D espite a dramatic increase in American Indian life expectancy in recent years,

1 remarkably little is known about the nature and frequency of cognitive impairment among older American Indians.

2 Although a few studies have examined the utility of standard neuropsychological testing in this population,

3 –

5 little is known about the performance on common neurocognitive screening measures among American Indian elders. This gap is especially noteworthy since American Indians have high rates of several conditions that increase risk for poor cognitive functioning, such as alcohol abuse and addiction,

6 –

8 diabetes,

9,

10 traumatic brain injury,

11,

12 and overweight/obesity and cardiovascular disease.

13,

14 Further, American Indians are disproportionately poor (28.4% compared with 12.4% of the U.S. general population),

15 and low socioeconomic status has been linked to several factors that might affect cognitive ability. These include pre- and postnatal complications, malnutrition, exposure to environmental toxins, increased risk of head injury, and risky health behaviors.

16,

17 This constellation of factors suggests that American Indians may be at considerable risk for the development of cognitive disorders associated with aging. As the population of older American Indians continues to increase, so does the need to develop methods by which to identify cognitive impairment and its optimal assessment in this population.

American Indians, Dementia Prevalence, and Cognitive Testing

A handful of small, non-population-based, empirical studies have examined dementia among American Indian and Canadian First Nations people.

3 –

5,

18 –

24 Overall, most studies of cognitive test performance to date typically have shown little difference between Native and non-Native samples, although most of these investigations have been conducted with relatively acculturated tribes,

3 –

5,

22,

25 some of whom also have relatively low levels of genetic American Indian heritage.

21 This is important because acculturation status may affect elders’ performance on cognitive tests.

26An earlier investigation by this research team

27 examined older American Indians’ scores on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)

28 and the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale—Second Edition (DRS-2)

29,

30 compared with age- and education-adjusted norms developed with 18,000 community-dwelling participants (age 18–85+ years) in the NIMH Epidemiological Catchment Area Program survey.

31 For the purpose of that investigation, possible cognitive impairment was defined as performance greater than 2 standard deviations below the mean of each participant’s corresponding age- and education-matched cohort. Utilizing this criterion, 10.9% of the sample had possible cognitive impairment. For the DRS-2, no large-scale, population-representative norms were available, so the most demographically comparable published norms available were employed. These were age-adjusted norms derived from 36 European American and 53 African American urban norms

32 with fairly similar age and education levels (mean age=74 years [SD=5.9], range=62–95; mean education=10.5 years [SD=3.6]).

32 Again employing the criterion of performance greater than two standard deviations below the mean of each participant’s DRS-2 score to an age-matched cohort to define possible impairment, 27.4% of elders had possible cognitive impairment. Gender was significantly associated with performance on both tests and education with the DRS-2, the latter finding accounted for by the lack of education adjustments in the Vangel & Lichtenberg 1995 norms. The article concluded that the examination of the possible effects of ethnicity, socioeconomic status, type/character of education, and language on MMSE and DRS-2 performance is essential in understanding cognitive test performance and developing culturally appropriate norms.

27Factors Associated With Performance on the MMSE and DRS-2

A number of factors are related to performance on cognitive measures. Age,

32,

33 education,

32,

34,

35 and language

17 are well-known contributors to differential performance on such measures, whether directly, in combination, or reflecting the influence of other variables for which age, education, and language serve as proxies. The effects of ethnicity/race also contribute to performance differences on cognitive measures, although the extent of their contribution is variable.

36 Socioeconomic status has been found to affect performance on the MMSE.

37 Ethnic minorities generally score lower on many cognitive tests, even after correcting for years of education and socioeconomic status.

38 While no definitive explanations can be found for these disparities, possible contributors include lower quality educational experiences

38 and associated socioeconomic deprivations (e.g., poor nutrition, inadequate health care, etc.) that contribute to poorer cognitive health.

36With this in mind, our work examines performance on the MMSE and the DRS-2 in a community-dwelling American Indian sample. The goal was to investigate the predictors of differential performance on these assessment instruments in this culturally unique population, since it is likely that performance reflects factors other than neurocognitive disease alone. It was hypothesized that several variables, including health factors (e.g., alcohol problems, stroke, head injuries); language proficiency (both English and tribal language); education; boarding school history; indicators of economic need; ethnic identity; age; gender; and blood quantum would be predictive of performance on the two cognitive measures.

