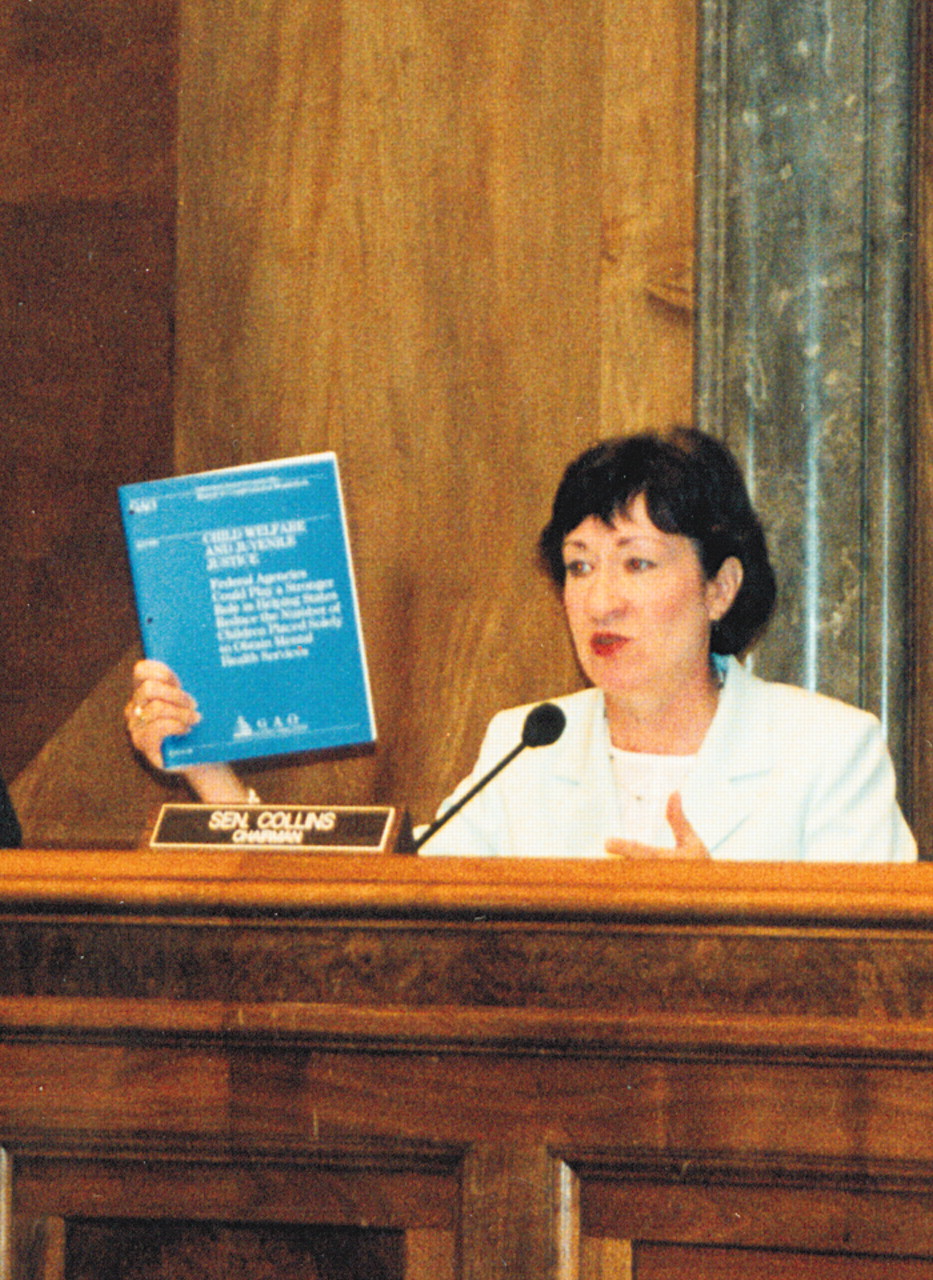

Sen. Susan Collins (D-Maine), chair of the Senate Governmental Affairs Committee, held two hearings last month to investigate why so many parents relinquish custody of their children to the state to obtain mental health services for them.

