A young enlisted man in the military is having romantic, legal, or financial troubles and commits suicide with his firearm.

This is a common suicide scenario in all branches of the armed forces.“ A suicide note left for someone often reveals the person's despair over a spouse leaving the marriage or feeling overwhelmed at work,” said Lt. Col. Rick Campise, M.S.C., chief of the Air Force Suicide Prevention Program, at the 2004 annual Department of Defense (DoD) Suicide Prevention Conference in Arlington, Va.

The October conference was organized by the Suicide Prevention and Risk Reduction Committee, which is chaired by Col. Thomas Burke, M.C., a psychiatrist.

Burke directs the mental health policy program in the DoD Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs. He told Psychiatric News that the committee plans to establish a uniform DoD-wide system that all branches can use to track suicides, suicide gestures, and attempts.

“We currently collect only data on suicides, and each service branch collects data differently depending on the system they use, which limits our ability to analyze trends,” Burke commented.

The idea for the annual suicide-prevention conference came from Burke's predecessor, psychiatrist Col. E. Cameron Ritchie, M.C., who organized the 2002 and 2003 conferences. She is the president-elect of the Society of Uniformed Services Psychiatrists, an APA district branch.

“All the services were doing innovative and exciting work on suicide prevention. I decided to bring key people in the services together with their counterparts in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute of Mental Health,” Ritchie told Psychiatric News.

