Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), with a lifetime prevalence of 2.5% to 4%,

1 is one of the most prevalent and disabling psychiatric disorders. It is characterized by obsessions (which cause marked anxiety or distress) and/or compulsions (which serve to neutralize anxiety). Neurological soft signs (NSS), in contrast to hard neurological signs, are subtle neurological and nonlocalizing anomalies, including altered motor coordination, balance, motor integration, and sensory integration. NSS may reflect cerebral dysfunction in distributed neural networks, and they can give additional information on the functional organization that characterizes some psychiatric disorders.

2 NSS have been described in several psychiatric disorders, but they are particularly prevalent in schizophrenia.

3 Only a few studies have explored NSS in patients with OCD, and their results are contradictory. There is only one previous study, by Bolton et al.,

4 that compared NSS (assessed with the Cambridge Neurological Inventory) in patients with OCD and patients with schizophrenia and control subjects. In this study, as compared with patients with schizophrenia, patients with OCD had lower levels of neurological signs, including motor coordination soft-signs, tardive dyskinesia, catatonic signs, and extrapyramidal signs, and identical levels of NSS in other subscales (sensory integration, primitive reflexes, failure of suppression). This study has never been replicated. Other studies compared patients with schizophrenia with or without OCD and healthy controls.

5–7 Once again, the results are contradictory.

Sevincok et al., in 2004,

5 found that patients with OCD-schizophrenia had significantly higher NSS scores, restricted to sensory-integration items, as compared with controls. However, the same team, 2 years later (Sevincok et al. [2006]

6 and Poyurovsky et al. [2007]

7) did not find any significant differences in NSS between patients with schizophrenia with or without OCD. However, the number of OCD patients was low in these studies (N <25). Finally, studies examining NSS in patients with OCD, versus controls, also found contradictory results. Some of these studies found a higher prevalence of NSS in OCD patients than in healthy controls,

4,8 with impaired motor coordination and visuospatial tasks,

9 abnormal involuntary movements,

9,10 sensory-integration abnormalities, and motor overflow.

11 However, other studies did not report such differences,

7,12,13 and, overall, the studies remain inconclusive because of intrinsic limitations; these observations were done in rather small samples,

5–7 with no or insufficient information on medication status or history,

2–4,14–16 or extrapyramidal symptom assessment,

8,12,13,17 and/or without a standardized examination.

17,18 making any comparison difficult. It has been suggested that NSS in OCD patients may be used as an early element of diagnosis

4,19 or as predictors of good treatment response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

20 or response to psychotherapy,

21,22 but, here, as well, there are contradictory findings.

13,17,22,23 Overall, although some reviews state that NSS are increased in OCD, a closer reading of previous studies reveals that the picture is not very clear.

These investigations suggest that NSS may be higher in patients with early age at onset of OCD than in patients with later age at onset. However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has directly examined the influence of age at onset on NSS in patients with OCD.

Our primary objective in this study was to examine NSS in patients with OCD as compared with patients with schizophrenia and a control group. A secondary objective was to look at whether OCD patients with an early age at onset (before age 13) have more NSS than other OCD patients or the control group, and less than patients with schizophrenia.

