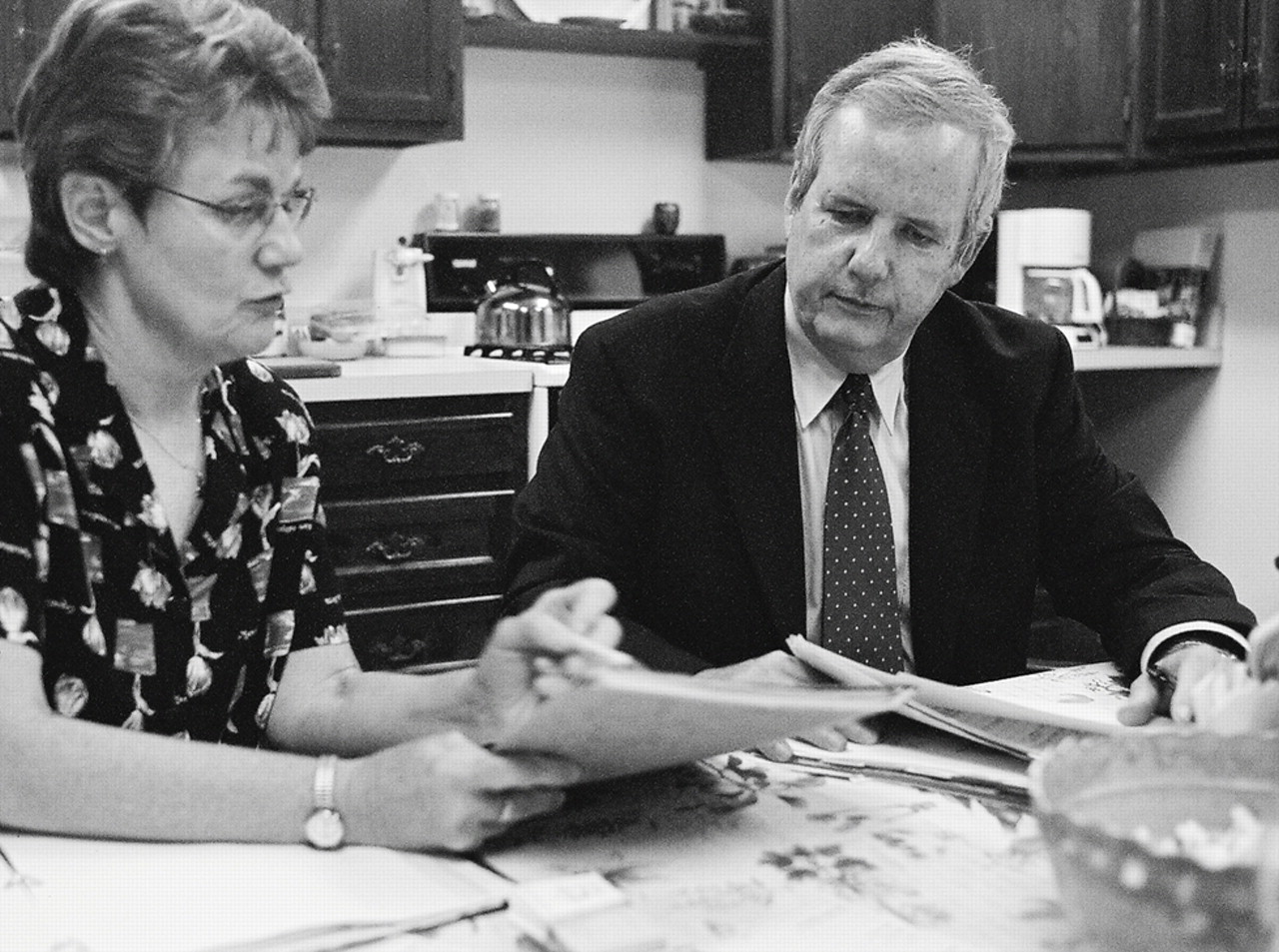

Ignoring both the nurturing smell of fresh popcorn and the half-dozen other people crowded around the kitchen table, Sarah Armstrong, M.D., concentrates on the chart before her, thumbing through the thick loose-leaf notebook, occasionally adding her own observations about the patient to the orange pages.

“She was definitely on the edge last week, not realistic,” Armstrong says to John McIntyre, M.D., tonight's attending psychiatrist.

