After facing tremendous adversity in the days following Hurricane Katrina, for some Gulf Coast evacuees who arrived in Washington, D.C., last month, psychiatrists were the true heroes.

Two planeloads of survivors fleeing the devastation—about 250 people—arrived at the D.C. Armory on September 6.

Among them were people who had witnessed brutal violence while waiting to be rescued at the New Orleans convention center or Superdome, gone without food and water for days, and had lost family members to the flood that followed the storm.

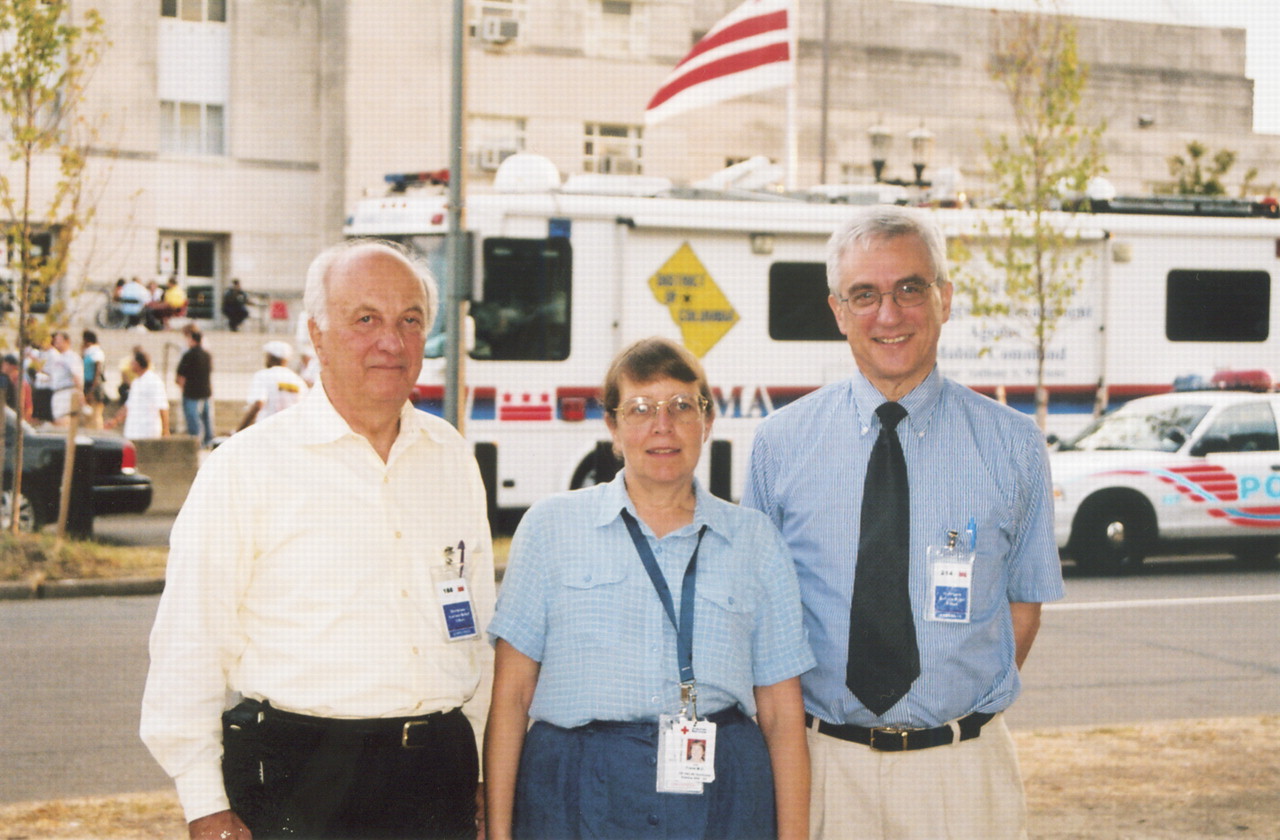

Steven Steury, M.D., who is chief clinical officer of the D.C. Department of Mental Health (DMH), told Psychiatric News that upon arrival, many evacuees were “delighted to finally have a clean, safe, and welcoming place to live” and that it took several days before people began to experience symptoms related to their distress, including anxiety, insomnia, and tearfulness.

“Some, but not all, were interested in talking about their experiences immediately,” Steury said.