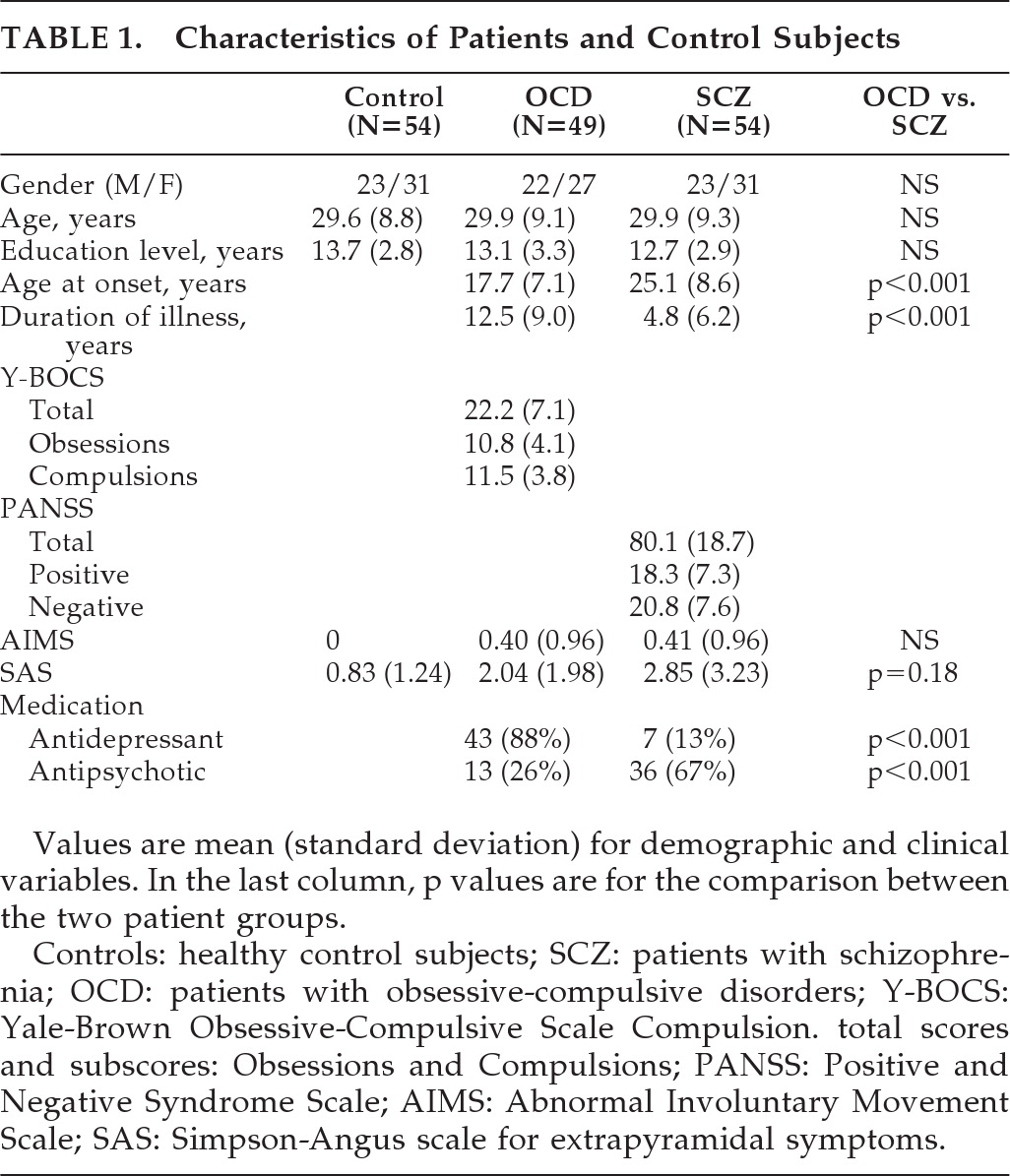

DISCUSSION

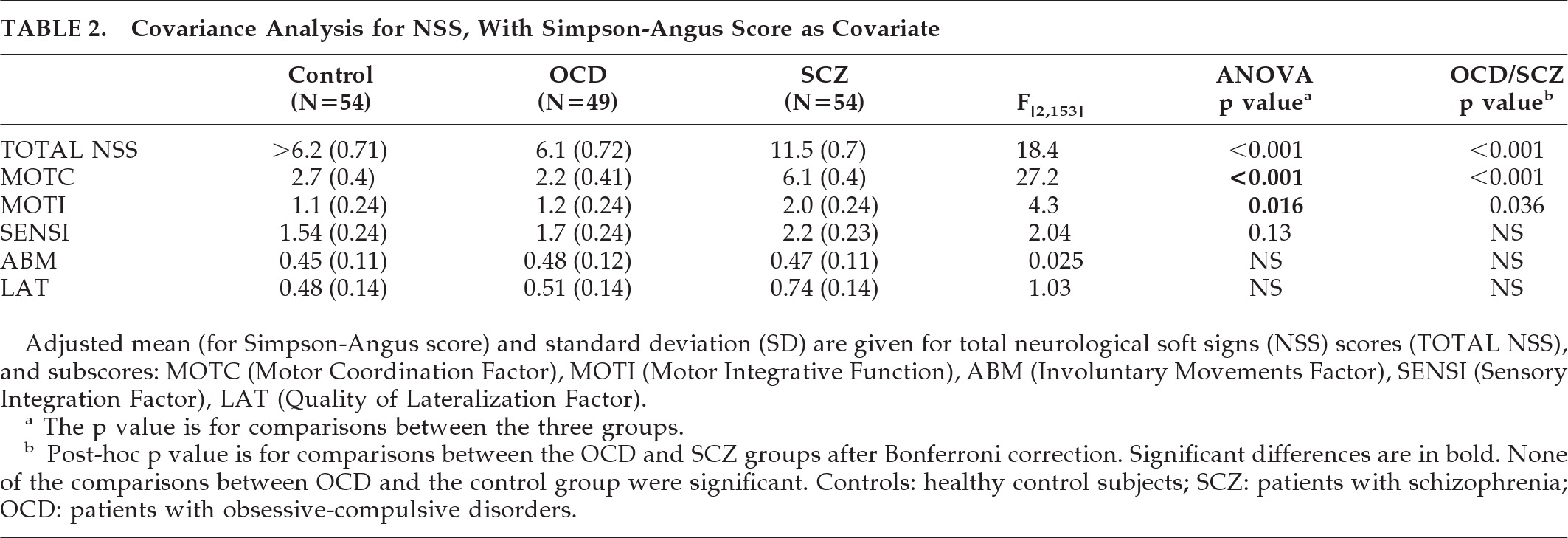

Both OCD and schizophrenia are thought to reflect abnormal brain development, and NSSs have been demonstrated to be a valid marker of abnormal neurodevelopment in patients with schizophrenia. The main aim of this study was to examine whether NSS could also be a valid marker of deviant neurodevelopment in patients with OCD. We compared OCD patients with carefully-matched patients with schizophrenia and controls and found higher NSS scores in patients with schizophrenia than in those with OCD, which did not differ from controls. Furthermore, we found no differences in the NSS total scores or subscores in patients with early- versus late-onset OCD (age <13 versus ≥13). Taken together, our findings do not support the idea that NSS indicate neurodevelopmental brain anomalies associated with OCD and suggest that NSS could be more specific to the neurodevelopmental anomalies associated with schizophrenia.

Our work has several features. First, the sample size was larger or similar to those of previous reports. Second, the inclusion criteria were very strictly defined, and the populations were well-matched. The two patient groups were well contrasted by excluding OCD in patients with schizophrenia (in contrast to others studies

5–7) and, conversely, psychotic symptoms in patients with OCD. These diagnoses were done on the basis of lifespan structured interviews based on DSM-IV criteria, which were used in some,

4–10,12,13 but not all

2,18 previous reports. Possible confounding factors were avoided by excluding, in particular, neurological disorders and substance abuse, information that is available in some,

4–7,12 but not all studies.

13,17,22 We also carefully matched the three groups on age and gender. Third, patients were carefully tested, by use of a validated, standardized examination, in contrast to some,

2,17,18 but not all

9,13,20,22 previous reports. Notably, this comprises semiquantitative rather than presence/absence ratings of NSS and could thus be more accurate, but could also lead to some differences from previous studies.

5–7,12 Fourth, the two groups of patients included patients naive for antipsychotic medication, including patients with schizophrenia, which was not the case in previous reports.