A recent General Accounting Office (GAO) report commissioned by Collins and Reps. Patrick Kennedy (D-R.I.) and Pete Stark (D-Calif.) found that in 2001 about 12,700 children were placed in the child welfare or juvenile justice system in the United States by their parents or guardians (Psychiatric News, June 6).

“In some extreme cases, families are forced to file charges in court against their children or declare that they have abused or neglected them,” said Collins.

Pat Cooper, a mother from Arkansas, described her family’s ongoing ordeal to obtain intensive mental health services for 12-year-old Dakota.

“Dakota suffers from multiple mental illnesses including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. His behaviors include attempting to set fires and using knives in a dangerous way,” said Cooper.

“He cannot be left unsupervised anywhere or anytime. Unfortunately, our private insurance did not cover the intensive community and home-based mental health services needed to keep Dakota at home. Because my husband and I both work, we didn’t qualify for Medicaid.”

Dakota was placed in a residential treatment center where he did well and returned home. Despite asking the Department of Human Services to provide follow-up services and support, none was provided, testified Cooper.

Dakota then began a cycle of being placed in residential treatment centers and returning home without access to follow-up mental health services, said Cooper.

With nowhere else to turn for help, the Coopers agreed to place Dakota in therapeutic foster care. “Dakota lived with a family four hours from our home for 11 months. The state used an abuse and neglect proceeding to place Dakota in foster care, and my husband and I were then treated by the foster care system as parents who abused and neglected our son. It was painful and humiliating,” Cooper testified.

Cynthia Yonan of Ohio, a mother of twin boys diagnosed with bipolar disorder and other problems, testified that her sons quickly consumed the 90 days that her private insurance plan provided for inpatient psychiatric care.

“Despite losing my job and income, Medicaid wasn’t an option for mental health services because I owned my home, [and its value] exceeded the law’s strict minimum asset requirement.”

Yonan and Cooper were told by state case workers that they had to turn over custody of their children to the state to secure intensive mental health services, an option they both refused.

“Frankly,” said Yonan, “I was shocked when faced with this agonizing prospect. I could not help wondering if families with children with other brain illnesses, like cancer, were asked to turn their child over to the state for treatment.”

Her two-year search for mental health services for her sons finally paid off. She learned about the Community Residential Services Authority (CRSA), “a well-kept secret that was offered to me after years of struggle and when it became clear I was not going away,” testified Yonan.

The state agency was created for children who do not fit the criteria for services established under the departments of Child and Family Services, Mental Health, and Corrections and the Illinois Care Grant, said Yonan.

“I am pleased to report that with the guidance and help of CRSA, my sons were placed in a residential treatment facility in July 1999. The treatment they have received has made a significant difference and given us hope for a brighter future,” Yonan testified.

Theresa White of Maine was less fortunate. Her 16-year-old daughter, Heather, suffers from bipolar disorder. “Psychologists didn’t want her to be labeled with that at age 9, so instead Heather received lots of other labels, including delinquent, addict, violent, and runaway,” said White.

“After six years of struggling to find and gain access to appropriate services, I was told that the only option for keeping her safe was residential treatment and that I would have to relinquish custody of Heather to the state,” said White.

White described relinquishment of her daughter in July 1999 as “the ultimate human sacrifice” and “the most devastating day of her life.”

Afterward, Heather entered and was subsequently discharged from several residential treatment programs for assaulting staff or running away, said White.

“When no placement was available, the Department of Human Services sent her home without transitional services, including school and mental health treatment,” complained White.

Heather was sent to a locked behavioral treatment facility last year. “For the first time, she began to receive treatment for both mental health and substance abuse issues,” testified White.

White has been unsuccessful at regaining custody of Heather despite repeated attempts. “I have been guaranteed inclusion but have been excluded. My relationship with my daughter has been damaged because case workers and members of my daughter’s treatment team have ignored my court-ordered right to visit and be involved,” said White. “Custody relinquishment devalues and undermines the importance of family unit and the role it plays in society.” ▪