He noted that soon after arriving at the armory, “those with more resources and resiliency” left to reunite with family and friends. Others received housing vouchers and were moved to apartments and houses around the metropolitan area.

By September 20, 140 evacuees remained; a week later, there were fewer than 100.

The DMH took the lead in providing psychiatric services to the evacuees and worked with volunteer faculty and residents from area medical schools and hospitals, including Howard University, George Washington University, Georgetown University, St. Elizabeths Hospital, and Children's National Medical Center.

In addition, private-practice psychiatrists who were members of the Washington Psychiatric Society (WPS) also volunteered their services.

WPS President David Fram, M.D., toured the armory and observed that“ the mental health services available had been designed to provide immediate service and at the same time minimize the development of longer-term trauma problems.”

He also found that the shelter “was well-organized and able to provide needed structure for the evacuees, whose lives had become so very disrupted.”

Psychiatric `First Aid' Emphasized

Among the original group were about 15 evacuees who needed treatment for psychotic disorders, including a young man experiencing his first manic episode, Steury said. Some had been without their medications for days, and others had never been treated, he said.

Psychiatrists hospitalized some of the evacuees with psychosis and treated others at the DMH's Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Program just a few blocks away. Others were treated on site.

Julia Frank, M.D., who coordinated the volunteer efforts of psychiatrists at the armory, noted that “addressing the needs of the psychotic evacuees so that they are able to more quickly act like everyone else” was a major first step in reducing stress levels.

Frank is director of medical student education and an associate professor of psychiatry at George Washington University and is the WPS representative on disasters to APA.

Nonpsychiatric mental health professionals working with the DMH, Red Cross, and Strong Families Program, which falls under the umbrella of the D.C. Department of Human Services, offered the bulk of the “psychological first aid” to evacuees, Frank said, and notified psychiatrists when they identified those in need of more specialized help.

Clinicians who conduct psychological first aid ensure that a person exposed to a disaster is safe and feels safe and and that basic needs such as food, water, and shelter are met. Clinicians may also help victims reunite with loved ones and provide them with information about what to expect of themselves in the near future, Frank said. The aim is to instill a sense of calm, connectedness to others, and hope in the person who is experiencing distress.

This means that clinicians do not “debrief” survivors or force or encourage them to discuss traumatic events. “We teach people that symptoms like sleeplessness and anxiety can be expected but will not necessarily continue forever,” she said.

Frank and Steury were especially attentive to evacuees who endured serious losses, such as the death of a family member, and who may be struggling with continuing or worsening symptoms. “We make sure they know they can get help” in these circumstances, she said.

As the evacuees are moved to housing throughout the D.C. area, some will continue to receive mental health services through the DMH.

Work Takes Toll on Psychiatrists

Psychiatrist Ike Nnawuchi, M.D., realized that the long hours he spent with survivors of Hurricane Katrina were taking a toll on him when he noticed how relaxed he was while back at his regular job at the DMH's Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Program. There, though many patients are psychotic, agitated, or both, “I felt like I was on vacation in the Bahamas,” he told Psychiatric News.

When he spoke to psychiatrists and mental health professionals volunteering at the armory, many told him they felt more fatigued than usual, but weren't sure why. “It was the intensity of the stories we were hearing,” he said.

On many occasions, the evacuees' stories shocked and saddened him (see story at bottom of

page 9). For instance, one man witnessed the suicide of a New Orleans police officer. “He also saw shootings and stabbings occurring around the convention center,” Nnawuchi said.

The same man told Nnawuchi that he saw a woman swimming through deep water with two of her young children. As she struggled, “he could tell that she was trying to decide which one to leave behind” so she could save herself and her other child, a toddler. After she let go of her 4-year-old, the man swam over and rescued the older child.

After they spoke, Nnawuchi learned that the man had been crying each day, in private, and rarely slept. Nnawuchi prescribed medication to alleviate his insomnia and also prescribed an antidepressant.

Steury, too, has been impacted by his work at the armory. Though he was far removed from the first responders in New Orleans, he said he felt tense and experienced mild insomnia during his first week of work at the armory.

He noted that many of the evacuees had difficult lives and were experienced at overcoming adversity. “It's been a very moving and important experience to work with so many resilient people with such awful and life-threatening experiences,” he said. ▪