4–6,9,12,17 Also, we took into account the extrapyramidal status of the patients. In contrast with previous reports,

12,17 all subjects were examined not only for NSS, but also for involuntary movements and parkinsonism (using the well-validated AIMS

35 and SAS

36 scales, respectively). Because differences were observed between the two patient groups for parkinsonism, as measured by SAS, we adjusted the comparison SAS scores. We also made the decision to exclude patients with tics, who may constitute a specific group with regard to neurological condition and possibly underlying pathobiology. In previous studies, it is unclear whether patients with tics were included.

4–9,12,13,17,20,22,37Several limitations to this study should nevertheless be discussed. First, the sample size remained relatively small, despite being larger than in previous studies, and we cannot exclude a lack of power to detect differences, especially when subgrouping the patients with regard to their age at onset. Also, we were not able to analyze separately the patients with tics, although they appear to have specific neurological features. Second, the later age at onset and shorter duration of illness of patients with schizophrenia could potentially bias the results in favor of finding higher NSS scores in OCD patients. Moreover, as would be expected, the groups were different with respect to psychotropic administration. To assess the effects of medication on NSS, it was impossible to introduce, in a linear-regression analysis, either chlorpromazine-equivalents, because most of OCD patients were not under antipsychotic medication, or SSRI dose-equivalents, because most patients with schizophrenia did not take antidepressant medication, and, of course, controls were not taking any medication. However, the relationship between treatment effect and psychotropic NSS remains controversial.

8 Also, when we compared patients with versus without antipsychotic and with versus without antidepressant, we did not see any significant differences. These are consistent with several other studies that found no influence of medication on NSS in OCD patients.

5,17 or in patients with schizophrenia.

14–16 Moreover, Hollander et al.

8 report that NSSs were more common in medication-free patients with OCD than in controls. Last, the patients were not necessarily representative of all patients with OCD or schizophrenia. Although consecutively encountered, OCD patients were also selected for European Caucasian descent, and patients with schizophrenia were additionally selected by age- and gender-matching with OCD patients.

