, APA joined with the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI) on September 30 to host lawmakers and their health policy staffs at a Capitol Hill luncheon during Mental Illness Week. The topic was one of recent significance—“What's New in Children's Mental Health Research.”

Held just two weeks after the Food and Drug Administration's public hearings on the use of antidepressant medications in children and the risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, the event gave both organizations the opportunity to focus lawmakers' attention on the facts concerning children with mental illness and specifically the significant lack of access to quality children's mental health care.

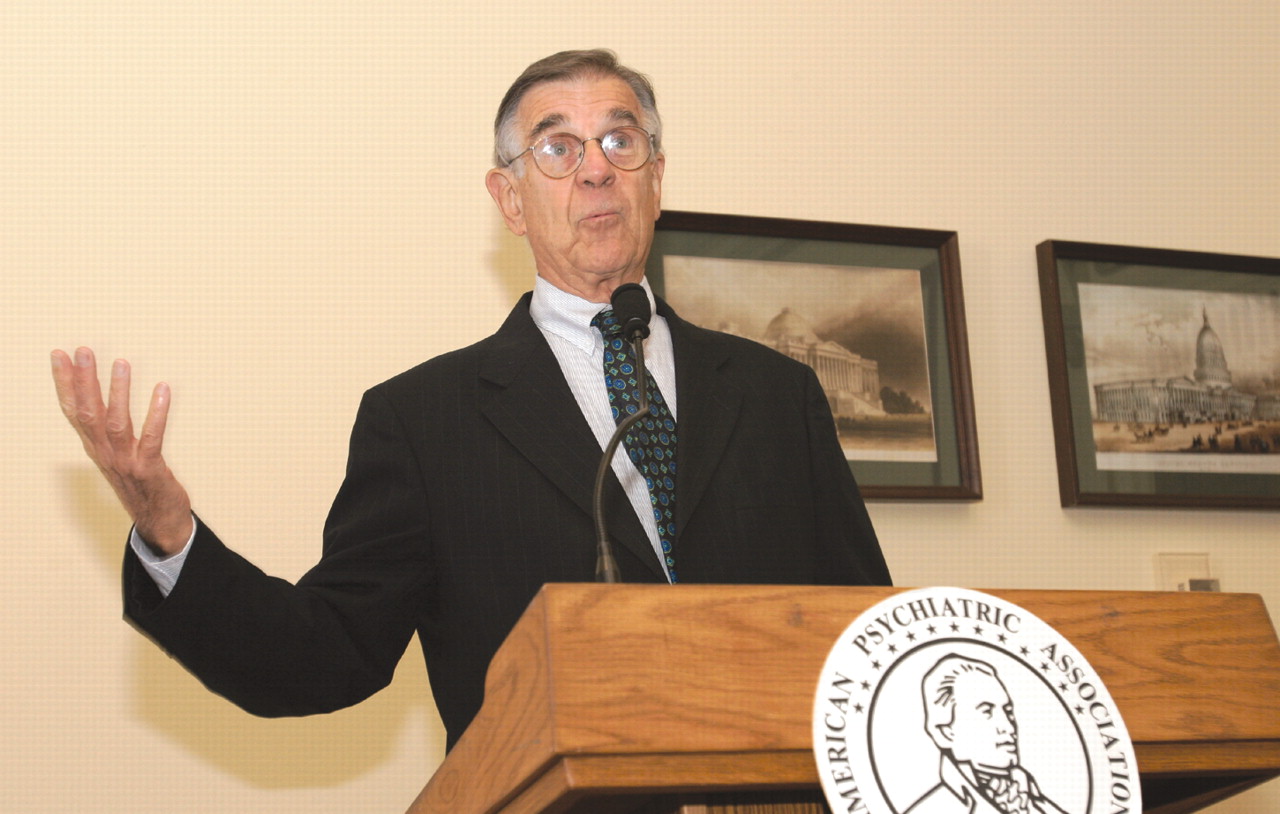

“Thank goodness we are finally paying attention to this very important issue,” said Herbert Pardes, M.D., president and chief executive officer of New York Presbyterian Hospital and a former APA president, who served as host for the luncheon. “We are terribly underinvested in mental health in this country.”

Several members of the House of Representatives attended at least part of the luncheon presentations, including Reps. Tim Murphy (R-Pa.), Joe Wilson (R-S.C.), Pete Stark (D-Calif.), Patrick Kennedy (D-R.I.), Sandy Levin (D-Mich.), Grace Napolitano (D-Calif.), and Barbara Jackson-Lee (D-Calif.).

