Although society may take a dim view of forgetting, doing so could have a“ silver lining”—helping shield a person traumatized by an event from developing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

This notion is suggested by a study conducted by Israeli researchers and published in the May American Journal of Psychiatry.

When a person experiences a traumatic event, he or she is known to be more likely to develop PTSD if certain risk factors are present, for example, preexisting psychiatric illness or physical injury. Several studies have also suggested that recalling the distressing event might be a risk factor for the disorder as well. So Ehud Klein, M.D., chair of psychiatry at Rambam Medical Center in Haifa, Israel, and colleagues conducted a study to determine whether this is the case.

They enrolled 120 individuals who had sustained head injuries and were treated for their injuries at the Rambam Medical Center. Most of the injuries were mild and occurred in traffic accidents.

Each subject was evaluated within 24 hours of the injury with the Memory of Traumatic Event Questionnaire, which these researchers had developed, they noted, since no such tool was available at the time of the study. This nine-item, self-report instrument asked about a subject's memory of the event; where the event took place; who was involved; when it occurred; sights, sounds, and odors associated with the event; things the subject remembered saying during or after the event; and things other people said during or after it.

After the initial assessment, subjects were then assessed one week, four weeks, and six months later for PTSD symptoms. Two instruments were used in the follow-ups—the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale and the Posttraumatic Stress Scale.

The investigators then used the results to determine how well subjects recalled the excruciating events they had experienced and whether their recall could be linked with their subsequent development of PTSD.

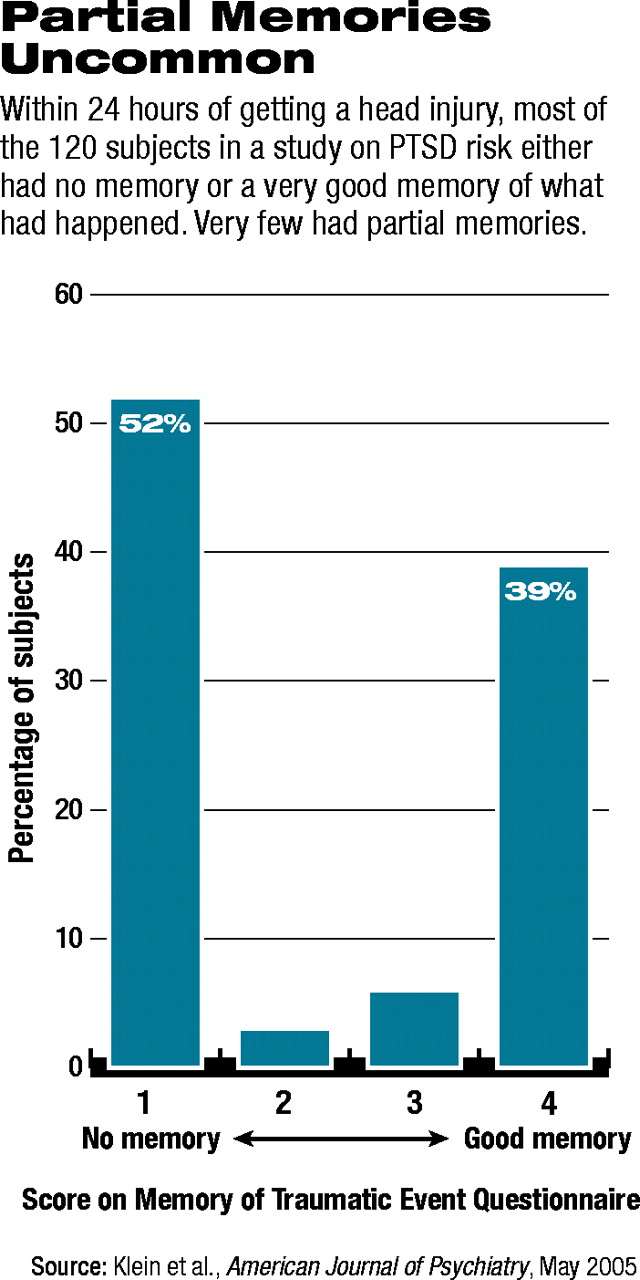

Within 24 hours after injury, the researchers found, 62 (52 percent) of the subjects had no memory of the event; 47 (39 percent) had a very good memory of the event, and 11 (9 percent) had a vague memory of the event. Thus, a bimodal distribution was evident (see chart). Consequently, a categorical approach was taken, with participants divided into two groups, with the median of the questionnaire scale used as the cutoff point. Thus, the subjects were referred to as either “having memory of the traumatic event” or“ having no memory of the traumatic event.” Accordingly, 55 (45 percent) subjects had memory of the traumatic event, and 65 (55 percent) subjects had no memory of it.

Moreover, of the 65 subjects who had no memory of the event, four developed PTSD, compared with 13 of the 55 subjects with memory of the event—a highly significant difference.

“The central finding of our study,” the researchers concluded,“ is that memory of a traumatic event is positively associated with the risk for development of PTSD, while lack of memory of a traumatic event decreases the risk and might, in fact, play a protective role. Thus, along with other factors, such as history of previous trauma, previous psychiatric morbidity, and physical injury, memory of a traumatic event appears to be another risk factor for PTSD.”

Their finding also has a practical implication, the scientists pointed out in their report. Asking patients whether they can recall the event that traumatized them may help identify those at risk for PTSD.

Their results, they added, likewise imply that “`deliberate' disruption of the memory of the traumatic event might prove therapeutically beneficial.” In fact, he and his team are now investigating whether it is possible to facilitate abolition of troubling memories by pharmacological means, Klein told Psychiatric News. And if it is possible, he said,“ we will then study the potential therapeutic benefit of such interventions.”

In view of their finding that recall of a traumatic event may promote development of PTSD, Klein and his colleagues question whether therapies that“ elicit traumatic memories as part of the recovery process”—such as exposure therapy—may be counterproductive in some cases. Nonetheless, a number of studies have found that exposure therapy can help patients with PTSD.

The study was funded by an internal grant from the Rambam Medical Center.

Am J Psychiatry 2005 162 963