Keeping in mind these limitations,

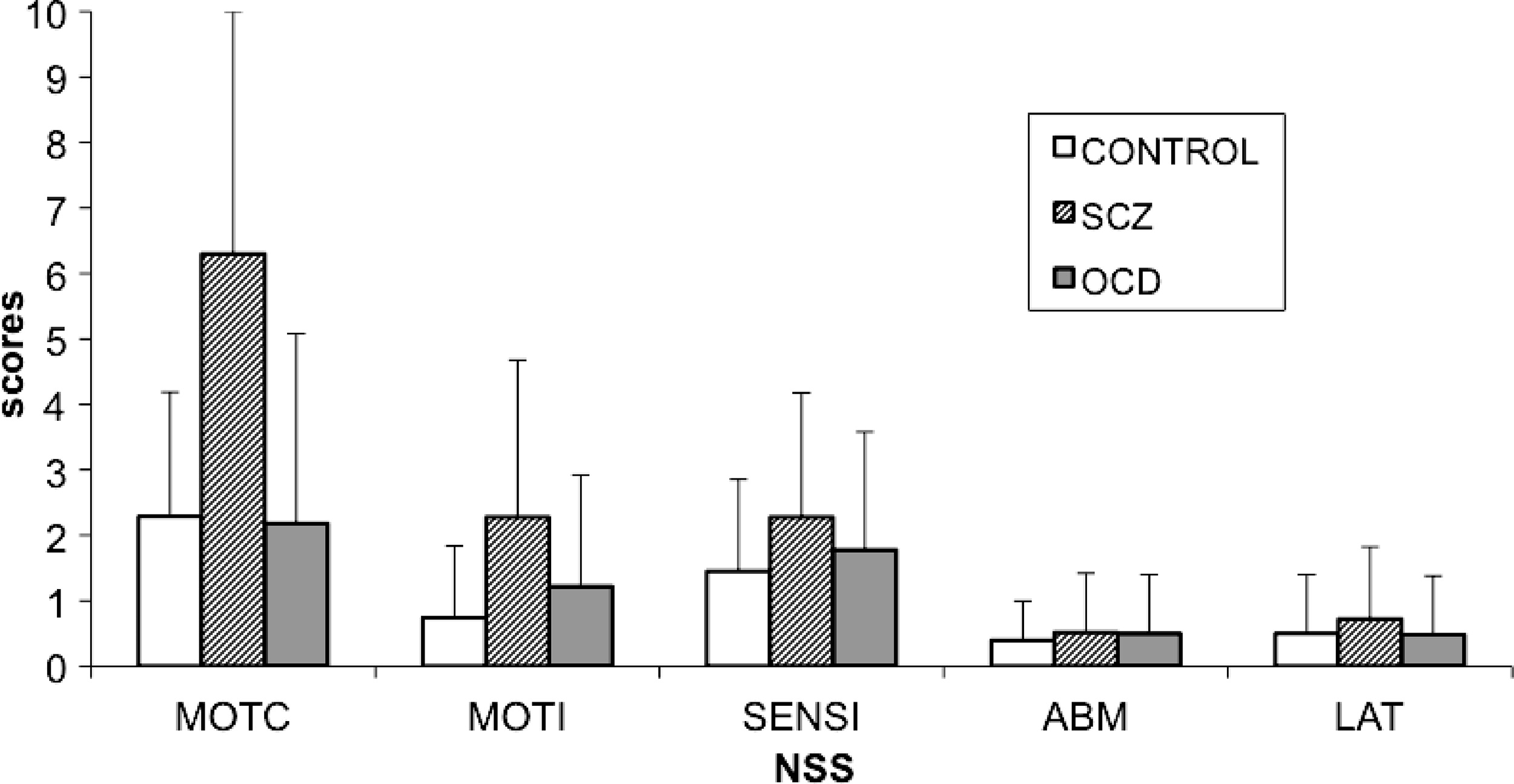

4–6,10,17 we did not replicate previous findings of an increase in NSS in OCD patients as compared with controls and rather found significantly lower NSS scores in those patients than in patients with schizophrenia. Patients with OCD had significantly lower total scores and motor coordination subscores than patients with schizophrenia (

Figure 1). Our results are in line with the Bolton's study

4 with a larger sample size that compared OCD patients (N=50) to patients with schizophrenia and reported fewer NSS signs, less motor-coordination impairment, tardive dyskinesia, and “extrapyramidal signs” (i.e., parkinsonism) in OCD, including increased tone in limbs, decreased associated movements in walking, shuffling gait, arm-dropping, tremor, or neck rigidity in OCD patients than in patients with schizophrenia. Also in line with their observations, we did not observe any significant difference between the OCD group and the schizophrenia group in terms of sensory integration, involuntary movements, or quality of lateralization.

Our results suggest that the NSS we assessed in this study are more severe in patients with schizophrenia than in OCD patients; furthermore, we found no differences when comparing patients with OCD to healthy controls. Our results are in line with two others studies in which no differences in terms of NSS between patients with OCD and controls were found.

12,13 However, two studies found neurological abnormalities in patients with OCD.

4,8 In one of them, the authors

8 found more NSS in OCD than in the control group, including impairments in fine motor coordination and visuospatial functions and also involuntary and mirror movements. In the other one, Bolton et al.

4 found that OCD patients had higher NSS scores than the control group in motor coordination, sensory integration, and primitive reflexes, but also more extrapyramidal signs and deficient suppression. We did not replicate those findings. Differences in medication status could partly explain these contradictory findings. In Bolton's study, 60% of patients (versus 26% in our study) were on medication,

4 with no further details on the type of medication. Noteworthy, although OCD patients had higher parkinsonism scores than controls, comparisons of NSS were not adjusted for this difference.

4 In Hollander's study, patients were medication-free for at least 2 weeks (with no further details on the mean duration of withdrawal and or the type of medication). This rather short duration of withdrawal could be too limited to avoid residual neurological side effects induced by antidepressants and even more by antipsychotics.

