“Lynn” is a middle-aged woman living on the streets in Pittsburgh—if “living” means sleeping naked on cold, rainy nights under a storefront awning in a working-class neighborhood.

Lynn, who is infested with scabies, is rarely sober and may have bipolar disorder, but because of her constant inebriation, it is difficult to be certain. She engages in high-risk sexual and drug-using behaviors. In her lifetime, Lynn has never been involved in lasting treatment, and no shelter or substance abuse facility within three counties will take her. Staff from the Neighborhood Living Project (NLP) are not deterred, however, and have worked doggedly to get Lynn off the streets and into a much-needed treatment regimen.

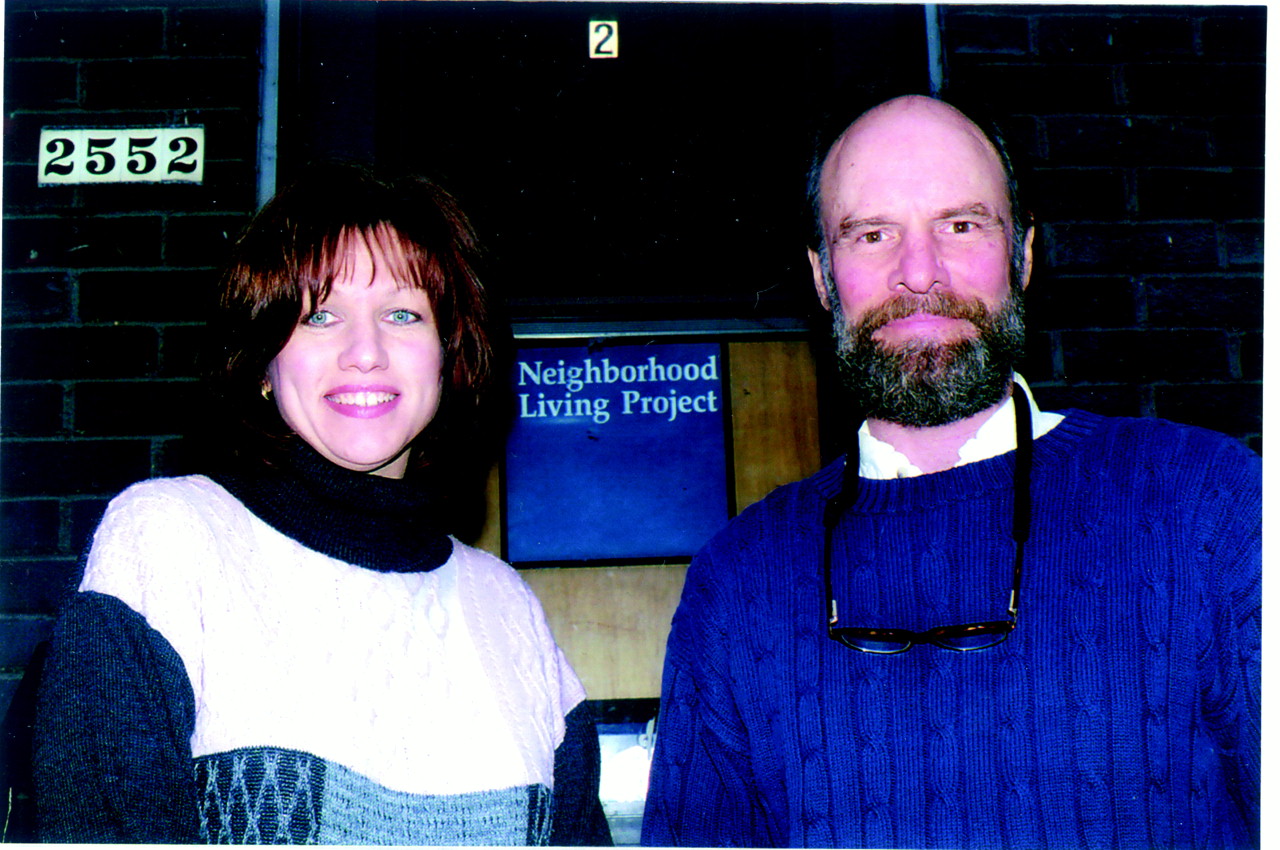

NLP, established in July 1999, provides a vast range of services to homeless individuals and families affected by mental illness. Funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the program is part of the Community Services and Training Department of Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic in Pittsburgh. The program, staffed by seven case managers, three psychiatric nurses, and one psychiatrist, seeks to provide clinical services, case management, supported housing, and respite to clients who have a sporadic history of treatment and are not currently in the treatment system.

