The tragic and frightening events last month at the World Trade Center and the Pentagon raise many questions about the long-term impact of trauma. Results from a new study may help answer some of those questions.

The study suggests that the number of Americans who are psychologically impaired in the wake of highly traumatic events may be much higher than previously thought. The study was conducted by Randall Marshall, M.D., director of trauma studies at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, and colleagues and reported in the September

American Journal of Psychiatry.Marshall and his team focused on 9,358 persons who visited one of 1,521 sites that participated in National Anxiety Disorders Screening Day in 1997. Undoubtedly, these individuals did not constitute a cross sample of the American population since they sought out anxiety testing; nonetheless, the sample size was large and broadly distributed throughout the United States.

The 9,358 persons at the sites were asked whether they had ever experienced a highly traumatic event, such as being the victim of a serious crime, being in a bad car accident, seeing someone seriously injured or killed, being sexually assaulted, and so forth, and if so, whether they had experienced at least one month later one or more of the following symptoms: re-experiencing the trauma through recurrent dreams, preoccupations, or flashbacks; insomnia; trouble concentrating; having a short temper; avoidance of any place or of anything that reminded them of the original traumatic event; withdrawal or loss of interest in important things; or inability to experience or express emotions.

Twenty-eight percent of the 9,358 persons reported that they had experienced such an extremely disturbing event and had experienced at least one or more of the mentioned symptoms at least one month later. Nine percent of the 28 percent reported that they had experienced all four symptoms and thus met the criteria for full posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The remaining 19 percent of the 28 percent reported that they had experienced anywhere from one to three of the symptoms and thus had what the researchers considered to be subthreshold PTSD.

“The important public health implication of these findings,” Marshall and his colleagues wrote in their report, “is that substantially greater numbers of individuals experience disability after trauma than is suggested by simply considering rates of full PTSD.”

What’s more, the many Americans who are psychologically disabled by traumatic events may be susceptible to anxiety disorders and depression, the study suggested. Specifically, the greater the number of PTSD symptoms that subjects reported, the greater their chances of also suffering from anxiety disorders and/or major depressive disorder, the researchers found.