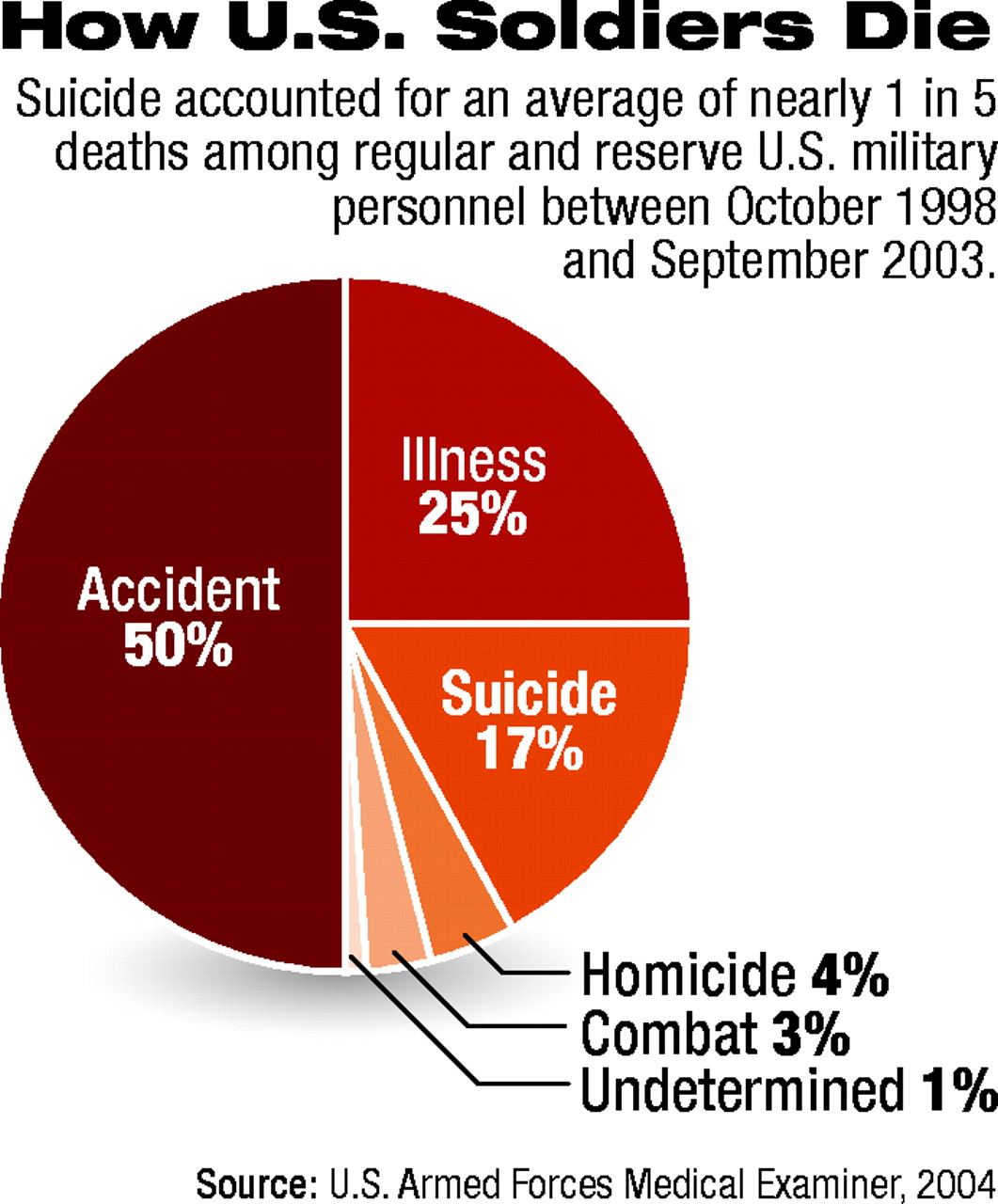

Suicide is the third-leading cause of death for active-duty personnel in the Armed Forces after accidents and illnesses (see chart). Suicide accounts for 17 percent of all deaths among the estimated 2.7 million service members in the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines, National Guard, and Reserves, according to the DoD.

Maj. Lisa Pearse, M.C., a preventive medicine physician, directs the DoD Medical Mortality Registry in the Office of the Armed Forces Medical Examiner. The registry is designed to track all causes of death of active-duty service members, which includes support personnel, according to Pearse. A limitation of the system is that it does not track veterans, lengths of deployment, or repeat deployments.

Young Whites at Most Risk

“Most suicides occur in young white enlisted men in their home or barracks in the United States,” said Pearse. Men make up 85 percent of active-duty members in the armed forces and 94 percent of those who completed suicides in 2003.

Men in general are more likely to die in a suicide attempt than are women because men use more lethal means such as firearms. Women are more likely to attempt though not complete suicide, according to suicide experts.

Nearly half of all suicides (47 percent) among active-duty members of the armed forces in Fiscal 2003 were made by young men and women aged 17 through 24, Pearse said. Those aged 25 through 34 accounted for 32 percent of suicides, those aged 35 to 44 for 16 percent, and those aged 45 and above 4 percent.

The vast majority of suicides occurred among enlisted men at the lower pay grades, said Pearse. Suicides occurred among married men more often than among unmarried men from Fiscal 1998 through 2002. However, unmarried men had a slightly higher suicide rate than married men in Fiscal 2003.

Deployment Raises Suicide Rate

“Suicides among armed forces members deployed to Iraq appear be disproportionately among the youngest soldiers,” Pearse commented. About 64 percent of suicides among those serving in Iraq between April 2003 and September 30, 2004, occurred among 17- to 24-year-olds. This rate was nearly triple the suicide rate for 25- to 34-year-olds, she said.

For comparison, in the five years ending in July 2003, 40 percent of all suicides in the armed forces were committed by 17- to 24-year-olds.

The suicide rate for all service members reached a record high in 1995, prompting each branch of the military to initiate suicide-prevention programs in 1996.

Suicide prevention is viewed as a troop-readiness concern under military doctrine, and suicide-prevention programs were placed under the command of Army and Air Force chiefs of staff and the Navy's chief operations officer, according to the DoD.

The Air Force program, overseen by Chief of Staff Gen. John Jumper, has become a model for other service branches. The 2004 CD-ROM version of the program has two components, one designed for the entire Air Force community and one for the leadership. They both describe signs of distress, encourage people to seek help, and list community resources.

A critical element in the program's success is leadership involvement. The leadership briefing encourages commanders “to create a culture that encourages help seeking and suicide prevention. Suicide is prevented in the unit by addressing quality-of-life concerns on a daily basis.”

Leadership involvement is one of 11 components that make up the Air Force program. The other initiatives include incorporating suicide prevention into military education curricula, providing more preventive mental health services outside of clinical settings, and establishing a psychotherapist-patient privilege for individuals at risk of suicide who are under investigation by central command, Campise said at the conference.

The Air Force program has reduced the suicide rate from an estimated 65 deaths annually in the decade prior to 1996, when the program was implemented, to 33 deaths annually between 1997 and 2003, according to Campise. He emphasized that all of the program's 11 initiatives should be implemented for optimal effectiveness.