Children are exposed to more acts of violence during their Sunday morning programs than adults are during prime time, say experts on the effect of TV violence on children.

Viewing repeated violent acts on TV often has a negative effect on children's behavior and attitudes. But what happens neurologically when children watch TV violence?

John Murray, Ph.D., a child psychologist at Kansas State University, has studied TV violence in children for about three decades. He is believed to be the first researcher to use functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in young children to study how their brains react to video clips showing violence. He conducted these studies in the late 1990s.

Murray presented the preliminary findings last month at the Head Start Research Conference in Washington, D.C. Head Start and Early Head Start are federally sponsored child-development programs designed to prepare infants and preschool children from low-income families for school.

“The regions of the brain that were activated suggest that viewing violence is emotionally arousing and engaging, and processed by the brain as a real event,” said Murray.

The pilot fMRI study of eight children aged 8 to 13 was conducted at the research imaging center at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. The children, five boys and three girls, had no psychopathology and were from middle- to upper-income families living in San Antonio, said Murray. The study was funded by a grant from the Mind Science Foundation in San Antonio.

The children were shown six three-minute video clips for a total of 18 minutes. Two clips showed violent boxing scenes from the film “Rocky IV,” and two clips showed nonviolent educational programming: the Public Broadcasting Service's “Ghostwriter” and a National Geographic special. The last two clips were neutral controls consisting of a white X on a blue screen.

Murray showed a clip of a violent boxing scene in “Rocky IV” at the Head Start conference. The match is under way between Drago, a huge, robot-like Russian boxer, and Apollo, his smaller, weaker American opponent. Apollo is injured by Drago's forceful punches but insists on remaining in the match.

The conference audience was mesmerized by the violent second round. Drago easily knocks the wind out of Apollo, who is barely standing. Drago becomes more violent and repeatedly punches Apollo's face and head. The clip ends with Apollo pronounced dead on the floor.

Right Brain Activated

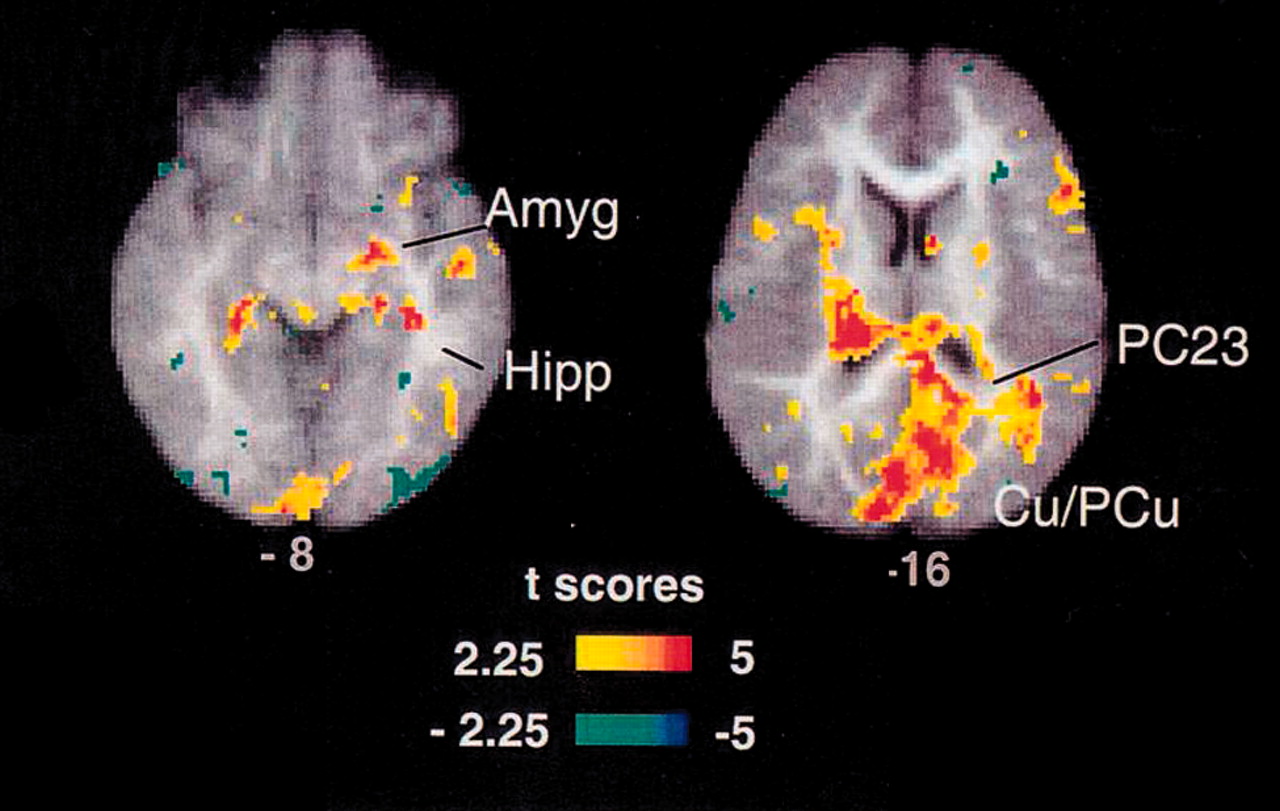

“When that clip was shown to the children in our pilot study, we saw greater activation in right regions of the brain. We thought this might occur, because two previous studies found the right side of the brain processes negative emotional material, and the left side processes positive emotional material,” Murray said.

Significant activation occurred in the right region of the amygdala, the area of the brain that senses danger in the environment and prepares the body for fight or flight, Murray explained.

The researchers did not see the expected significant activation in the prefrontal cortex in the pilot study. The frontal area is where thought processes such as association and planning take place.

Puzzled by Unusual Finding

The researchers saw pre-motor cortex activation, which they found puzzling.“ We knew that children often imitate boxing movements after watching them, which activates the motor cortex,” Murray said. “However, the children in our pilot study couldn't physically move inside the fMRI machines. The pre-motor cortex activation suggests they were thinking about moving or perhaps imitating the boxing movements.”

Another surprise was the activation in the posterior cingulate, an area in the back of the brain that appears to involve long-term memory storage for significant traumatic events, Murray noted.

Studies of war veterans with severe posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have shown activation in the posterior cingulate when the veterans were asked to recall distressing events and images, Murray said.

“The children in our pilot study were not suffering from PTSD, but they were watching traumatic and dramatic violence. This suggests that the brain processes television violence as an actual threatening event, which is stored in the long-term memory area for quick recall,” Murray explained.

The pilot study had several limitations including a small sample size, Murray acknowledged. Next month, he will begin a larger fMRI study at the Center for Media and Child Health in Boston. This is a joint project with Harvard Medical School and Children's Hospital in Boston.

The study is funded by a $500,000 grant from the federal Bureau of Maternal and Child Health in the Administration for Children and Families, said Murray.

The plan is to enroll 60 children aged 8 through 12 in the one-time fMRI study, with an equal number of boys and girls. The study design is cross-sectional to facilitate comparisons between children with a history of physical abuse, aggressive behavior, and normal development, Murray said.

“I expect the abused children to show greater activation in the right regions of the amygdala, pre-motor cortex, and posterior cingulate. I expect to see less activation in these regions in the aggressive children, who may be desensitized already to suffering and violence because of life experiences,” Murray said.

He should know in the next year or two when the study is completed.

Several reports on the impact of television violence in children are posted online