“What are your thoughts?” asks McIntyre, in his best Socratic manner.

“Better to take an attending in to see her tonight,” says Armstrong.

Armstrong is a second-year psychiatry resident at the University of Rochester. McIntyre is head of psychiatry and behavioral health at Unity Health System in Rochester, N.Y. Tonight is a Thursday, which means they are volunteering at the St. Joseph's Neighborhood Center, a free clinic for the uninsured, located in a pair of connected, renovated houses between rundown and up-and-coming areas of Rochester.

McIntyre alternates between seeing patients in small but comfortable consulting rooms and reviewing charts with one of the two residents who are on duty this evening. A volunteer nurse keeps everyone on schedule. Their meeting place is the center's second-floor kitchen. Residents and medical students scribble in charts. The bowl of microwaved popcorn, replenished regularly, rests in the center of the table.

For people with little or no insurance, the oddly shaped yellow building (created by uniting two freestanding houses) across the street from a soup kitchen represents their last hope for health care. For volunteer doctors, including seven psychiatrists, the free clinic at the St. Joseph's Neighborhood Center offers a way to serve their community and practice medicine without much of the bureaucratic burden of contemporary health care.

Less Bureaucracy, More Care

“The volunteers are the heart of the system,” said clinic director Sister Christine Wagner, S.S.J, Ph.D., of the 140 doctors, residents, nurses, therapists, and lay volunteers who keep the center running.“ They recruit themselves. They get enthusiastic and talk to their colleagues.”

“Free clinics fill a gap in our nonsystem of medical care,” said McIntyre, a former APA president, in an interview at the clinic.“ Where do the 45 million people without health insurance go for care? They go to emergency rooms or other places that are not good for longer-term, consistent care.”

Thursday is psychiatry night at St. Joseph's. An experienced attending psychiatrist joins with a resident from the University of Rochester Medical School and an occasional medical student on psychiatric rotation. Allied health students from other area colleges volunteer at St. Joseph's as well.

The St. Joseph's Neighborhood Center opened in 1993, an outgrowth of the homeless shelter still located across the street. The center is run by the Sisters of St. Joseph, a Catholic order founded in France in 1650. The sisters of the Rochester congregation (as the local community of the order is called) took over an old house and rehabbed it with the help of family and friends.

“I learned more about drywalling than I'll ever need to know,” said Sister Sheila Briody, S.S.J., D.Min., the center's director of counseling.

Most patients are working people who do not have health insurance or who have lost their jobs and do not qualify for Medicaid or Medicare. “These are people who have had the door shut in their face,” said Briody in an interview. “They don't fit into the system. They have no job, no insurance, and no access to care.”

The center's mission is to offer health care to people who do not have health insurance, either public or private. In addition to medical and dental services, the center provides counseling services and referrals and is involved in social service advocacy. The center has only seven employees and is funded solely by grants.

“We work to maintain a holistic approach to physical and mental health, especially with a population living in a culture of poverty,” said Wagner. “It's like a circle. You can enter anywhere and move where needed.”

In its early years, Quinton Schubmehl, M.D., a retired psychiatrist, volunteered his services. But after he died, the sisters spent years looking for a replacement. Eventually Rory Houghtalen, M.D., then residency training director at the University of Rochester Medical School, spotted an appeal in a newsletter of an APA district branch, the Genesee Valley Psychiatric Association.

“I answered a personal ad from a nun,” joked Houghtalen, in an interview. He was looking not only for a volunteer opportunity but also for a way to get residents involved in community service. It took him eight months to persuade the university to extend liability coverage for residents working at the center and set up the program as an elective. Ultimately, one or two residents and one attending psychiatrist rotated coverage on Thursday evenings. Without the paperwork and bureaucracy found in hospitaland state-run clinics, they could spend more time treating patients or supervising. Today, seven psychiatrists—including Schubmehl's son John—serve at the clinic.

“The biggest administrative problem is trying to figure out how to give residents academic credit for their rotation in the clinic,” said Houghtalen, who left the university in 2002 and is now medical director for education at Unity Health Services in Rochester. “We've set it up as an elective, and I do a formal evaluation, but they don't get the credit hours for service—possibly because at the university, the university can bill for their hours, which they can't do for their work here.”

Most free clinics serve the homeless population, he said, who are more likely to have persistent, serious mental illness.