8Several lines of evidence suggest that early age at onset of OCD could be associated with more brain anomalies.

28–30 Nevertheless, to our knowledge, there has been no other study examining the relationship between NSS and age at onset in OCD. Two different definitions of age at onset can be found in the literature: 1) the age at which symptoms were first noticed by the individual and/or family member;

28 2) the first time that symptoms altered functioning.

29 In this study, we chose to use the former definition, since it is likely to reflect the beginning of the disorder, whereas the latter defines the onset of the syndrome and, as such, reflects the severity of the symptoms.

We found no differences in NSS scores between EO-OCD and LO-OCD groups or between EO-OCD and healthy subjects, even when adjusting for age at time of assessment (data not shown). Furthermore, no correlations were found between the severity of NSS and demographic variables such as educational level or severity of disease in the OCD group. These results are in line with several other studies,

6,12,37,38 although one study has reported a positive correlation between the severity of obsession and high levels of NSS.

9 However, they did not find any correlation between severity of disease (Y-BOCS score total) and NSS.

Although NSS reflect dysconnectivity in distributed networks, involving fronto-thalamo-cerebellar loops,

39 the prevailing hypothesis regarding OCD suggests hyperactivity in the orbito-frontal cortex,

29,40 medial caudate nucleus, thalamus, and anterior cingulate gyrus, with no argument supporting dysconnectivity.

To conclude, NSS as assessed by the current scales, comprising items that discriminate patients with schizophrenia from controls, appear to be relatively specific to schizophrenia, whereas other neurological “subtle signs,” not present in these scales, could be worth exploring in OCD patients, in particular those assessing the frontal-striatal loops. Further studies are needed to explore neurological features of OCD in more depth, using other neurological “soft” or “hard” signs and extrapyramidal symptoms, and with a closer look at the subgroup of OCD patients with tics.

Acknowledgments

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

We thank all the patients and healthy volunteers involved.

This work was supported by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (Inserm), Centre Hospitalier Sainte Anne Hôpital Sainte-Anne and by the Fondation Pierre Deniker. The study was conceptualized by the principal investigator (MOK), and the funding source had no influence on the design or analysis of the study.

This study was promoted by Inserm and received financial support from the Fondation Pierre Deniker. In Paris, the study was conducted in the CERC, Centre d′Évaluation et de Recherche Clinique with the help of Narjes Bendjemaa, Françoise Polides, Souhail Bannour, and Marie-Josée Dos Santos.

The study was supported by the Collaborative Network for Family Study in Psychiatry (“Réseau d′étude familiale en Psychiatry”, REFAPSY) and by the Fondation Pierre Deniker, and coordinated by Pr. M.O. Krebs, Hôpital Sainte-Anne, Paris SHU: Pr. M.O. Krebs; SM 13,: Dr. M.N. Vacheron; SM 17,: Dr. F. Petitjean; SM 18: Dr. B. Garnier; CMME, Paris; Pr. J. Guelfi; CH Les Mureaux; Dr. G. Naruse; C.H. Guillaume Régnier, Rennes; Pr. S. Tordjman, Pr. B. Millet; C.H. Erasme Anthony; Dr. J.C. Pascal; C.H. Ville Evrard, Saint-Denis; Dr. D. Januel, Dr. L. Stamatiadis; C.H.U. Strasbourg; Pr. J.M. Danion; Hôpital Sud, Grenoble; Pr. T. Bougerol, Dr. M. Polosan; Hôpital Laborit, Poitiers; Pr. J.L. Senon, Dr. N. Jaafari, M.E. C. Turque; C.H.U. Bretonneau, Tours; Dr. F. Bonnet-Brilhault; Pr. C. Barthélémy; Fondation Lenval, Nice; Pr. F. Askenazy.

We also acknowledge Afsaneh Gray for the English editing of the paper.

Authors Jaafari and Baup contributed equally to this work.