As American psychiatrists know, psychodynamic psychotherapy has lost some of its standing as an important treatment tool. Yet before Sigmund Freud rolls over in his grave out of distress over the status of his brainchild, he should know that some heroic efforts are being made to breathe new life into it.,

The attempts have to do with passing psychodynamic psychotherapy on to the next generation of American psychiatrists— and in a way that makes the therapy meaningful to them.

This was the major take-home message of a number of sessions held at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry, held in New York City April 29 to May 2.

Competencies Come to the Rescue

One major effort to ensure that psychodynamic psychotherapy remains a valued treatment option is that all U.S. graduating psychiatry residents must demonstrate competence in five core psychotherapies—brief psychotherapy, supportive psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychodynamic psychotherapy, and psychotherapy combined with psychopharmacology. The competency standards were designed for residency programs throughout the United States by the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training Task Force on Core Competency and the APA Committee on Psychotherapy by Psychiatrists (Psychiatric News, January 18, 2002). The requirement to test residents' competency in the five psychotherapy modalities was implemented by the Residency Review Committee in Psychiatry in 2001.

David Mintz, M.D., director of residency training at the Austen Riggs Center in Stock-bridge, Mass., believes that the competency standards are helping stem the tide regarding the demise of psychodynamic psychotherapy.

Psychodynamic Courses Get Creative

Another crucial attempt to give psychodynamic psychotherapy new life is to pep up psychiatry residency courses on the subject.

One such course is being taught by Elizabeth Auchincloss, M.D., director of psychiatry residency training at Weill Cornell Medical Center. It is directed to psychiatry residents in their second year and presents some of the scientific evidence underpinning psychodynamic psychotherapy. Students are requested, for example, to read a paper by psychiatric geneticist Kenneth Kendler, titled: “What Is the Mind?” They are also asked to read about scientific findings regarding unconscious processes and the role of consciousness in meditation.

Another innovative course is being taught by Eve Caligor, M.D., a clinical professor of psychiatry at Columbia University. She focuses on a model of the mind that she has evolved over a number of years and that she considers a framework for psychodynamic psychotherapy. Residents who have been exposed to this model appreciate it, she reported, and she is optimistic that they will not forget it as they move along in their psychiatric careers.