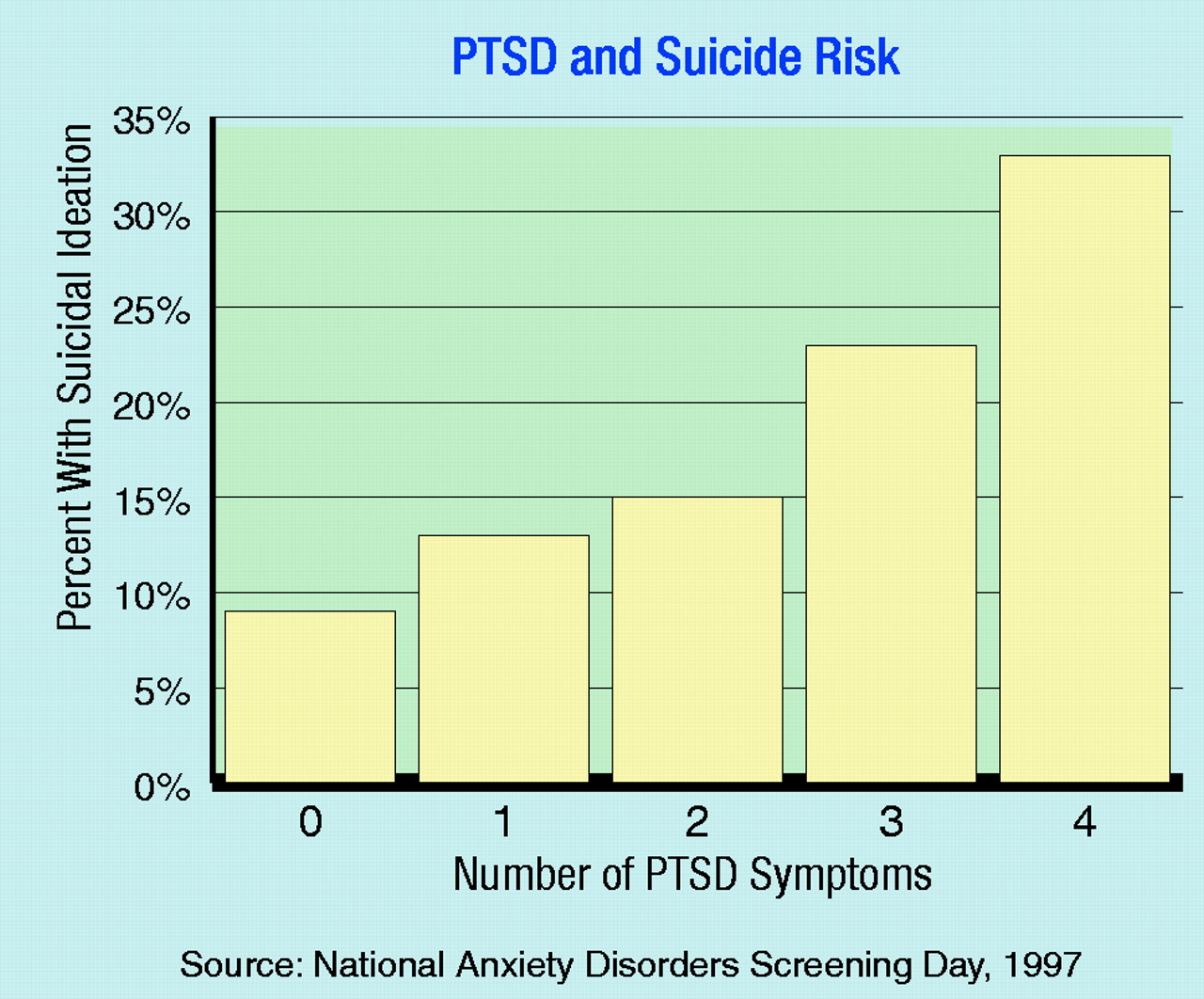

The many Americans who are psychologically crippled by traumatic events may also be at risk for suicide, the study implied. Specifically, a linear association was found between the number of PTSD symptoms that subjects reported and whether they had been contemplating suicide during the previous month. For instance, whereas only 13 percent of those with one PTSD symptom had been thinking about suicide in the past month, 15 percent with two symptoms had, 23 with three symptoms had, and 33 with four symptoms had (

see chart).

If psychological incapacitation in the wake of traumatic events is a much greater health problem than previously thought, and if subthreshold PTSD as well as full PTSD are often accompanied by anxiety disorders, major depression, and/or thoughts of suicide, what can clinical psychiatrists do about it?

First off, Marshall explained to Psychiatric News, “You really have to ask patients directly about their trauma histories. The reason is that it is not picked up the vast majority of the time even when people are in some kind of a treatment situation...It may be because they are ashamed of bringing it up or because it is the nature of the disorder to be wary of someone who might potentially hurt you or who might seem like a powerful figure.”

Secondly, Marshall said, “I think clinicians should consider doing a broader assessment than simply the presence or absence of PTSD. They should also consider that a subthreshold PTSD symptom pattern could also be associated with very serious disability, including suicidal ideation. That is the message there. In other words, do not follow the DSM like a cookbook.” This advice, he added, is especially pertinent in view of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon, where not just thousands of Americans were directly affected by the events, but where millions of Americans were indirectly affected as well.

Finally, Marshall said, “our assumption, until it is studied, is that you would treat [subthreshold PTSD] the same way you would treat PTSD—that is, you could recommend the range of psychotherapies and medications that have been shown to be effective. And I would suspect that you would see as good a response, or perhaps an even better response, than you see with the full syndrome.”

“Comorbidity, Impairment, and Suicidality in Subthreshold PTSD” is posted on the Web at ajp.psychiatryonline.org under the September issue. ▪