About half of all Americans would rather not vote for a political candidate with a mood disorder, according to new survey findings released at an October 1 press briefing in Washington, D.C., by the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (DBSA).

DBSA President John Bush and Executive Director Lydia Lewis introduced the survey findings in the context of a political imbroglio that took place 30 years ago.

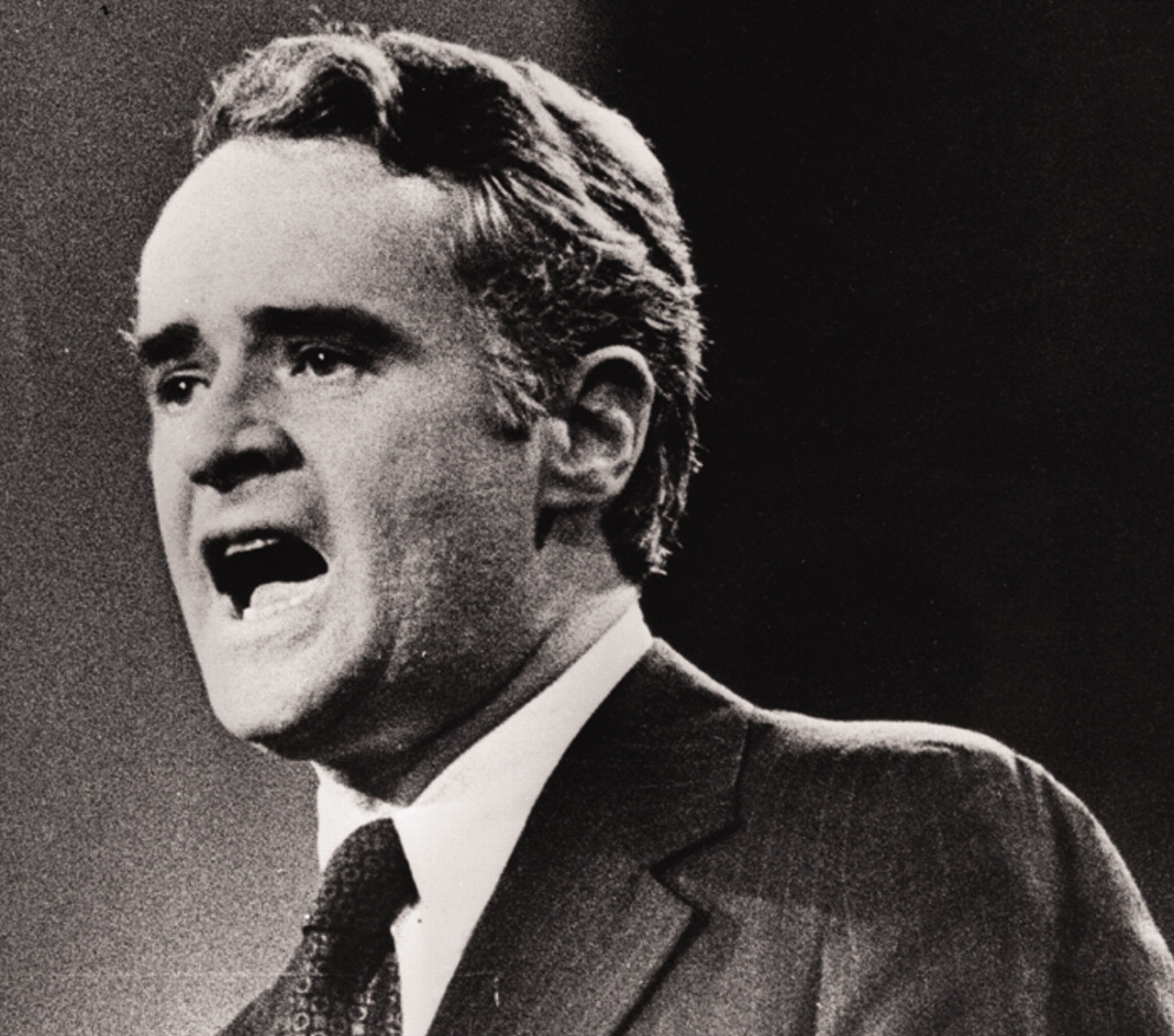

In the summer of 1972, presidential candidate George McGovern chose then Sen. Thomas Eagleton as his running mate. However, Eagleton was removed from the ticket in a matter of days when reports surfaced that he had undergone electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for “nervous exhaustion.”

“Looking back, many have felt that the controversy over Sen. Eagleton’s nomination was both tragic and unnecessary,” said Lewis.

Lewis said DBSA commissioned the survey to find out whether the same firestorm of controversy would have erupted if Eagleton were running for vice president today.

In a telephone survey in July and August, researchers interviewed 1,200 randomly selected adults. They found that 24 percent of respondents would not vote for a political candidate with a mood disorder, and an equal percentage “might not vote” for such a candidate.

Further, 25 percent said they believe that people with mood disorders are dangerous, can easily be identified in the workplace, and cannot form and maintain long-term, stable relationships. A fifth (19 percent) said that people with mood disorders should not have children.

