This is one in a series of articles on psychiatrists who provided professional help to people affected by the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon last month. Links to additional news stories related to the terrorist attacks in this issue appear at the end of the article.

Tuesday, September 11, began like any other day in Manhattan for psychiatrists at St. Vincent’s Hospital. But within minutes, everything changed.

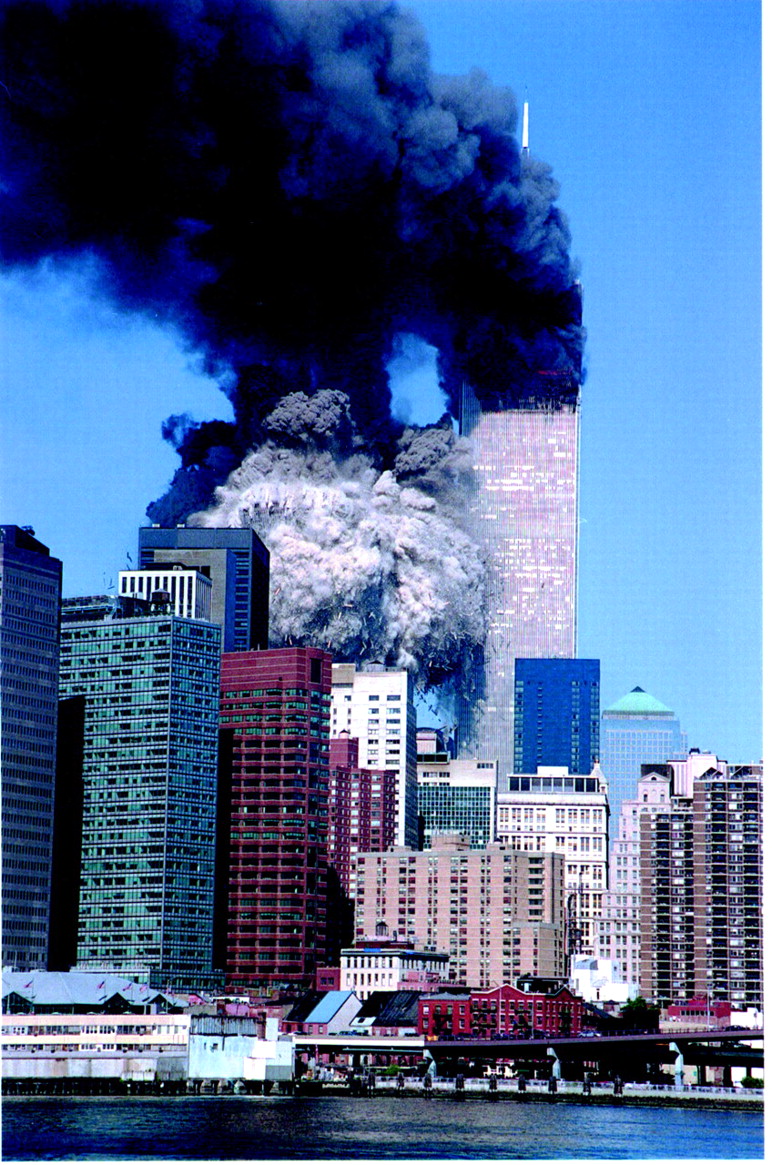

8:48 a.m.: The first hijacked American Airlines passenger jet crashes into the north tower of the World Trade Center.

8:50 a.m.: St. Vincent’s Hospital in lower Manhattan, which operates the trauma center closest to the World Trade Center, is notified of the crash and immediately mobilizes.

8:55 a.m.: Brian Ladds, M.D., walks outside the hospital to look at the World Trade Center buildings to decide whether he should reschedule his 9 a.m. appointment with a patient. Ladds is director of the psychiatric residency training program at St. Vincent’s Hospital.

“What I saw was a massive, disastrous fire consuming the upper floors of the north tower. I was stunned because we thought it was a small fire. A few minutes later—9:03 a.m.—I saw the second plane pass overhead and crash into the south tower, which then burst into flames,” Ladds told Psychiatric News. “I rescheduled my patient.”

