What is the neuropsychology of psychotic depression anyway—is it more closely related to schizophrenia or to depression? A new, rigorously controlled study suggests that it is a lot closer to schizophrenia.

The study was headed by S. Kristian Hill, Ph.D., of the Center for Cognitive Medicine at the University of Illinois at Chicago and appeared in the June American Journal of Psychiatry.

The neuropsychological profile of psychotic depression, especially in early and mid adulthood, has received little investigation. Data are inconsistent, often methodologically limited, and potentially confounded by the effects of chronic disease and exposure to antipsychotic treatment. So Hill and her colleagues studied whether the neuropsychology of psychotic depression is closer to that of schizophrenia or that of nonpsychotic depression.

They recruited 106 patients who were consecutively admitted to the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center for a psychotic disorder on the basis of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R or DSM-IV (SCID). Of the 106 patients, 86 were diagnosed with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder or schizoaffective disorder and the 20 with unipolar depression with psychotic features.

Before any of these patients were treated for their psychosis, they were given a battery of neuropsychological tests that assessed general intelligence, executive function, attention, verbal memory, motor skills, and visuospatial perception. At the time of neuropsychological testing, the examiners were unaware of the subjects' diagnoses.

“To our knowledge,” the researchers asserted in their study report, “this is the first study to provide data that document the neuropsychological profile of psychotic depression in young adults at the time of the first episode of illness, before treatment with antipsychotic medication.”

The scientists then selected 14 other patients who had been diagnosed as having a nonpsychotic unipolar depression, as well as 81 healthy individuals with no history of psychiatric treatment and no Axis I disorder.

The unipolar depression patients stopped taking antidepressant medication for at least three weeks before the start of the study to avoid a direct medication effect on the study results. The investigators also ensured that these subjects matched the 106 subjects with either a schizophrenia disorder or a psychotic depression on gender, race, education, and parental socioeconomic status. These subjects also completed a battery of neuropsychological tests.

The researchers then assessed the neuropsychological test results from their four groups of subjects.

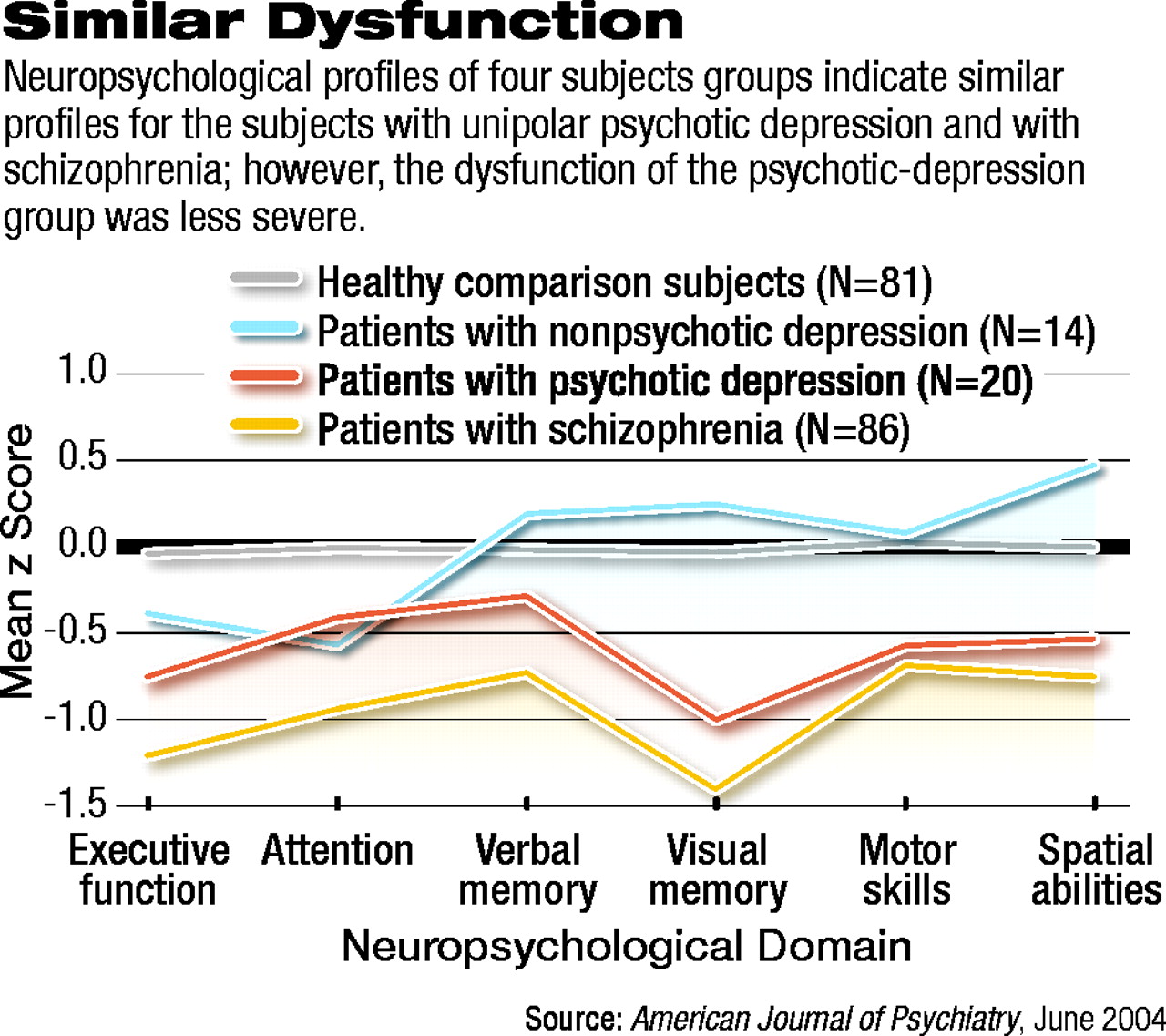

The subjects with psychotic depression were found to have a pattern of neuropsychological dysfunction that was similar to, but less severe than, that of the subjects with a schizophrenia disorder, the investigators found. In contrast, subjects with nonpsychotic unipolar depression had a neuropsychological profile that was similar to that of the healthy control subjects, except for mild dysfunction on tests of attention.

These results, the researchers maintained, suggest that schizophrenia and psychotic depression “may have common pathophysiological features.” And as far as the implications of the findings for clinical psychiatrists are concerned, “they provide further documentation that psychotic depression involves significant neuropsychological impairment,” Michael Thase, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh, and one of the study collaborators, told Psychiatric News. The study was financed by the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression and the National Institutes of Health.

Am J Psychiatry 2004 161 996