DBSA is a patient-directed organization that provides the public with information on mood disorders. The Chicago-based organization maintains a toll-free help and referral line for those in need of assistance and runs 1,000 support groups for people with mood disorders and their families. In August the organization changed its name from the National Depressive and Manic Depressive Association to its current name.

Living in Ignorance

Most of those surveyed admitted that they knew little about mood disorders. Just 36 percent said that they were “very” or “somewhat” knowledgeable about depression, and 16 percent considered themselves knowledgeable about bipolar disorder.

“Education is paramount,” Lewis said, to eradicate stigma surrounding mood disorders. Her statement was in response to the finding that 60 percent of Americans were not interested in learning more about mood disorders.

Lewis said that this statistic will not discourage DBSA from disseminating information on mood disorders through its newsletters, speakers bureau, media projects, health fairs, and Web site. “We are proactively educating the public,” she said, adding that “people won’t be interested in learning about mood disorders if they are just sitting at home. That’s why we are out there pushing our message.”

Not All Voters Bothered

About two years ago, Rep. Patrick Kennedy (D-R.I.), one of the panelists at the press briefing, told his constituents that he had been diagnosed with and treated for clinical depression. Despite this admission, Rhode Island voters returned him to Congress with 67 percent of the vote.

Kennedy’s disclosure has brought him closer to many of his constituents, he said. “People have been responsive to me about my battles with depression,” he said. “I’ve had numerous people approach me during my days as a congressman and say, ‘Thank you for what you said. I have a similar problem.’ ” Although many people have “self-identified,” or told Kennedy about their own depression, the undercurrent of the disclosure, he said, is “let’s keep this our little secret,” he observed. “That’s the problem.”

He remarked that as the leader and co-founder of a congressional caucus on asthma, he has seen that people have no problem attending related meetings. “Yet if I held a caucus on depression, I’d be lucky to gather a handful of people.”

Kennedy lamented that the National Institutes of Health devoted just $5 of every $100 to researching mental illness. “This speaks to the depth of the prejudice [against people with mental illnesses].” Kennedy also read a letter written September 30 by former Sen. Eagleton about attitudes toward candidates with mood disorders.

“When I was a youngster growing up in the 1930s and 1940s,” Eagleton wrote, “no one would speak the ‘C’ word (cancer).” In later decades, “no one would speak the ‘D’ word (depression).”

Eagleton commented in the letter that he never criticized McGovern for dropping him from the ticket and added, “In 1972, if I was the presidential nominee and George was the vice-presidential nominee, I think I might even have dumped him. The Eagleton matter was overwhelming all of McGovern’s issues.”

Panelist Martha Manning, Ph.D., was in a unique position to speak about the stigma surrounding mood disorders. Manning is a clinical psychologist, award-winning advocate for people with mental illness, and author of Undercurrents: A Therapist’s Reckoning With Her Own Depression. She has battled depression for more than 20 years.

Manning relayed a story about how she is still paralyzed at times by the stigma directed at her. One Sunday night, she was relaxing at home and realized that she was out of lithium. Dressed in her worst sweat clothes, “as close as I could possibly be dressed to being in bed,” she went to the grocery store to refill her prescription.

When she arrived, there were many other people waiting to refill prescriptions. Manning was standing with them “when all of a sudden from on high, the pharmacist yells down into the crowd, ‘Manning?’ My first mistake was when I answered, ‘Yes?’ ”

The pharmacist asked her loudly whether she wanted her lithium in easy-open or child-proof caps.

“It was as if the crowd pulled away from me,” Manning said. In another situation, she added, she would have asked to see the supervising pharmacist to talk about the breach of confidentiality. “But this was lithium. And I was not going to go up in my crummy sweat suit with my hair standing up.”

She resigned herself to saying nothing. “Being assertive in this situation would have been translated into who knows how many different ways as I became justifiably angered over what was done. So I was silenced.”

At times, Manning said, even medicine and psychotherapy have not kept her from contemplating suicide. Her doctors recommended that she have ECT, and she has, four times, she said. But even after decades of working with patients and combating stigma through education and advocacy, Manning is vulnerable. “Do I still feel stigmatized? Yes. Still feel flashes of shame? Yes.”

APA Fights Stigma

APA Medical Director Steven Mirin, M.D., attended the briefing and expressed optimism about APA’s role in erasing stigma through a variety of efforts. He later told Psychiatric News, “The fight against stigma has been waged on a number of fronts—in the media, where unfortunately the vestiges of stigma remain, and in the arena of public education, where APA has had a leadership role.”

He explained that in the wake of last year’s terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, D.C., APA’s work through the National Partnership for Workplace Mental Health “is sensitizing employers to the prevalence of mental illness in our society, but also to the cost of these disorders in terms of absenteeism, lost productivity in the workplace, and human suffering.”

APA created the partnership program in December 2001 to address the often-unmet mental health needs of employees. Several corporations, such as Delta Airlines, Dupont, and Coca Cola, have collaborated with APA to improve mental health in the workplace.

More information about the National Partnership for Workplace Mental Health is posted on the Web at www.workplacementalhealth.org. ▪