Researchers have identified some medications that help autistic youngsters socialize.

For example, when autistic children were given selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or atypical antipsychotics in open-label studies, they became more spontaneous than before and interacted more with other people than before. However, these medications' putative ability to increase socialization in autistic youngsters has yet to be demonstrated in placebo-controlled trials. Also, it is not yet known whether the purported socialization benefits derive from a direct impact on socialization or via an indirect effect—say, by reducing irritability and anxiety.

Still another medication that looks promising for autistic children is the antibiotic D-cycloserine, a pilot study reported in the November American Journal of Psychiatry suggests. The study was headed by David Posey, M.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at Indiana University and director of the university's autism treatment center.

Various factors prompted Posey and his colleagues to undertake a pilot study to determine whether D-cycloserine might increase socialization in autistic children. In addition to being used to treat tuberculosis for 45 years, D-cycloserine enhances the activity of the neurotransmitter glutamate in the brain. Adding low doses of D-cycloserine to antipsychotics other than clozapine can temper social withdrawal in persons with schizophrenia, several studies have suggested. D-cycloserine has been safely used in children at high doses to treat tuberculosis, and the low doses of D-cycloserine used in persons with schizophrenia have produced limited side effects.

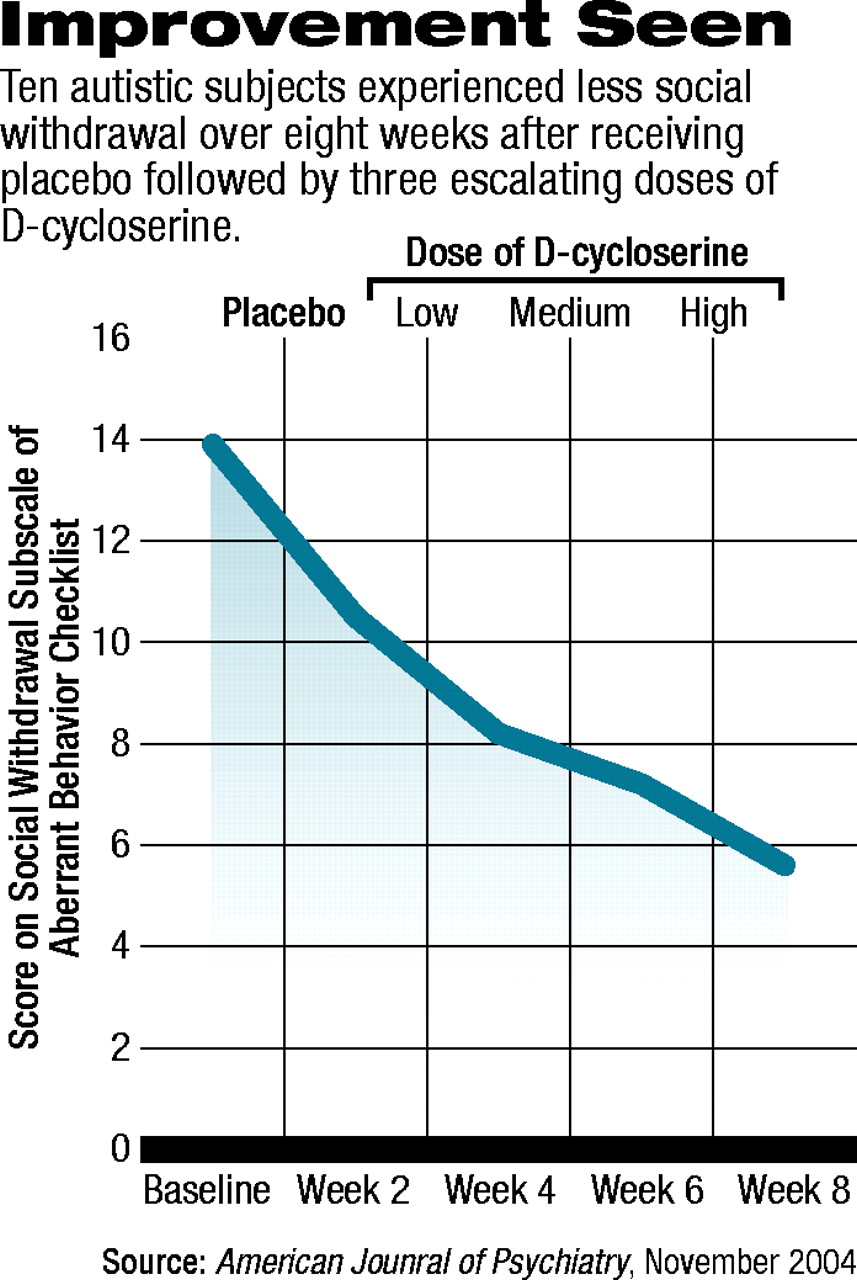

In the pilot study by Posey and his coworkers, 10 individuals who met a DSM-IV diagnosis of autism and who were on average 10 years old received a placebo for two weeks, then three different, ascending doses of D-cycloserine during each of three two-week periods. The daily doses were about 0.7 mg/kg, 1.4 mg/kg, and 2.8 mg/kg, respectively. The subjects' social withdrawal was measured with four yardsticks at the start of the study, at the end of the placebo phase, and at the end of each two-week phase. The yardsticks were the Clinical Global Impression Scale, the Social Responsiveness Scale, a modified Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, and the Aberrant Behavior Checklist.

Test results were encouraging. For example, subjects performed significantly better on the Clinical Global Impression Scale after they had received the medium and high doses of D-cycloserine than they had at the start of the study. Subjects performed significantly better on the social withdrawal subscale of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist after they had gotten the highest dose of D-cycloserine than they had at the start of the study (see chart). In four of 10 subjects, social improvement was clinically meaningful.

One of these four subjects was 5-year-old “Greg.” Greg had been in individual speech therapy and in group social skills training with a speech and language therapist for two years. The therapist was not informed about Greg's participation in the D-cycloserine study. Nonetheless, she noted marked improvement in his attention, spontaneous use of language, and initiation of social interaction while he was on D-cycloserine.

The pilot study was financed by the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD), the National Institutes of Health, a Daniel X. Freedman Psychiatric Fellowship Award, and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-a controlled trial to further explore D-cycloserine's impact on socialization in autistic subjects got under way earlier this year, Posey told Psychiatric News. It is being funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and NARSAD.

Am J Psychiatry 2004 161 2115