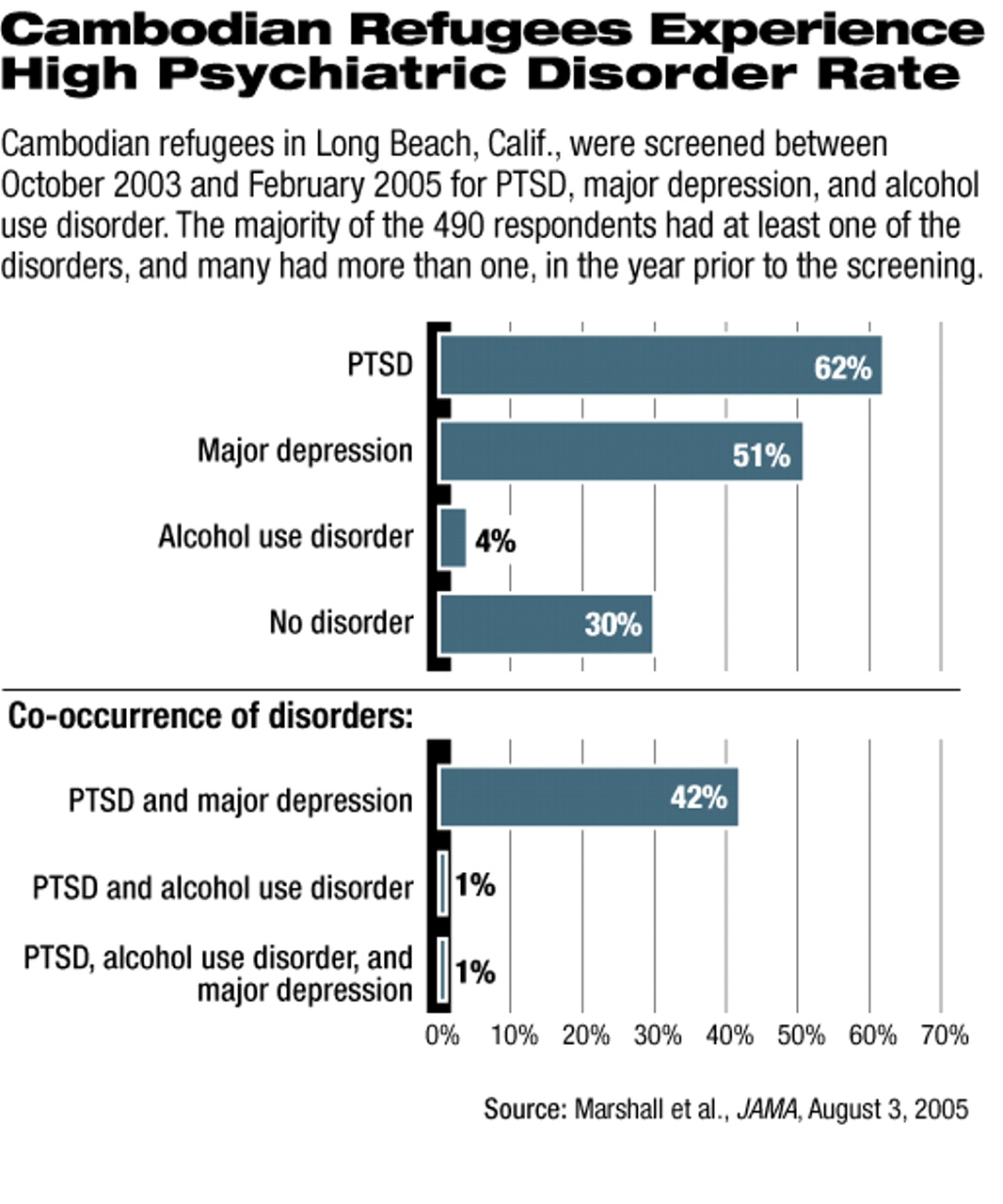

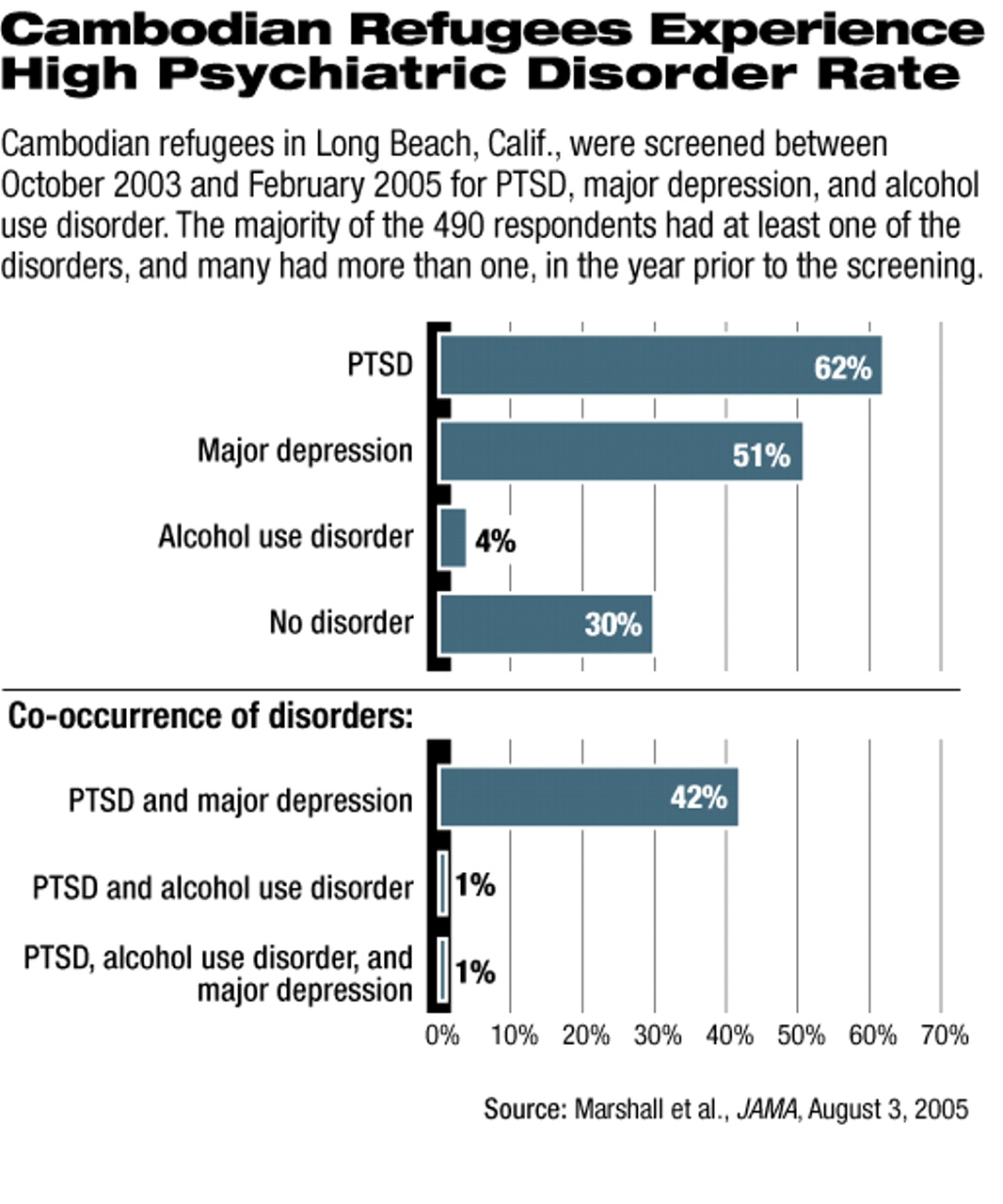

It turns out that time does not heal all wounds, as evidenced in a recent study of the mental health of Cambodian refugees who came to the United States more than 20 years ago. All of the nearly 500 study participants had been exposed to trauma prior to immigrating to the United States, and 62 percent of them are suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) two decades later.

Depression rates were also alarmingly high, with 51 percent showing symptoms warranting a depression diagnosis. These rates for the two disorders“ are extremely elevated” compared with the general U.S. population's rates, said the researchers.

The results of the study are published in the August 3 JAMA.

Researchers at RAND Corp. and California State University at Long Beach enrolled a stratified random sample of Cambodian refugees living in Long Beach, Calif., which has the largest population of Cambodians in the United States. Participants were between the ages of 35 and 75 and had lived in Cambodia during the brutal Khmer Rouge regime in the middle and late 1970s, when about 2 million of their countrymen were killed by the Khmer Rouge.

Trauma prior to arriving in the United States was assessed with the 17-item Cambodian-language version of the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire. Almost all of the participants had endured multiple traumas, with at least 90 percent reporting nearly dying from starvation, being in combat, having family or friends murdered, and witnessing killings or beatings; 54 percent had been tortured. The mean number of reported traumas per individual was 15.

Subjects also completed the Survey of Exposure to Community Violence, which was used to determine whether they were victims of violence after coming to the United States, and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) version 2.1, which was used to evaluate them for PTSD and depression. The CIDI reflects DSM-IV diagnoses, the researchers noted. In addition, subjects were screened for alcoholism with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

All interviews were conducted in Khmer, the subjects' native language, since only a minority were fluent in English.