RESULTS

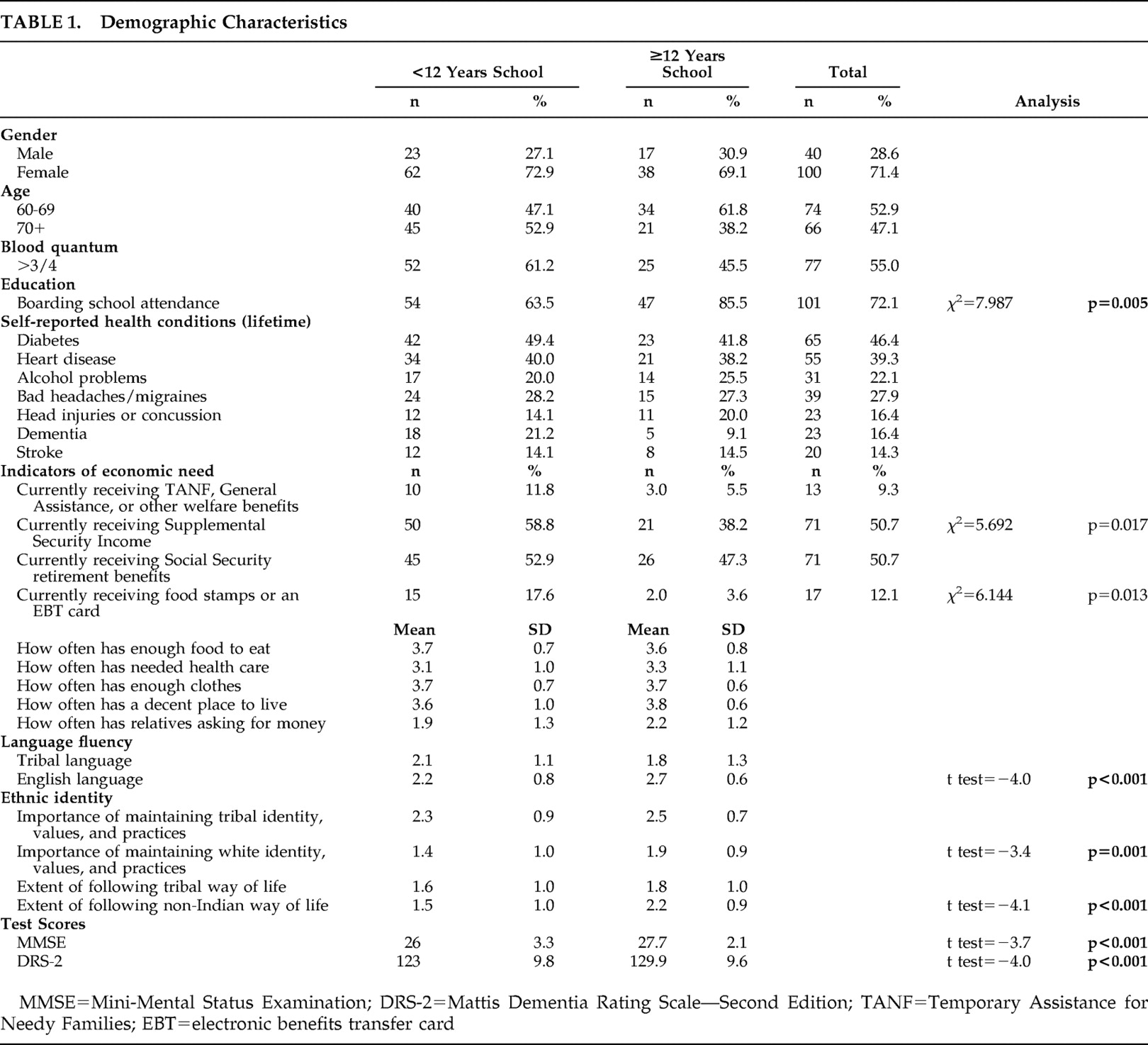

MMSE scores ranged from 16 to 30, while DRS-2 scores ranged from 93 to 143. Approximately 93% of both male and female participants had MMSE scores between 21 and 30. Sample characteristics comparing those with less than or equal to and more than 12 years of education are summarized in

Table 1 .

