The prevalence of suicide-related behaviors has held steady since the early 1990s even though the proportion of people receiving mental health treatment for those behaviors has increased substantially.

This is one of the key findings from a study comparing data from two epidemiological surveys. Study results appeared in the May 25 Journal of the American Medical Association.

Due to the study's design, researchers were unable to determine when respondents received mental health treatment in relation to their experiences with suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

“It is problematic that we have more resources than ever directed at treating mental health problems, but we don't see the prevalence of suicidal behaviors dropping,” said lead author Ronald Kessler, Ph.D., a professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School.

However, it is important to note that the rate of completed suicides dropped by 6 percent in the study by Kessler and his colleagues, or from about 15 suicides per 100,000 people to 14 suicides per 100,000 people, according to Darrel Regier, M.D., M.P.H., director of APA's Division of Research and executive director of the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education. He was not involved in Kessler's study.

Regier noted that a “large proportion of the population with suicidal ideation or attempts may not access treatment” for their symptoms.

“However, if people with severe depression, schizophrenia, and other disorders that place patients at high risk for suicide are receiving more treatment, the drop in completed suicides could be reflective of improved treatment effectiveness.”

Kessler compared data on mental health treatment with data on suicidal ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts for respondents to the 1990-1992 National Comorbidity Study (NCS) and the 2001-2003 NCS Replication (NCS-R).

For the NCS, researchers interviewed 8,098 randomly selected people aged 15 to 54 in their homes. For the NCS-R, 10 years later, they interviewed a separate, randomly selected sample of 9,282 adults over age 18 in their homes.

When Kessler merged the data from the two surveys for respondents in the overlapping age range, he found that there were no significant differences in the percentage of people who had reported suicidal ideation in the prior year. Just 2.8 percent (210) reported experiencing suicidal ideation in the NCS, and 3.3 percent (205) did so in the NCS-R.

Nor were there significant changes in the proportion of people who had a plan to commit suicide during the year prior to the surveys. About 0.7 percent (50) said they had formulated such a plan in the NCS, and 1 percent (63) a decade later.

Among those who made a suicidal gesture—defined as making an attempt that was a “cry for help” but lacked an intent to die—0.3 percent (17) reported doing so in the NCS, and 0.2 percent (12) in the NCS-R.

About 0.4 percent (37) reported making a suicide attempt during the preceding year, the NCS found, and 0.6 percent (47) acknowledged doing so in the NCS-R.

When he analyzed the number of respondents who reported receiving any type of treatment “for emotional problems” during the prior year, he found that for those with certain suicidal behaviors, the number who received treatment rose dramatically during the 1990s.

For instance, among those who said they had made a suicidal gesture, the NCS found that 40.3 percent received mental health treatment in the early 1990s. A decade later, that percentage had risen to 92.8 percent, according to the NCS-R.

Researchers did not determine when the respondents received treatment in relation to experiencing suicidal thoughts or exhibiting suicidal behaviors.

For respondents who made a suicide attempt, 49.6 percent reported having received mental health treatment in the first survey, and 79 percent did in the second survey.

