To the Editor: In our study, we evaluated thyroid functioning and its behavioral correlates in children diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorders (ADHD) and ADHD comorbid with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). Beyond suggesting the role of thyroid hormones on ADHD, our study also indicated an association between thyroid hormone concentrations and several symptoms of disruptive behavior disorder.

It has been already shown that thyroid hormone concentrations can have profound effects on neurocognitive development in the newborn.

1 This was suggested by studies revealing that the normal development of the monoaminergic and cholinergic neurotransmitter systems are not only thyroid-dependent but may also play an important role in the development of attention deficits and hyperactivity in animals.

2 In contrast to previous preclinical studies, human studies suggesting such a relationship between the thyroid hormones and ADHD are still controversial.

3 In light of evidence suggesting the developmental etiology of ADHD, and recently proven effects of abnormal thyroid hormone levels on brain development and cognition,

4 we aimed to evaluate the relationship between the hormonal function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis and the behavioral problems and attention-deficit symptoms of ADHD.

The study included children between the ages of 6 and 11 years (mean [SD] age: ADHD: 8.19 [1.27] years; ADHD + ODD: 8.06 [1.06] years; control group: 8.47 [1.31] years) who were diagnosed as ADHD and ADHD comorbid with oppositional defiant disorder (ADHD + ODD) according to the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. The ADHD, ADHD + ODD, and the control group included 21, 26, and 27 male subjects, respectively. We used the CBCL (Child Behavior Check List) to obtain standardized parental reports of children's problem behaviors. A 10-cc blood sample was taken from every child in the morning between 8:15 A.M. and 9:00 A.M., and plasma free T3, T4, and TSH levels were investigated with Immulite-2000 Apparat (Diagnostic Products Corporation, Los Angeles, CA) after the samples were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 3,000 rpm. There were no significant differences between the ADHD, ADHD + ODD, and the control group in terms of average age, IQ, sociodemographic data, and comorbid LD (p>0.05).

Interestingly, TSH levels in ADHD (2.82 [1.10] UI/ml) and ADHD + ODD (3.18 [1.13] UI/ml) group were

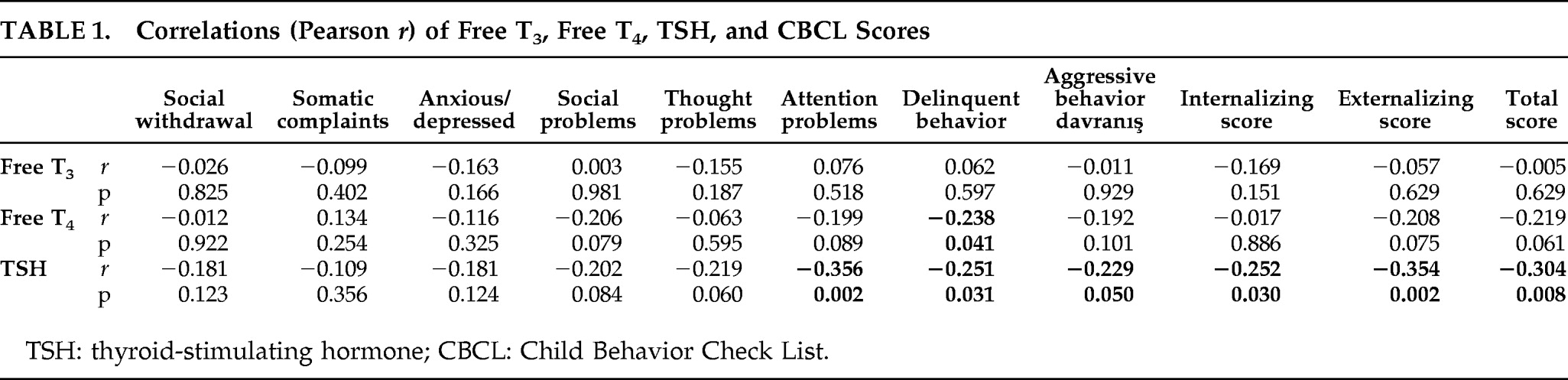

significantly lower as compared with the control group (3.59 [1.63] UI/ml; p=0.001; Kruskal-Wallis Test). However, although the TSH levels were not significantly different (p>0.05) between the ADHD and ADHD + ODD groups, they were significantly negatively correlated with CBCL ratings of behavioral parameters (

Table 1). Free T

4 levels were significantly negative, correlating only with CBCL ratings of delinquent behavior (r = –0.238; p=0.041; Pearson correlation;

Table 1).

Discussion

An interesting finding of this study is that the TSH levels were not only significantly lower in ADHD and ADHD + ODD groups, but also significantly negatively correlated with the severity of behavioral symptoms indicating that thyroid function may play also an important role in the development of ODD. Stein and Weiss

5 revealed that the children with ADHD–PI (Predominantly Inattentive type) were more likely to possess low FreeT4 levels, although the TSH levels were found not to be correlated with any cognitive or behavioral measures. It is difficult to determine what exactly caused the difference between our results and previous studies regarding the behavioral effects of FreeT4, Free T3, and TSH. However, getting more information about the function of the hormone-specific neuromediators and their possible interaction with the limbic system would help us to illuminate this hormone-related discrepancy.