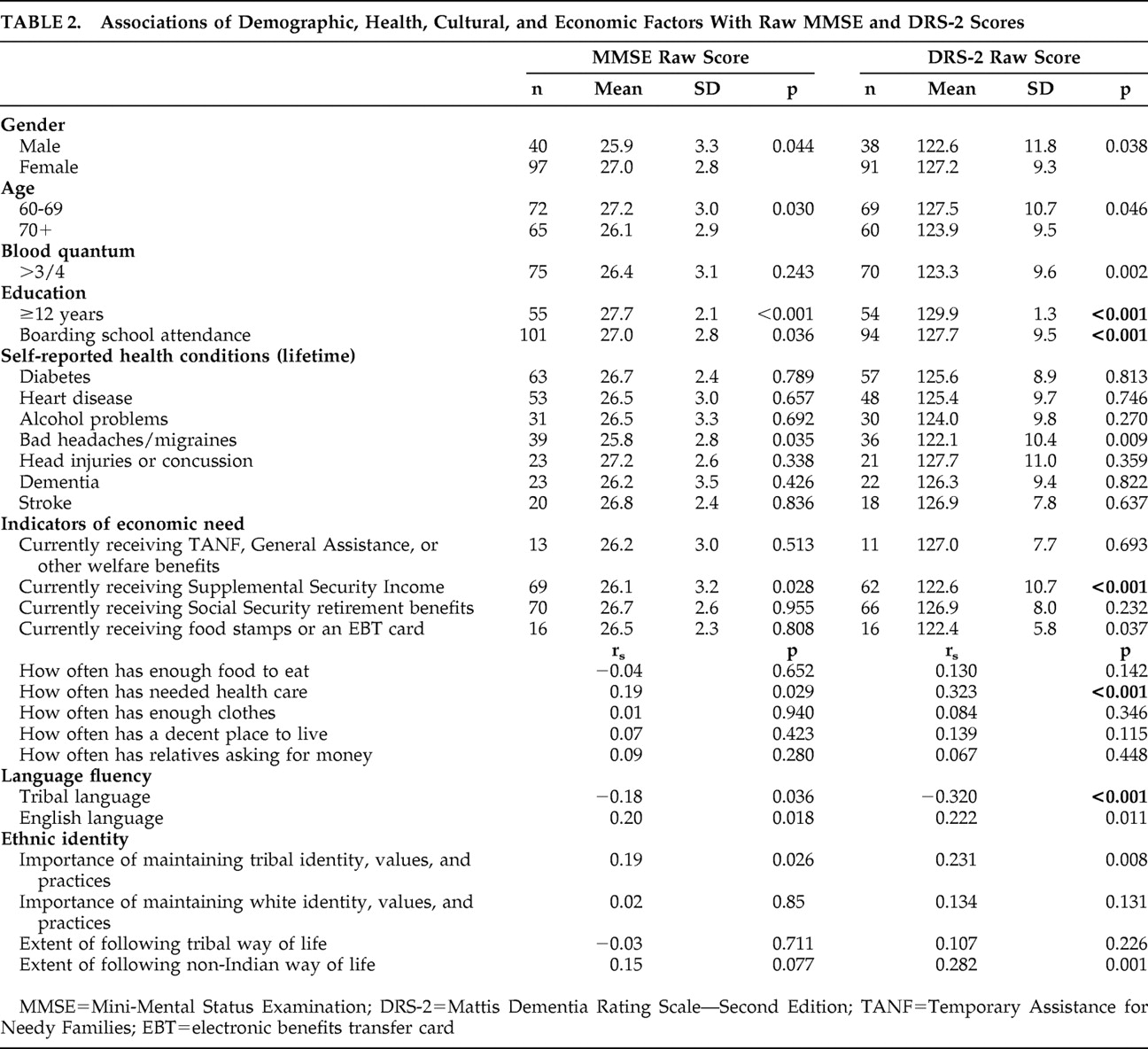

Results demonstrating variables that were individually associated with higher MMSE and DRS-2 scores using t tests and correlations are presented in

Table 2 .