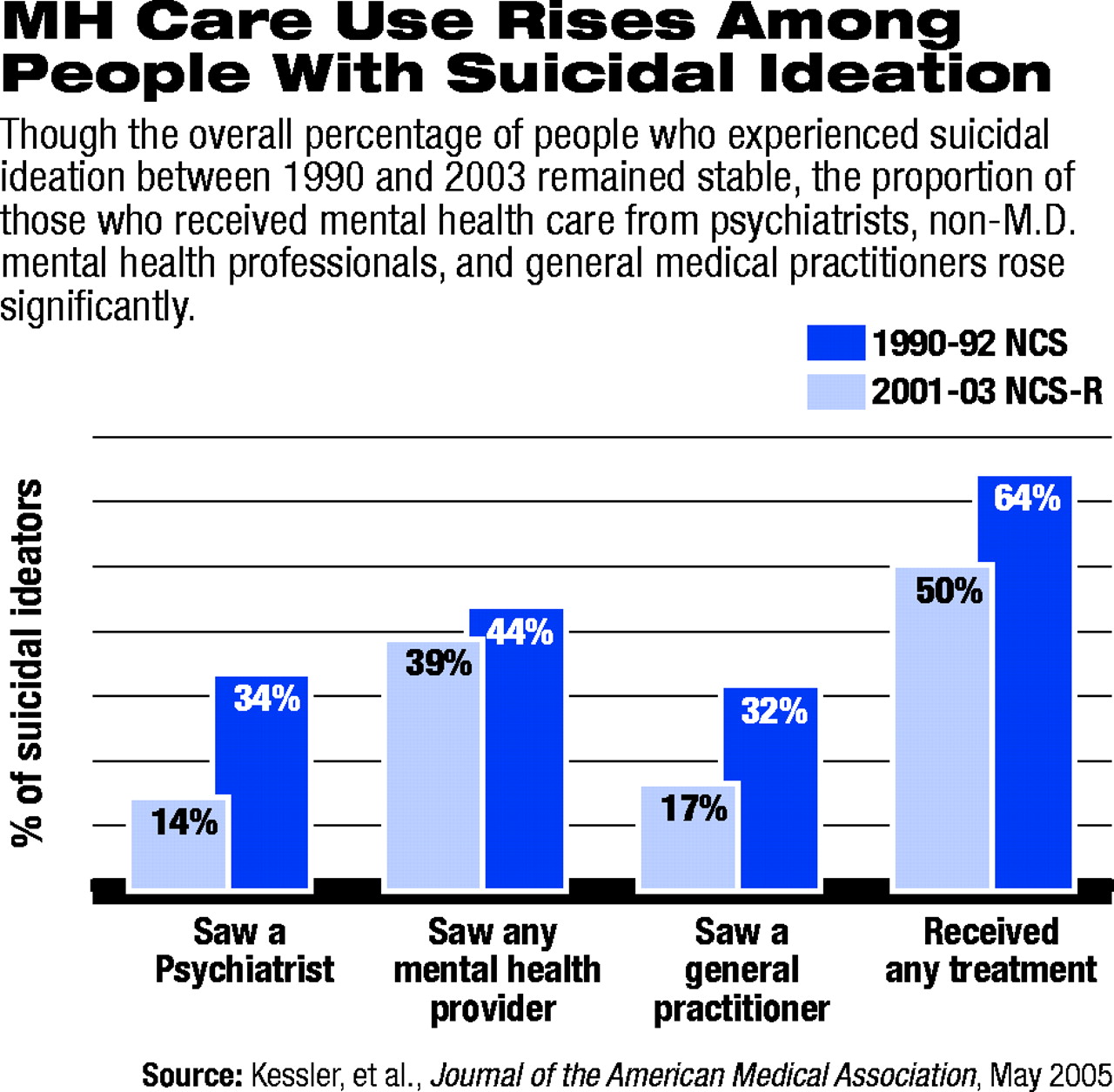

The proportion of people with suicidal ideation and behavior who sought treatment from psychiatrists in particular rose throughout the 1990s.

Among those with suicidal ideation but who did not make a suicidal gesture or attempt, the NCS found that 14.4 percent saw a psychiatrist during the prior year, while 33.5 percent did so in the NCS-R.

Among those who reported making a suicidal gesture, 13.4 percent reported seeing a psychiatrist in the preceding year in the NCS, while 42.8 percent did so a decade later in the NCS-R.

There were also substantial increases in the proportion of respondents with suicidal ideation and behavior who reported seeing a general medical practitioner for mental health problems from the first to the second survey. Kessler attributed the increase in visits to psychiatrists and general medical practitioners in large part to “the introduction of direct-to-consumer marketing of psychotropic drugs.”

He said he could not explain the discrepancy in the increase in mental health treatment among people reporting suicidal behaviors and the failure of those behaviors to decrease during the same period.

Because he could not determine whether the respondents received treatment before or after becoming suicidal, Kessler said he was unable to conclude that they didn't get treatment in time to prevent an attempt, or if they did get treatment in time, whether it was ineffective in preventing suicide attempts.

“Both processes could have been at work,” the authors wrote.

Kessler and his colleagues called for an increase in the number of programs that emphasize suicide prevention and “timely treatment seeking, specifically among people with suicidal ideation.”

They also acknowledged that “recognition is needed that effective prevention of suicide attempts might require substantially more intensive treatment than is currently provided to the majority of people in outpatient treatment for mental disorders.”

JAMA 2005 293 2487