9: 10 a.m.: St. Vincent’s staff anticipates receiving thousands of victims given the estimated 15,000 people working in the two towers. CNN estimated that 50,000 people worked in all seven buildings that make up the World Trade Center.

Physicians, residents, medical students, and other health professionals line the hallway from the emergency room to the cafeteria/lounge area to help, said Ladds, who is also associate chair for education and training in the department of psychiatry at New York Medical College. The college is affiliated with St. Vincent Catholic Medical Centers (SVCMC), which operates eight hospitals in New York including Manhattan.

Approximately 9:45 a.m.: The first casualties begin arriving in ambulances at St. Vincent’s Hospital.

10 a.m.: The south tower collapses, followed by the north tower at 10:28 a.m.

“During the next four hours, we began to notice that far fewer patients were coming through our doors than we expected. We began to consider the possibility that many did not survive,” said Ladds.

2:30 p.m.: St. Vincent’s decides to focus on providing information and support to families, coworkers, and friends of missing victims. Due to the overwhelming need, a family support center is set up at a nearby school campus and staffed by St. Vincent’s general hospital and psychiatric clinicians and volunteers from the New York City area.

The clinicians, mainly psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, and social workers, worked around the clock, some for 36 hours straight, said Spencer Eth, M.D., medical director of behavioral health services at SVCMC and professor and vice chair of the department of psychiatry at New York Medical College.

Crisis Intervention Mode

Former APA President Joseph T. English, M.D., chair of psychiatry at SVCMC and professor and chair of the department of psychiatry and associate dean of New York Medical College, told Psychiatric News that the Greater New York Hospital Association compiled a database of patients who were brought to hospitals in Manhattan and New Jersey from the World Trade Center. The staff had those lists available at the family support center, said English.

A 24-hour mental health help line was also set up at St. Vincent’s in Manhattan for people having trouble coping with the emotional trauma caused by the disaster, Eth told Psychiatric News.

“We have been primarily in crisis-intervention mode, offering information or one-time counseling to the large numbers of people who have come in person to the family support center or have called our mental health help line,” said Eth, an expert in posttraumatic stress disorder.

“In addition, our attending and resident psychiatrists have dispensed psychotropic medications as needed. We are now transitioning to grief counseling and brief therapies,” Eth added.