The research team, headed by Grant Marshall, Ph.D., of RAND noted as well that their study population was generally of “low socioeconomic status, with low levels of education, English-speaking proficiency, and employment.” Nearly 70 percent had household incomes below the federal poverty level.

While the Cambodian immigrants showed very high levels of both PTSD and depression, only 4 percent had symptoms of an alcohol-use disorder. Alcohol-use disorders were “significantly associated only with exposure to trauma after immigration to the United States,” not with having PTSD or depression, the researchers reported.

The data on participants' exposure to trauma once they had come to the United States indicated that 34 percent had seen a dead body in their neighborhood, 28 percent had been robbed, and 17 percent had been threatened by a weapon. Overall, this group had been exposed to a mean of 1.7 types of trauma out of a list of 11 such events.

The data led the researchers to conclude that “members of refugee communities can have substantial need for mental health services even years removed from their tribulations.” They noted that many refugee studies have focused on PTSD, but “the relationship of trauma to depression has perhaps not been as widely appreciated.”

Of particular interest, the researchers noted, is that women in this population were no more likely to develop PTSD or depression than were men, a finding that runs counter to other studies of these disorders. “One possible explanation,” they wrote, “is that the frequency or severity of the traumas differed for men and women in ways not captured by our trauma measures.” They urged additional research on this topic.

Marshall and his colleagues noted that while previous data have demonstrated a high level of psychiatric disability in refugee populations, theirs is an important contribution to this literature because of the population studied. Most previous data come from individuals who had sought health or social services, which may have led to the overestimation of mental health problems, or from studies of asylum seekers, “who may be motivated to overreport psychiatric symptoms.” They pointed out that using a general population of refugees is likely to give more accurate data on their health status, “guiding health-policy decision makers to the needed services for this refugee community.”

JAMA 2005 294 571