Following a welcome by APA Medical Director James H. Scully Jr., M.D., Pardes introduced the keynote speaker for the luncheon, Peter Jensen, M.D., director of the Center for the Advancement of Children's Mental Health and the Ruane Professor of Child Psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.

“We must find a way to close the gap between what we know and what we do,” Jensen began, noting that two-thirds of all children in the United States with a diagnosable mental illness receive no care or treatment for their illness.

Jensen said the problem is, at the least, twofold: Americans in general are not sensitive to the warning signs of mental illness in children, creating a fundamental barrier to detection, identification, and diagnosis. While the reasons are many, he continued, one barrier is poor communication between patient/parent and doctor.

Perceptions Differ

“Nearly 80 percent of doctors say that they ask about a child's mental health during an office visit,” Jensen said, citing data from a 2002 survey he and colleagues at Columbia completed. “But only one-third of parents believe the doctors ask that often, and 44 percent of parents stated that their pediatrician never inquires about their child's mental health during routine physical exams.”

The gap must be closed, Jensen said, if children who need help are ever going to be identified. To do so, Jensen detailed a federally funded project he and his colleagues have been working on to identify a set of“ indicators of unmet need—signs that [would lead] any mental health clinician to say, `Hey, this kid needs help.'” That project identified a list of indicators, such as “extreme depression with impairment” or “suicidal, with recent attempt or plan.”

Jensen noted, however, that many parents would not be comfortable with that type of language, so he and his colleagues translated the indicators into a set of “action signs.” Instead of “extreme depression,” words many parents would not use to describe their child, Jensen modified the wording to “extreme sadness and/or emotional withdrawal that last several weeks.” Instead of the term suicidal, parents would be more likely to identify with the description “trying seriously to harm or kill oneself, or making plans to do so.”

Despite the fact that “even the most severely disturbed children are likely to not receive any services, anywhere in the last year,” Jensen continued, the child and adolescent mental health field has made significant progress on building an evidence base of scientifically supported treatments.

“Today we have well-developed and validated tools for both diagnosis and for treatment,” Jensen concluded. “But we are not using them. We know what to do, but we aren't able to do it because we are trapped in a system that won't allow it.”

Americans, Jensen said, must come together to fundamentally change the way we think about mental health care through a combination of policy initiatives that would expand primary care physician-patient time and invest in quality treatment tools for providers. Accurate information about mental health must be disseminated to parents, teachers, legislators, and policymakers, he added.

Following Jensen, David Fassler, M.D., an associate clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of Vermont School of Medicine and APA trustee-at-large, reviewed the FDA's re-evaluation of adverse-event data from clinical trials of antidepressants and discussed the black-box warnings that were widely anticipated at that time (see

page 1).

Signs of Progress Emerging

NAMI Executive Director Michael Fitzpatrick told those in attendance,“ This is truly a time of good news and of significant risk.” He called on legislators to support funding of mental health research through the National Institutes of Health addressing appropriate diagnosis and treatment of mental illness in children and adolescents. He urged Congress to support initiatives to increase the number of mental health professionals specifically trained in the treatment of pediatric patients.

“We can and must do better,” Fitzpatrick said. “Children may represent only a fraction of our population, but they truly are 100 percent of our future.”

Many of the legislators in attendance noted in brief remarks to the group that while they are beginning to see signs of change in Congress, they remain frustrated at the slow pace of that change.

“We must help people to understand that treatment of mental health issues is a vital part of fundamental health care,” said Murphy, himself a clinical psychologist. “When we do this, we'll get lower health care costs by treating the patient instead of the disease.”

Kennedy added that the work of groups such as APA and NAMI are fundamentally “vital in keeping mental health issues in front of members of Congress and their staffs.” He continued, “We have all of these issues that we need to address, but if we don't have basic parity, we'll get nowhere on any of it.”

However, Napolitano said that she is seeing some signs of progress on mental health issues. “There is a beginning, a glimmer of recognition within this House of the issue that you talk about,” she said.“ But you need to keep getting information to your representatives. You need to make them understand that this is in their own backyards. These patients are their neighbors, their coworkers, their constituents.”

Jackson-Lee noted “how frustrating it is that mental health remains a stepchild of the health care system of America. This is 2004, and we are still talking about something so fundamental as mental health parity. We must use the 2005 legislative session to really not give any leeway at all to any leadership [of the House or Senate] that does not support moving us toward mental health parity. You all can be a leading driving force in that, and I encourage you to be steadfast in working with Congress on that goal.”▪