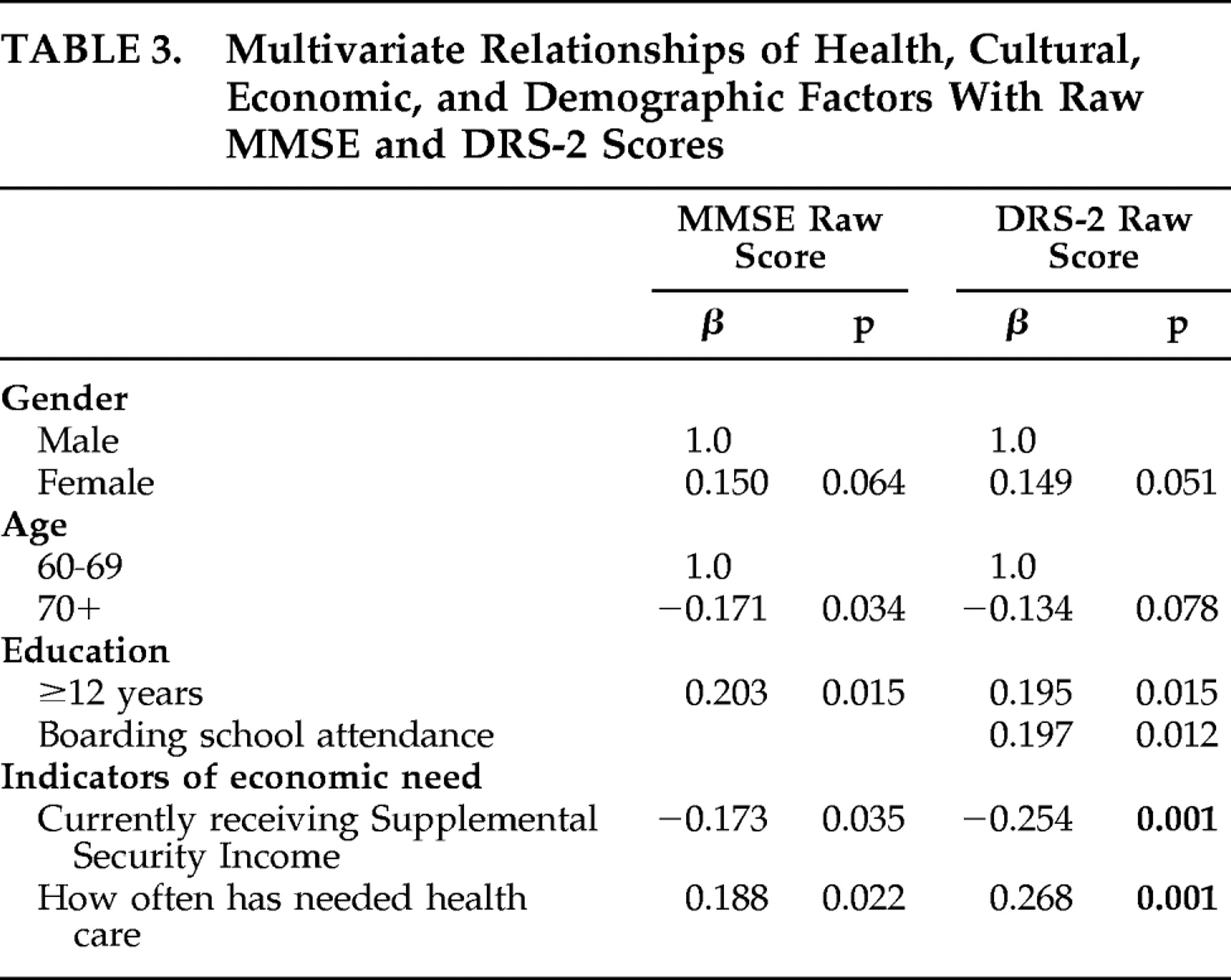

In a multivariate model for the MMSE (after controlling for gender and age), being younger, reporting 12 or more years of education, not receiving Supplemental Security Income, and often having needed health care predicted higher MMSE scores (

Table 3 ). In the DRS-2 multivariate model (after controlling for gender and age), reporting 12 or more years of education, having attended boarding school, not receiving Supplemental Security Income, and often having needed health care predicted higher scores. No significant interactions were identified.

As several culture-related variables were individually associated with higher MMSE and DRS-2 scores but were not significant in the multivariate model, we ran additional analyses to look at the interrelationships of the independent variables to assist in explaining these findings. English proficiency’s univariate relationship to higher MMSE and DRS-2 scores was explained by 12 or more years of school (mean English proficiency =2.71 [SD=0.59] for those with 12 or more years of school compared with mean=2.21 [SD=0.78] for those with 11 or fewer years; t test=−4.23, p<0.001). English proficiency’s univariate relationship to higher DRS-2 scores was explained by a history of attending boarding school (mean English proficiency =2.56 [SD=0.65] among those attending boarding school compared with mean=2.00 [SD=0.86] for those who did not; t test=−3.71, p<0.001). The extent of following the non-Indian way of life’s univariate relationship to higher MMSE and DRS-2 scores was explained by 12 or more years of education (mean non-Indian way of life =2.20 [SD=0.87] for those with 12 or more years of education compared with mean=1.54 [SD=1.00] for those with 11 or fewer years; t test=−4.11, p<0.001). Finally, reporting less than or equal to three-fourths blood quantum’s univariate relationship to higher DRS-2 scores was explained by often having needed health care (mean having needed health care =3.37 [SD=0.86] for those with less than or equal to three-fourths blood quantum compared with mean=3.00 [SD=1.12] for those with greater than three-fourths blood quantum; t test=2.11, p=0.036).

