For many college students who drink, the party is over. Drinking to excess by college students contributes to 1,400 deaths, 500,000 injuries, and 70,000 cases of sexual assault and date rape each year, according to a study supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA).

“A culture of high-risk drinking prevails on many college campuses,” said Raynard Kington, M.D., Ph.D., acting director of NIAAA, at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., last month. “Parents, prevention organizations, the alcohol beverage industry, and the federal government must all work together. . .to address this problem,” he said.

Kington appeared with Ralph Hingson, Sc.D., M.P.H., who is a professor of social and behavioral sciences at the Boston University School of Public Health and led the study on college drinking.

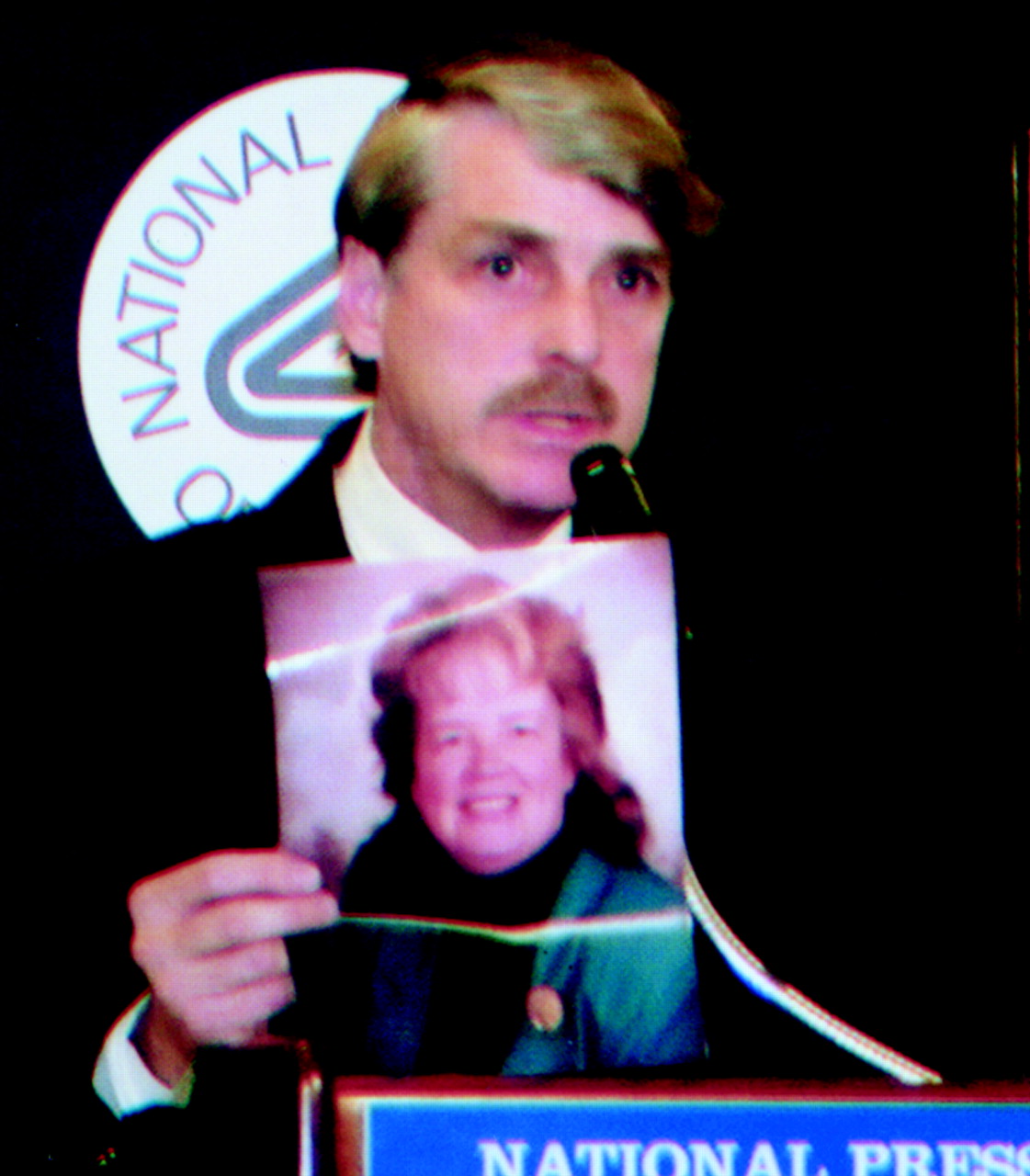

Hingson held up glossy photos of Jonathan Levy, a college student at Radford College in Virginia, and Margaret Moore, a faculty member at the college. Hingson dedicated his paper to the memories of these two people, whose lives ended tragically in October 1997. They had been in a car accident caused by a college student who had been driving while drunk.