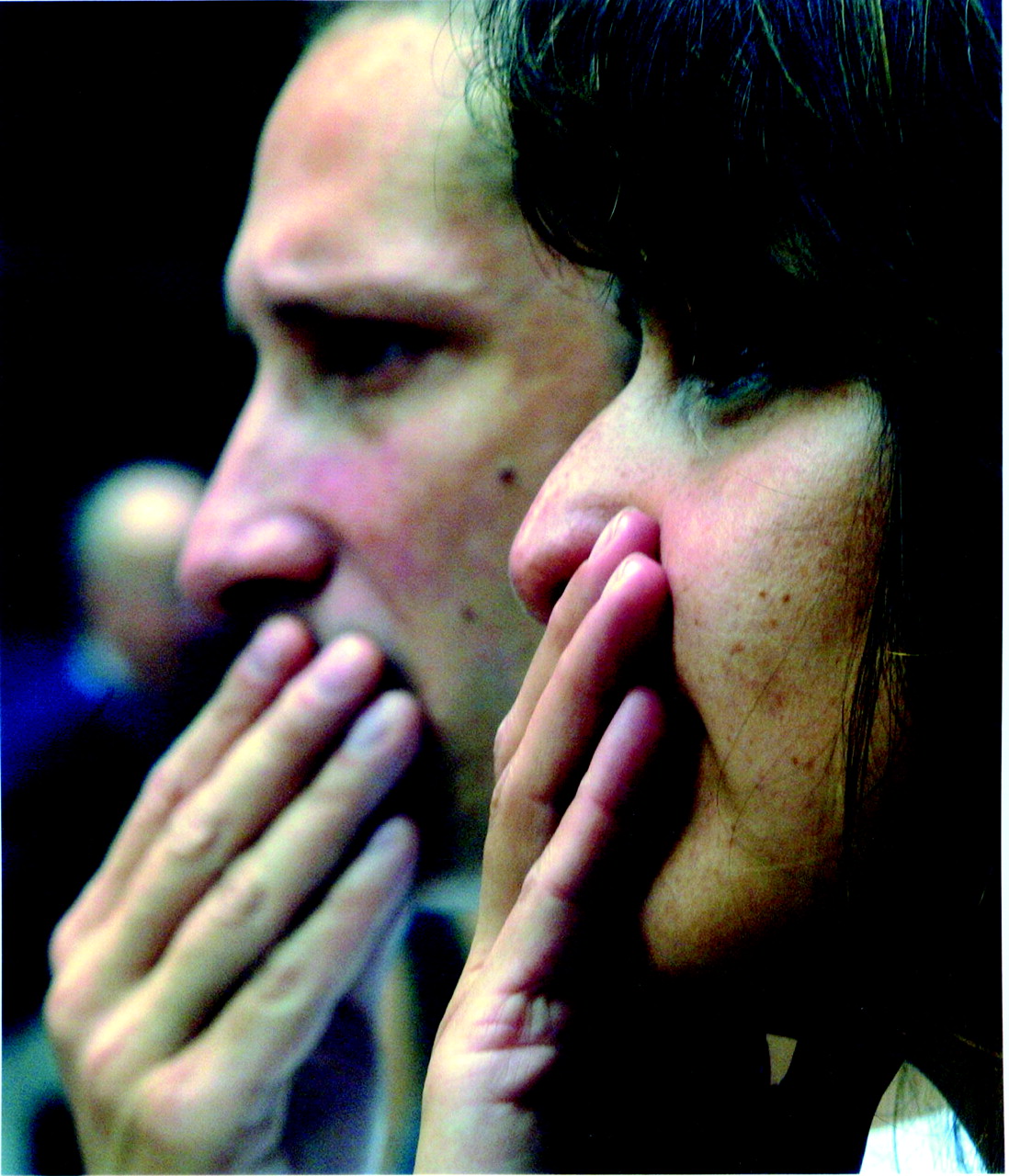

English said, “The most moving thing for me was seeing family members desperate for information about their loved ones, pleading with anyone they could find on the streets to take Xeroxed pictures of their relatives. We encouraged the family members to go to the family support center,” said English.

Eth and English praised the outpouring of volunteer professionals who participated in the mental health response at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Manhattan. He also credited the staff at St. Vincent’s Medical Center in Staten Island with assisting local rescue workers and their families and the staff at St. Vincent’s Medical Center in Westchester County with helping with the mental health help line.

English mentioned that a psychiatric resident from as far away as Massachusetts General Hospital arrived at the family support center within a day of the attack to offer his assistance.

St. Vincent’s Hospital in Manhattan has also sent mental health teams to local schools and businesses that have suffered traumatic losses, said Eth. “We have done several consultations to companies that have lost employees in the disaster.”

At press time, more than 6,000 people in the two towers had not been accounted for.

“The first week of the disaster, we also met with a large group of teachers from an elementary school overlooking the World Trade Center to discuss how to talk to the students. We are planning to do more school consultation services in the weeks ahead,” said Eth.

Responses From Other Institutions

Psychiatrists at several institutions in Manhattan responded to the attacks on the World Trade Center by providing crisis counseling to survivors, relatives, friends, employers, and schools affected by the tragic events.

Among those institutions were Bellevue Hospital, Lenox Hill Hospital, New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York Psychoanalytic Institute (NYPI), and New York State Psychiatric Institute (NYSPI) at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Herbert Pardes, M.D., CEO and president of New York Presbyterian Hospital, told

Psychiatric News that the psychiatry departments of Weill-Cornell and Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Centers have helped counsel many of the estimated 500 survivors brought to their facilities. That number included 25 burn patients taken to the Weill-Cornell Burn Center. Psychiatrists have also counseled people at the Armory, which set up a center for missing persons; the World Trade Center; and other public places, said Pardes.

