, evidence-based differential diagnosis was not implemented for the eight chronic pain patients labeled CRPS I (RSD) and studied histopathologically by van der Laan et al.

46 Several of them displayed atypical dystonia. The nerve and muscle samples were obtained from amputated legs with severe recurrent infections or chronic edema, and the authors concluded that there was “no consistent pathology in the peripheral nerves.” A reduced myelinated fiber density was partly attributed by the authors to endoneurial edema. The changes in unmyelinated fibers reported in four of the eight cases (median age 40.5 years) are explainable by aging alone.

47,

48 To their credit however, the Dutch authors correctly recognize that the concept of sympathetically maintained pain may be rejected as a placebo artifact and that the pathogenesis of RSD is unclear. Today, German authors argue against this peripheral hypothesis.

49,

50More than a few neurologists have regarded the clinical profile that many denominate RSD/CRPS I as potentially brain/mind driven.

20,

51,

52 Determination of psychogenic origin should not be based just upon absence of detectable physiological anomaly. It should be based upon demonstration of neurophysiological normality of self-reportedly disturbed, subjective sensory, or willfully drivable motor functions, but most importantly upon explicit detection of reputable

pseudoneurological phenomena that are assessed as

psychogenic by DSM-IV-TR and by learned authors.

5 –

7 In the case of many subjects labeled CRPS I, pseudoneurological phenomena include (a) fluctuating cutaneous hypoesthesia or hyperalgesia/allodynia, spreading or metastasizing beyond neural, radicular or segmental territories

4,

20,

24 ; (b) punctual verbal denial, while blindfolded, of every brief natural stimulus within a reportedly anesthetic area

15,

53,

54 ; (c) normal two-point discrimination of stimuli applied to areas of reportedly profound hypoesthesia; (d) hypoesthesia reversed by placebo

15 ; (e) muscle weakness with interrupted voluntary upper motor neuron drive, even in absence of inhibiting pain

14,

19,

23 ; (f) atypical abnormal movements or dystonia that are of sudden onset, distractible, entrainable, or relieved with placebo

21,

22,

25,

26 ; and (g) recovery of paralysis with placebo.

25The symptom

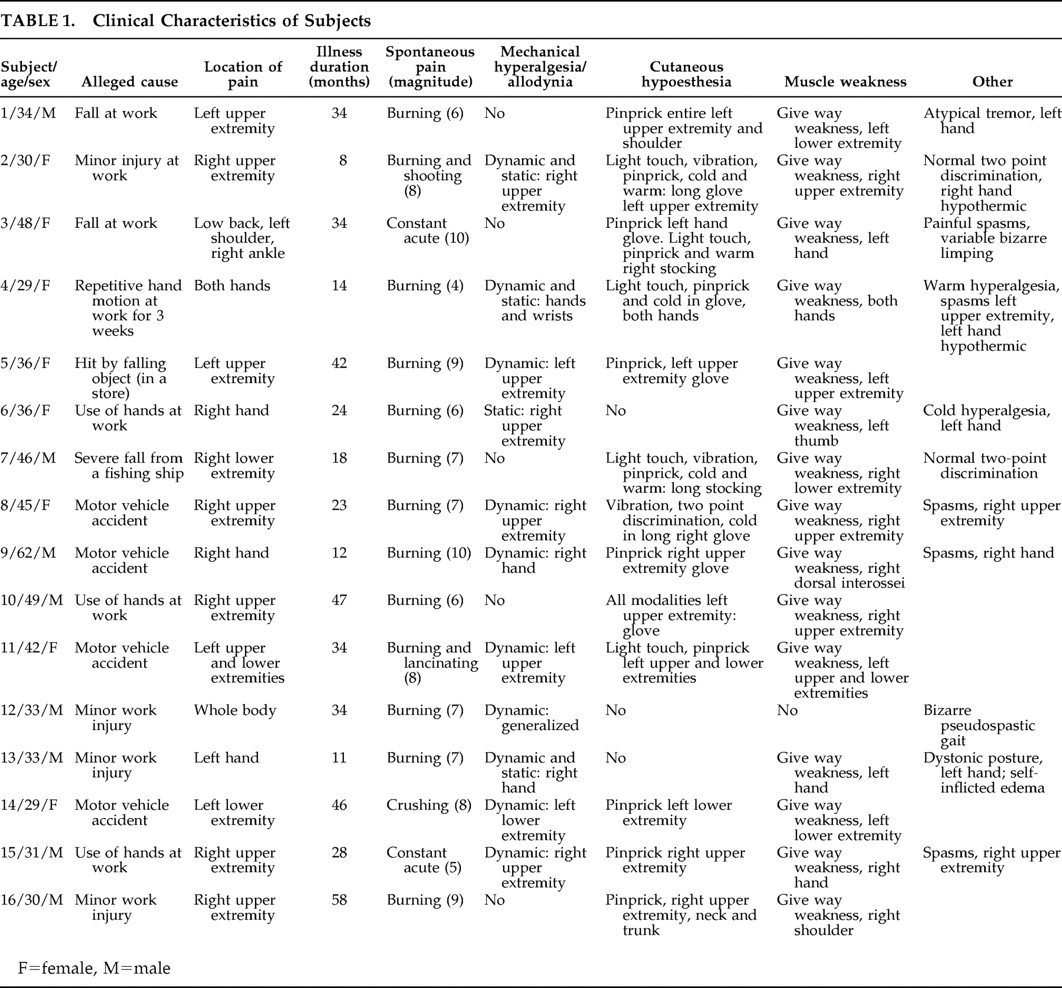

allodynia deserves special analysis in this context. The mechanical hyperalgesia prevailing in the present cohort of subjects was of dynamic type (

Table 1 ) and is known to be mediated by myelinated fibers,

17 which places such abnormal sensation in the category of

allodynia, a term coined to specify a pain induced by stimuli that do not normally elicit pain.