Alarming Facts

“We believe that our projections are conservative,” Hingson said about the statistics related to alcohol in the deaths of thousands of college students. The study appears in the March issue of the Journal of Studies on Alcohol.

Hingson found that each year among the 8 million college students in the U.S. aged 18 to 24, there are 1,100 alcohol-related traffic deaths and 300 other accidental alcohol-related deaths. These result from gunshot wounds, falls, drowning, burns, and suffocation.

Hingson and his colleagues estimated the number of alcohol-related deaths from several sources, such as the Department of Transportation Fatality Analysis Reporting System, the National Highway Traffic Administration Fatality Analysis Reporting System, and the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control of the National Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

To come up with statistics on such high-risk, alcohol-related behaviors, the researchers examined the results from the CDC College Health Risk Behavior Survey from 1999 and extrapolated the findings to the U.S. college population.

These data showed that of the 8 million college students aged 18 to 24 in the United States, 39 percent, or 3.1 million, ride at least once a month with a driver who has been drinking. Around 26.5 percent, or 2.1 million, drive under the influence of alcohol at least once each year.

Data from the 1999 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Survey showed that 71,000 students each year are the victims of sexual assault and date rape related to other students’ drinking. In addition, an estimated 630,000 college students are assaulted or hit each year due to other students’ drinking, and 500,000 are injured each year due to their own drinking.

Data from the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse led researchers to estimate that 42 percent of the 8 million college students, or 3.3 million, have binge-drinking habits, defined as having five or more drinks on at least one occasion each month.

“Clearly, the magnitude of this problem indicates that there is a need for us to expand our prevention, screening, and treatment programs to address college drinking,” said Hingson.

Last month the NIAAA sent the results of the study, along with a report by its Task Force on College Drinking, titled “A Call to Action: Changing the Culture of Drinking at U.S. Colleges,” to the presidents of approximately 3,600 colleges and universities across the nation. The task force is made up of about three dozen college presidents, scientists, and college students. NIAAA’s National Advisory Council formed the task force in 1998 amid growing concerns over drinking on college campuses.

One College President’s Perspective

The Rev. Edward Malloy, C.S.C., president of Notre Dame University and task force cochair, has seen the consequences of dangerous drinking by a college students firsthand.

In remarks at the National Press Club last month, Malloy recalled a knock on his door a number of years ago and the words that followed: “There is a woman in the basement, and we think she is dead.” Malloy found a girl who weighed approximately 100 pounds and had reportedly consumed 11 vodkas. “My first reaction was to wonder whether she was alive,” he said.

Her parents were called and told that their daughter would be taken to a nearby emergency room. When the parents arrived, they were shocked and wondered how such a thing could have happened.

“When you are a college president, you are entrusted with a formal responsibility for these young people,” Malloy said.

While the girl survived, other students have not been so lucky. Malloy spoke of presiding over the funeral liturgy for a student who was in a car accident while drinking and driving, and another student who was killed by a drunken driver.

“What do you say? How do you have an impact?. . . We are committed to making a difference,” Malloy said of the task force’s work. “If we can save one student from harm, it was worth it.”

Possible Solutions

Many strategies to reduce drinking on campus have failed, according to the task force report, because these efforts have been sporadic or missed the mark.

According to task force cochair Mark Goldman, Ph.D., a professor of psychology at the University of South Florida, a major problem is creating a message that will attract students’ attention in the first place. When campuses post signs about the dangerous consequences of drinking, or even pictures of cars crumpled in drunken-driving accidents, students ignore them, he said.

Efforts aimed at regulating student course loads have been found to be a promising intervention, according to Goldman. One idea is to have students take courses Monday through Saturday. “Students have learned how to avoid taking classes on Fridays,” he said, so that they can begin drinking on Thursday nights. Ultimately, Goldman said, a cooperative effort is necessary to save thousands of students from death and injury related to drinking each year.

“The community, parents, college administration, students, and the alcohol industry must all be on the same page at the same time in order to make a difference.”

More information about NIAAA’s report, “A Call to Action: Changing the Culture of Drinking at U.S. Colleges,” is posted on the Web at www.collegedrinkingprevention.gov. ▪