DISCUSSION

In general, education and indicators of economic need predicted higher scores on both the MMSE and DRS-2 in this sample of American Indian elders. Having more formal education was related to better performance on both the MMSE and the DRS-2; in addition, younger age was related to better performance on the MMSE. Age and education have been found to be associated with better performance in previous studies of these measures in other populations.

31,

32,

37,

45 –

47 Additionally, boarding school attendance was related to higher scores on the DRS-2. Since to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine this measure in an American Indian group, it is not clear why those who attended boarding school performed better on the DRS-2, although it is possible that the acculturative aspect of the boarding school experience may have played a role in some way, perhaps by providing a heuristic framework that made it easier for boarding schools attendees to complete measure-specific assessment tasks that reflected a Western, biomedical conceptualization of cognition.

It is worth noting the complex relationship between performance on the cognitive tests, the educational variables, English proficiency, adherence to a non-Indian way of life, and blood quantum. In particular, we found an association between English proficiency and MMSE and DRS-2 scores, although both of these relationships were explained by the 12 or more years of education variable. Those who reported 12 or more years of school were more likely to report greater English proficiency. In addition, we found an association between English language and the DRS-2 scores, which was explained by a history of boarding school attendance. Those who reported a history of boarding school were more likely to report greater English proficiency. It is not clear why this finding occurred with the DRS-2 score only. We found an association between the extent of following the non-Indian way of life and MMSE and DRS-2 scores—again both of these relationships were explained by the 12 or more years of education variable. Finally, we found an association with blood quantum and the DRS-2 score, which was explained by often having needed health care.

Those who reported more frequently receiving needed health care had better scores on both the MMSE and DRS-2. Here it is important to note that rudimentary health care through the Indian Health Service is supposed to be universally available to American Indians on this reservation, although in reality the system is chronically underfunded and struggles to keep up with demand.

48 It follows that those who were able to negotiate their way through this system and receive the care they needed may have been advantaged in other ways as well, including better cognitive health and/or test-taking ability.

The relationship between nonreceipt of Supplemental Security Income and higher MMSE and DRS-2 scores is not surprising given the level of impoverishment of recipients of these benefits. For instance, an individual is prohibited from having more than $2,000 in resources (e.g., cash, bank accounts, land, life insurance, personal property, and vehicle) in order to qualify for the program.

42 Supplemental Security Income recipients may therefore be disadvantaged in a number of ways that might impact their cognitive functioning and/or test-taking aptitude or ability, including early nutrition, educational opportunities, and parental involvement in early education efforts.

Of the seven health variables examined here, bad headaches/migraines was the only health-related variable that was significant at the univariate level. However, this variable dropped out of the final multivariate regression models. That health problems emerged as nonsignificant may reflect the inadequacies of a self-report method of ascertaining their presence/absence. Further, the lack of significance of gender here is striking and is in contrast to our earlier work which used normative data rather than raw scores;

27 however, this finding is consistent with that of others.

31,

32,

49 Likewise, we did not find an effect of blood quantum in this study, which is consistent with some studies’ findings of the nonsignificance of race on the DRS-2 in samples of whites and African Americans.

32,

50This study has several limitations, one of the most obvious being its focus on one tribe and its use of a purposive sample drawn from senior nutrition program sites. Although these nutrition program sites are believed by many community members to be more universally utilized in reservation settings than comparable programs that serve the general population, the possibility exists that unique characteristics of this sample limit generalizations to the larger American Indian population. Also, socioeconomic status was not assessed comprehensively but was instead evaluated via indicators of economic need. In addition, we were unable to explore possible relationships between gender and ethnic identity, language fluency, and self-reported health conditions. While potentially interesting, such additional analyses are beyond the scope of this study yet are worthy of future investigation. Lastly, this research did not include a clinical neuropsychiatric examination as a source of external validation of neurological (including cognitive), psychiatric, and general health status; accordingly, potentially informative clinical characteristics of study participants may be opaque to detection in the present study and hence not entered into the regression models predicting MMSE and DRS-2 scores in this sample.

Despite these limitations, the present findings suggest that educational factors and economic resources are related to performance on the MMSE and DRS-2 among older American Indians. Such factors must be considered when selecting these measures, and by extension other assessments of cognitive performance, for use and interpretation in these populations.