1 For Lindblom and Hansson

55 allodynia mediated by tactile myelinated fibers reflected CNS dysfunction, specifically sensitization of second order neurons within the spinal cord, a hypothesis still dominant among pain researchers.

43,

44,

56 It is often ignored that allodynia might also be a clinical manifestation of hysteria, as pointed out by Mitchell,

57 or may be malingered as described by Jones and Llewellyn,

32 and clearly shown in the present series of patients. We agree with Max

2 that, in and of itself, the symptom allodynia does not necessarily indicate structural lesions nor dysfunction of the nervous system.

CRPS I: Brain Component

A minority of patients provisionally labeled with CRPS I are shown to harbor unrecognized neuropathy.

58 Most “classic” CRPS I patients display what seems at first sight a neuropathologically based illness, but the profile is characteristically atypical and pseudoneurological as there is neither demonstrable peripheral nor central pathway pathology.

4,

59 This clinical profile reflects brain origin.

5,

7,

9,

54 Changes in the brain are increasingly recognized in CRPS II and CRPS I patients.

60 Indeed, functional imaging of the brain in patients with posttraumatic neuropathic, or postherpetic neuralgia, relative to healthy comparison subjects, shows decreased activity of the contralateral thalamus.

61 These are likely plastic changes evoked by abnormal afferent activity from injured primary sensory neurons. Using functional MRI in patients labeled CRPS I, Apkarian et al.

62 reported widespread prefrontal hyperactivity, increased anterior cingulate limbic activity and decreased activity of the contralateral thalamus. These changes might signal injury to primary sensory neurons in unrecognized neuropathy (thus, CRPS II). We believe that in CRPS I such changes are primary and are unlikely to reflect amplification of the nociceptor-induced “spinal cord changes that accompany chronic pain conditions.”

62 Effective placebo removes both symptoms and functional MRI anomalies.

62 In hysterical conversion with sensory loss, striatothalamocortical neuronal circuits with important limbic input, believed to modulate sensory decoding, are pathologically deactivated.

63 Moreover, in hysterical patients communicating chronic pain and sensory loss, the areas of abnormal brain activity are the same as those reported in CRPS I

64 and signify neuronal activation of the emotional limbic brain. Abnormal brain imaging does not necessarily signify neuropathology.

65CRPS I: Discrete Neurological Disease, Hysteria or Malingering?

All these malingerers fit IASP criteria for the label CRPS I.

1 It might be argued that by virtue of criterion 4, CRPS I is excluded because of the existence of a condition that accounts for the symptoms: malingering. Semantics aside, the undeniable existence of malingerers displaying what their physicians assessed as CRPS I proves that at least a subpopulation of CRPS I-labeled individuals are brain-driven cases of pseudoneurological illness behavior. Thus, it becomes mandatory to include both malingering and hysteria in the differential diagnosis of patients who fit the CRPS I menu because “the current IASP criteria for CRPS have inadequate specificity and are likely to lead to over diagnosis.”

66Shaw

67 reckoned malingering to be the cause of RSD, although he failed to distinguish feigning from unconscious hysterical somatization. Conversely, rejecting the potential deliberate psychogenic nature of CRPS I/RSD is equally biased and challenged by previous reports

4,

13,

28,

68 –

70 and by the present series of malingerers. Recently Mailis-Gagnon et al.

71 reported patients displaying the nonspecific profile of CRPS I, plus self-inflicted cutaneous stigmata, implying a gross personality disorder. Intriguingly, the authors acknowledge the patient’s factitious nature while stressing “the legitimacy of CRPS as a diagnosis.” The possibility that all CRPS I patients are malingerers is untenable given that many conversion/somatization-based unintentional pseudoneurological patients are truthful in the expression of their display.

72 On the other hand, malingerers might choose to amplify symptoms of a neuropathologically based condition legitimately, causing spontaneous pain and associated sensory and motor manifestations, but in the present series all subjects displayed CRPS I with only neurologically unexplained symptoms.

40,

72 Besides, as per surveillance, we only included

pure malingerers 73 who feigned the entire symptom complex rather than just exaggerating

bona fide symptoms.

74 Moreover, malingerers may amplify an unconscious, psychogenic, pseudoneuropathic painful syndrome since malingering is often concomitant with conversion/somatization.

75,

76 This satisfies the concept that conversion/somatization involves self-deception while malingering is deception of others.

77 Using functional MRI, Spence et al.

78 observed that in healthy people who intentionally deceive there is activation of the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, which for Spence et al.

78 may be engaged in generating lies or withholding the truth. It is striking that cortical areas activated in conversion/somatization

79 are similar to areas activated in conscious deception. Thus, coexistence of conversion/somatization and feigned symptoms is in keeping with neuronal data.

We conclude that “neuropathic pain patients” classified in the provisional CRPS I category, who in reality may harbor an undiagnosed nerve injury (CRPS II) or unconscious hysterical conversion, alternatively or concomitantly may very well be malingerers. Unconscious conversion/somatization is a legitimate health disorder with no room for pejoratives. However, mistaking pseudoneurological displays, of one kind or another, for neuropathologically based disease fosters iatrogenesis by commission and by omission

51,

80 –

83 and rewards those who feign. We have all missed more than one malingerer in our clinics.

5,

84,

85