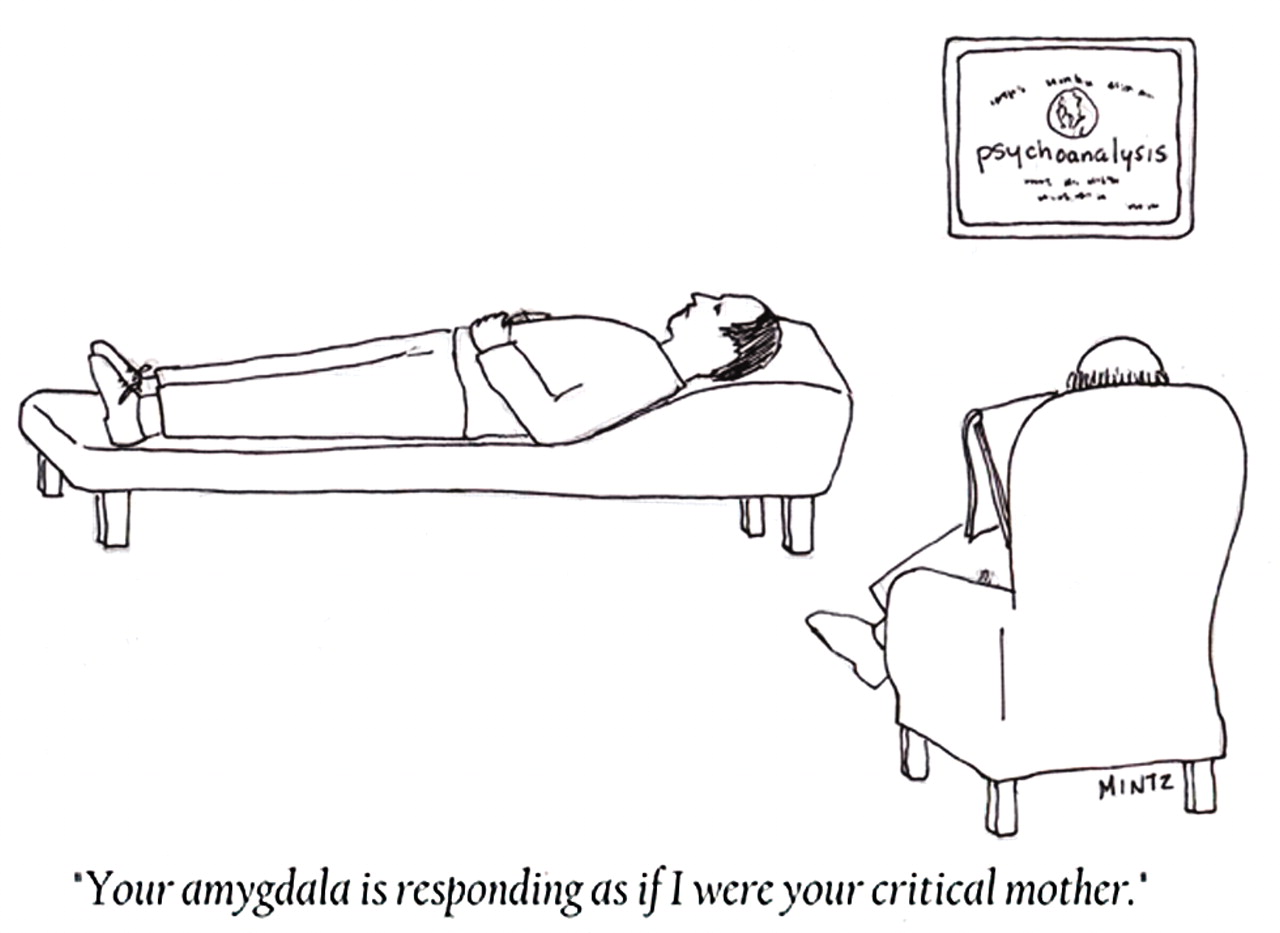

A third course is being taught by Mintz, in which he combines psychodynamic psychotherapy with psychopharmacology. “Residents are hungry to become better prescribers,” he said, “so you can actually teach a lot of psychodynamics by teaching the psychodynamics of pharmacology.”

This course, he pointed out, also dovetails with the new psychiatry residency competency of being able to combine psychotherapy with psychopharmacology.

What does Mintz do in this course? For one thing, he tries to show residents how an education in psychodynamic psychotherapy can benefit them in practical ways. For instance, he said, such an education can reveal to residents why they so often feel distressed or in conflict; it may also help them come to realize that when they fail to help patients, it may be due not just to their personal inadequacies, but to the nature of psychiatry itself.

Such an education can also explain why patients with personality disorders may want to use medications to deaden themselves when they do not want to face something. It can also demonstrate how psychodynamic psychotherapy can be used to help lower patients' resistance to taking medications.

Then Andrew Gerber, M.D., a psychiatry resident at Weill Cornell Medical Center, will be introducing a psychiatry residency course this fall on the crossover between psychodynamic psychotherapy and neuroscience. He not only will be presenting studies on the two subjects of psychotherapy and neuroscience to residents, but also will be discussing some of the challenges of conducting research on psychodynamic psychotherapy—for example, how do you measure therapeutic change in patients, and what is it about the therapeutic alliance that helps patients get better? All of this material, Gerber anticipates, will give residents an idea of where psychodynamic psychotherapy stands today. In fact, it may even prompt some residents to want to do some of this research and move the field forward.

Still other suggestions on how to return psychodynamic psychotherapy to its rightful place were aired at the meeting. For example, Myron Glucksman, M.D., a clinical professor of psychiatry at New York Medical College, suggested that some radical methods are needed to engage in psychodynamic psychotherapy—say, perhaps some could specialize in it.

“I like your idea of having a subspecialty training track for those who would like to specialize in analysis,” a psychiatrist listening to his talk commented afterward.

Then Joel Wallack, M.D., director of psychiatry at Cabrini Medical Center in New York City, suggested teaching an integrated model of the psychotherapies to residents, and afterward they could become experts on specific therapies during later fellowships. ▪