He noted that there are fewer no-shows for appointments at the clinic than at the university. He estimates that the no-show rate of 12 percent to 15 percent at St. Joseph's is half that at the university. Everyone interviewed for this article chalks that up to patients who appreciate the center's presence and the care they receive.

“There's no resentment,” said resident Scott McMahon, M.D.,“ They know we're here to help them.”

Clinic Has Wide-Reaching Benefits

“Coming here was the best thing that ever happened to me,” agreed Jeremy S., a clinic patient diagnosed seven years ago with panic disorder. “Everyone here is kind and supportive. They're not just here to take your money. I trust the doctors because they want to be here.”

It is also a gratifying experience for the residents, said Houghtalen.

“They have their own group of patients they see over time and an experienced faculty member to consult with about a diagnosis. It's a setting they don't have elsewhere in their training. They have an opportunity to see patients who are different from those seen at the university. Patients [seen at the university] have more comorbidities, more social dislocations, and more difficulties in compliance.”

There's something else, too.

“This is how I envisioned practicing medicine when I went into medical school,” said McMahon, who switched to psychiatry after a year in an anesthesiology residency. (“It was like working in a chem lab,” he said.)

“It's hard to evaluate someone in 15 minutes,” he said.“ Most patients need more time. There are layers of things to discuss, and here we have the opportunity to discuss them, not just put out fires.”

Maintaining continuity of care challenges these willing part-timers. The attendings and residents discuss that issue directly with patients, some of whom agree to visit monthly, while others agree to be seen between regular visits by another psychiatrist. To ease communication among staff members, Houghtalen worked with former chief resident Craig Schoenecker, M.D., to improve the templates used to record quality progress notes and give any clinician up-to-date information on the patients.

Finding malpractice coverage for work at free clinics is another issue for all free clinics. Charitable immunity protection legislation (not to be confused with “good Samaritan” laws) in some states can help. Congress provided some malpractice protection in 2004 through the Federal Tort Claims Act, but only for clinics that offer completely free services. Places like St. Joseph's, which ask for modest fees from patients who can afford them, are excluded.

New York lacks a charitable immunity law, but most of the physicians at St. Joseph's have been able to convince their employers to extend coverage for their work at the clinic. One psychiatrist who has not pays several hundred dollars a year out of his own pocket. Around the country, many retired doctors who would like to volunteer must overcome both malpractice and licensing hurdles.

About two-thirds of all U.S. physicians offer some form of charity care, reducing or eliminating charges to patients who can't afford needed services, according to a 2002 report by the American Medical Association. Among specialists, psychiatrists offer charity care most often (73.3 percent), closely followed by general surgeons and internal medicine specialists. How much of this care is provided in offices or hospitals and how much in free clinics is unclear.

Even the number of free clinics is unknown, although Janet Walton of Volunteers in Health Care, a national resource center for organizations providing health care to the uninsured, estimates that there are about 1,000. Their size, purpose, and patient population vary almost as much. Free clinics may run on a shoestring or be multimillion-dollar operations (see box on

page 7).

St. Joseph's has an annual budget of $450,000. The clinic's biggest problem is finding resources for services it can't provide. “When someone needs a surgery, a scan, or an inpatient placement, we hit our limits,” said Wagner. The next step in those cases means connecting with other community resources.

The clinic does provide free medications to patients from a drug cabinet stocked with samples from pharmaceutical sales representatives.

“A lot of partners have to converge to sustain the clinic, and one of them is pharma,” said Houghtalen. “There's a lot of appropriate concern about pharmaceutical companies, but most industry reps have been faithful in supplying samples and helping with indigent programs.”

Wagner is grateful for all the volunteer help, but now she wants to step back and work on the bigger health care picture.

Continued growth has its own contradictions, she said: “Expanding the clinic would mean shoring up a broken system. You do not solve the health care problem on the backs of volunteers.”

She has begun conversations with city leaders and Blue Cross officials about why people are falling through the cracks. While she doesn't advocate any specific system, she said it's time to consider universal access.

“We'll know we've been successful when we can close,” she said.

Information on St. Joseph's Neighborhood Center is posted at<www.volunteersolutions.org/uwgr/org/219071.htm>. Information on volunteering at free clinics is posted at<www.volunteersinhealthcare.org/pdfs/FCcontactlist.pdf>.▪