About 70 percent of the clients have both a mental disorder and a substance abuse disorder. Referrals to NLP come from several different sources—mental health agencies, hospitals, and other clients. A few of the NLP clients are self-referrals. There are about five referrals a week, and 142 people are now in the program.

The program uses dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) in its treatment approach and offers DBT groups for clients in its main facility. Marsha Linehan, Ph.D., pioneered DBT in the early 1990s and used it to treat people with borderline personality disorder. According to NLP supervisor Diane Johnson, R.N., B.S.N., DBT is useful because it places a great deal of emphasis on the reciprocal relationship and collaborative work with the client, employing validation and problem solving.

“Eighty percent of the clients who were living in the streets or shelters at the time of their referral to NLP were in more stable housing after six months of services,” Johnson told Psychiatric News.

According to Johnson, funding sets priorities for the program’s objectives. “Because our funding comes from HUD, we have to focus on getting people into housing.” The goal of the housing track is to get clients off the streets and into some type of housing—whether it is short-term respite housing or an independent living situation, according to Johnson. The project maintains two respite apartments at NLP headquarters, which is located in a brown brick building in one of Pittsburgh’s less safe residential neighborhoods. When a client is ready for more permanent, independent housing, he or she pinpoints a desired living area within Allegheny County, and a NLP case worker will help the client find a suitable apartment there. The client spends 30 percent of his or her income on rent, and NLP subsidizes the rest of the rent for a two-year period. As long as the client is in NLP-supported housing, he or she should be committed to his or her recovery in some way—this may mean a recovery program for some, and mental health services for others, according to the NLP supervisor.

Said Johnson, “Although many of our clients never make it into independent apartments, we are committed to finding the appropriate level of housing for the client, such as a community residential rehab or a personal care home.”

The outreach track preceded NLP by a decade but is now an integral part of the program, according to Johnson. “The clients in the outreach track get as much service as those in the housing track, and we are just as committed to their well-being.”

When NLP identifies a client for the outreach track, one of its nurses conducts an on-site assessment wherever the client may be—on the streets, in a hospital, or in a shelter. Once the nurse determines what level of treatment the client needs, action is taken. The client may need to be placed in a shelter if he or she is on the streets or in some type of day program in which medications and other mental health services are available.

Usually, there is no coercion associated with NLP services, but where safety issues are concerned, it may be necessary, said Johnson. “This may mean committing someone to a hospital because he or she is a danger to himself or herself or to others, or getting someone off the streets and into a shelter because he or she may die of exposure.”

The first priority for NLP staff when assessing a new client is to determine whether there are any life-threatening behaviors, and if there are, to help the client to stop them. The second is to assess the client for treatment-threatening behaviors, such as consuming alcohol or taking illicit drugs.

The NLP staff assumes all responsibility for a client’s progress. “If the client is not doing well in treatment,” emphasized Johnson, “the onus falls on us—we never blame the client.”

“I’ve been homeless the majority of my life,” said Larry, who is the NLP receptionist and wanted Psychiatric News to publish his real name. Larry took his first drink at the age of 10 and has lived with alcoholism and major depression with psychosis into his adulthood.

“Finally,” said Larry, “in March of 1999, I hit bottom, and I had nothing left. I can only describe it as the cellar of hell.”

Larry soon entered a detox program, and when he entered an inpatient rehabilitation program run by the Salvation Army, NLP staff came to evaluate him. Upon his release, his NLP case manager and nurse found him mental health and rehabilitative treatment and helped him obtain medical help for another illness, newly diagnosed hepatitis C.

Said Larry, “The first medical treatments for the hepatitis were difficult for me because they carried a side effect of depression, which was one thing I definitely did not need more of.”

NLP staff were very supportive of him not only throughout the medical treatments, but also through his continued mental health and addiction treatment, according to Larry. Eventually, the staff placed him in the respite apartments and helped him to find his own apartment. Since staff thought that he would make a valuable addition to their staff, he became the NLP receptionist.

“Soon, my NLP subsidy will be stopping, and my case will be closed,” said Larry. He has some anxiety about this, but knows that he can turn to his new coworkers for help anytime. Larry, who will be the first point of contact for many people in need, added, “The silver lining to all of this is that I can help someone else by working here.”

At last mention, Lynn, who consistently failed to meet her caseworker at a designated spot downtown, had been committed to an inpatient psychiatric ward—much to the relief of NLP staff. Inpatient cognitive testing revealed below average intellectual functioning.

NLP staff continues to work with Lynn’s inpatient treatment team to find extended treatment for her. “We are confident that one day Lynn will receive all of the services that she needs,” said Johnson. ▪