“I have visited some of the patients including the burn victims who told us stories of unimaginable horror,” said Pardes.

One woman said she was on the 70th floor of the north tower right before it collapsed. She was trying to help her boss, who had suffered a broken leg. As she waited for an elevator, the doors opened and a fireball incinerated several people waiting to get on. Badly burnt, she managed to escape before the tower collapsed. “She felt enormous guilt that she got out and her boss apparently didn’t,” said Pardes.

“Our hospital also lost three emergency services medical workers who rushed to the World Trade Center when the planes crashed and were inside rescuing people when the buildings collapsed. In addition, some of our medical colleagues lost friends and family members in the WTC attack,” said Pardes.

While their morale was shaken, they kept working. “I know of firefighters and emergency medical technicians who sought cover from the debris but kept trying to rescue people despite the black soot filling the air and irritating their eyes and lungs,” said Pardes. “Meanwhile, they are worried that some of their colleagues didn’t make it.

“I was also impressed with the house staff who gave up their vacations to help at the hospitals and the numerous people who donated blood, food, and clothing,” he continued.

John Oldham, M.D., acting chair of the department of psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons and director of NYSPI, told Psychiatric News that the psychiatry department has been providing counseling to numerous victims and people who lost relatives and friends, including medical colleagues.

“We have also sent trauma experts to meet with the police, firefighters, and unions,” said Oldham, who is also chief medical officer for the New York State Office of Mental Health.

“In addition to responding to the acute psychiatric crisis, loss, and bereavement, we want to identify people who are at risk of developing unresolving posttraumatic stress disorder and provide them with appropriate counseling. People who are at particular risk include those with a previous psychiatric history and survivors who were in the building and witnessed the horror,” said Oldham.

About 100 of NYPI’s psychiatrists and psychologists, mainly in private practices, volunteered to staff the institute’s crisis counseling center and help line and participate in outreach to businesses, fire stations, schools, and public places such as bookstores, according to Gail Saltz, M.D., chair of public information for NYPI.

Saltz told Psychiatric News that some NYPI members have also talked to distraught relatives of employees missing in the WTC attack. “For example, Cantor Fitzgerald, a large securities firm on the top floors of the north tower, lost 700 employees. The firm rented space at a Manhattan hotel, where our members talked informally to relatives, many of them young wives with children, who were still in shock,” said Saltz.

Saltz and other members have visited local fire stations in their communities. “I spent a couple of hours recently listening to firemen who lost seven of their colleagues responding to the WTC attack. They seemed relieved when I told them that it was normal to have feelings of fear and aggression toward the perpetrators and to imagine and relive how their coworkers and others died,” said Saltz.

The NYPI also sent members to Barnes and Noble bookstores in Manhattan on several afternoons to talk informally to interested people about their reactions and concerns. The chain of bookstores agreed to provide free books on trauma and grief and hot chocolate, said Saltz.

Disaster Psychiatry Outreach (DPO), which is based in Manhattan, has also worked around the clock since the attacks occurred. Anand Pandya, M.D., secretary and vice president for external relations, told Psychiatric News that the DPO was asked by the New York City Department of Mental Health to coordinate and deploy dozens of volunteer psychiatrists to various sites. These include ground zero, the Armory, and a community center, said Pandya.

“Many city hospitals and the New York State Office of Mental Health have loaned us their workers to help families search for their loved ones, support rescue workers, and staff various hotlines,” said Pandya. “We have also provided medications as needed and hospitalized a few rescue workers.”

At press time, the psychiatrists interviewed for this article said that they planned to continue providing services as long as they are needed. “In the next few weeks, we will see more cases of acute stress disorder, adjustment disorder, and major depression and eventually cases of posttraumatic stress disorder,” said Pandya.

A number of APA district branches sprang into action immediately following the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. The next issue will report on their activities. ▪