Lost in all of the calculations and proposals that accompany debates on remodeling the U.S. health care system is one of its fundamental building blocks—just how many physicians does the country need to serve its residents' health care needs?

Not only must politicians, policymakers, and the medical community determine how many physicians the United States needs, but also they have to make decisions at some point about what types of physicians are needed, how to achieve an optimal distribution of physicians, what can be done to produce a physician workforce that resembles the country's ever-more-diverse demographics, how many international medical graduates should be permitted to practice in the United States, and even if the role of the physician will have to be redefined in the future.

To educate psychiatrists about the intricacies and dilemmas inherent in these issues, Assembly Speaker James Nininger, M.D., devoted several hours of the Assembly's November meeting in Washington, D.C., to workforce issues.

Featured speaker Edward Salsberg, director of the Center for Workforce Studies at the Association of American Medical Colleges, emphasized that in the absence of national- or state-level workforce planning, the system in the United States has been “market driven.” This is not necessarily a negative propellant, but does leave many regions underserved, while others have more physicians than the population needs, he said.

Too much guesswork has been involved in efforts to estimate the ideal number of physicians the United States needs, Salsberg suggested. For example, in the last quarter of the 20th century, there was considerable hand-wringing over predictions that the country was on its way to a physician glut—one that never materialized. Data evaluations conducted in the last several years, however, now foretell a serious shortage of physicians in many specialties, with child and adolescent psychiatry prominent among them.

A web of factors akin to a “perfect storm” has coalesced to increase the demand for more physicians in the next two decades, Salsberg noted. These include immigration-fed population growth, an aging population (the number of Americans aged 66 and older is likely to increase by 35 million between 2000 and 2030), increasing health care utilization rates, economic growth that provides more money to pay for health care, and medical advances that have led to more sophisticated diagnosis and more and better treatments. Mitigating that growing demand somewhat, however, are efforts by government and private payers to cut down on unnecessary procedures and other aggressive cost-containment initiatives.

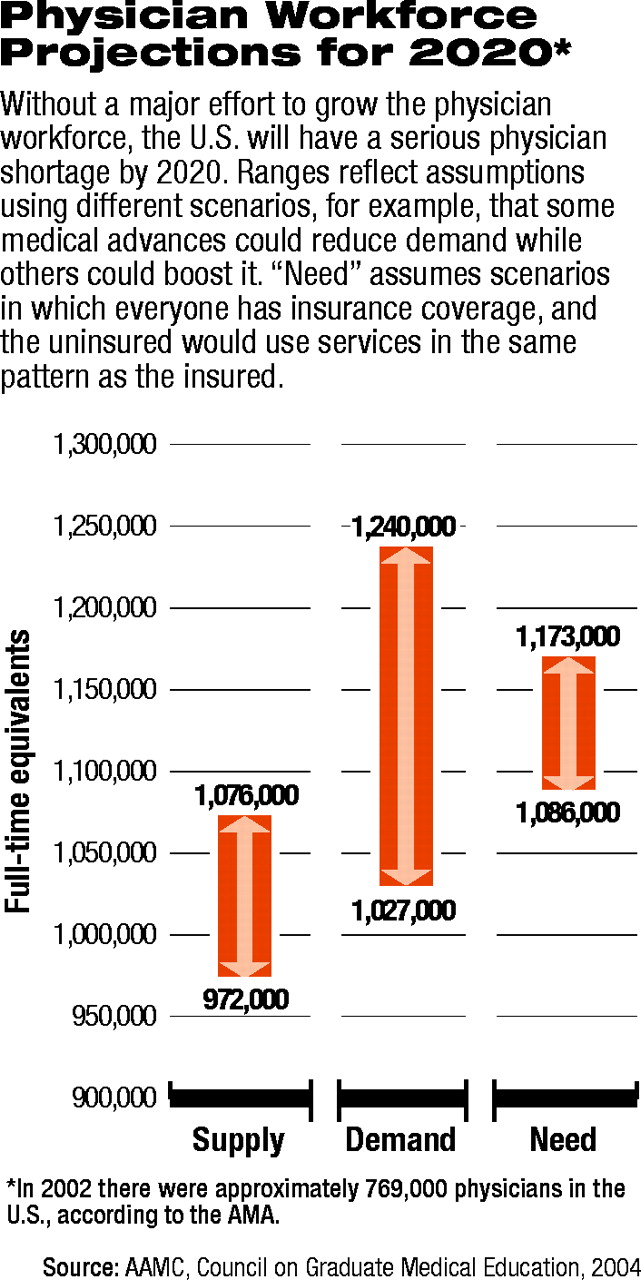

As of 2002, there were about 769,000 physicians practicing in the United States.

Despite that increasing demand, an array of other unfolding trends is likely to tamp down the number of physicians that the nation's medical schools can supply. Like the rest of the population, the physician workforce is aging, and many physicians in the baby-boom era will retire in the next two decades. In addition, younger physicians are making lifestyle choices that include fewer practice hours as they opt to spend more time with their families, Salsberg said, or maintain more control over work time by opting for academic or research careers. The number of U.S. medical school graduates has remained about the same for the last 20 years, he pointed out.

Some of the gap between physician supply and demand will be narrowed by the likelihood that there will be “productivity gains” attributable to technological advances, Salsberg noted, and that the system will make greater use of non-M.D. clinicians such as physician assistants and nurse practitioners. Also, several medical schools are planning to increase the number of students they admit, he added. By 2010 the country's allopathic medical schools are expected to increase enrollment by about 900 a year, or 5 percent, while osteopathic schools plan to add about 900 students by that time, which would be a 30 percent increase.

By 2020, he noted, these increases should lead to a total of just over 1 million physicians, but this is still short of the needed supply.

To reach the number of physicians the country needs two decades from now, strategies will have to be implemented to keep existing physicians in practice. He suggested factors such as more flexible hours and scheduling, improved working conditions, reductions in “administrative and bureaucratic hassles,” devising a solution to the malpractice-insurance crisis, and improving physicians' wages and benefits. Physicians need to convince the public that strategies must address physicians' needs; otherwise, it will become increasingly difficult to find one when they need medical care, Salsberg said.

Without significant increases in projected workforce numbers, Salsberg estimated that by 2020 demand for physicians could outstrip supply by more than 60,000.

As for psychiatry, he noted the severe and growing shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists, which had been predicted decades ago, and urged psychiatry leaders to develop incentives to make the field more attractive to young physicians. There are only about 6,500 child psychiatrists in the United States (out of a total of about 46,400 psychiatrists), according to AMA data cited by APA Medical Director James H. Scully Jr., M.D. The income of these subspecialists has been flat for 20 years, Salsberg said. ▪