Researchers' conflicts of interest appear to be prevalent in psychiatric clinical trials and associated with a greater likelihood of reporting a drug to be superior to placebo, according to a review of such trials.

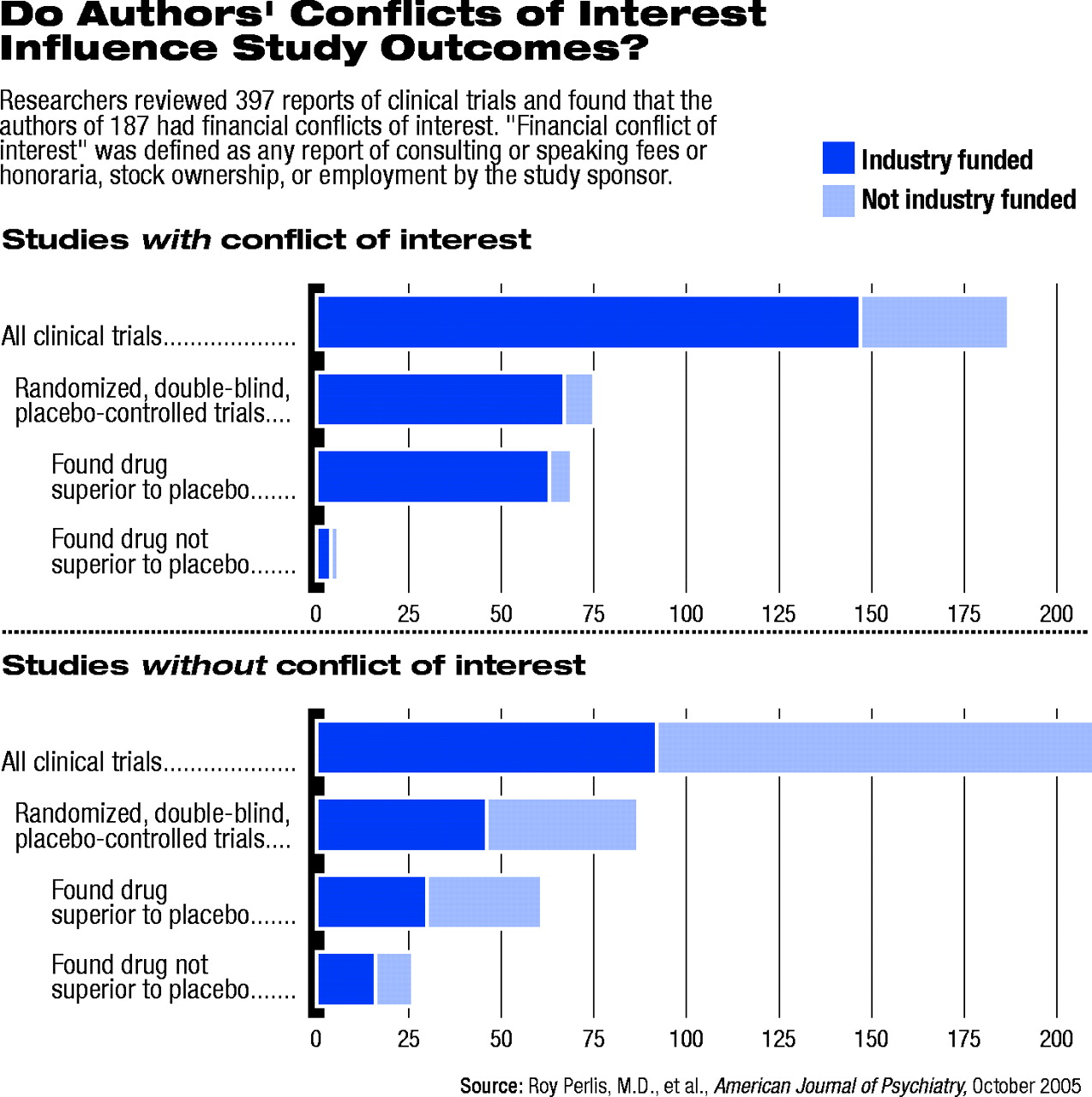

Among 397 psychiatric clinical trials identified, the authors found 239 (60 percent) reported receiving funding from a pharmaceutical company or other interested party. The review, published in the October American Journal of Psychiatry, found that 187 studies (47 percent) included at least one author with a reported financial conflict of interest.

“I was interested in knowing where these randomized, controlled trials that we depend on when we write our treatment guidelines were coming from and who pays for them,” said Roy Perlis, M.D., the study's lead author. “It was more curiosity than anything else.”

Perlis, an instructor in psychiatry at Harvard Medical School who previously performed a similar analysis and found similar results in the dermatology literature, said the percentage of authors who reported a conflict of interest or a competing interest is similar to rates reported in the general medical literature. The author conflict rates in previously studied areas of medicine generally range between 30 percent and 50 percent of authors, which leaves psychiatry at the higher end of the number of author conflicts.

Perlis said that the higher rates of conflict of interest in psychiatry did not surprise him because of the growing number of new drugs entering the psychiatric field in recent years, resulting in many large clinical trials.

He said that industry involvement and collaboration with researchers have a largely positive impact on psychiatry. His past research collaboration with the pharmacological industry is part of what led him to seek to understand the implications of that collaboration.

“We need to work with industry. [Pharmaceutical companies] are the ones with the drugs. They are the ones with the resources to study the drugs,” he said. “But because I was doing this kind of work, I wanted to understand what it meant, how it might influence me, how it might influence my work.”

The review was based on a MEDLINE search of articles published between January 2001 and December 2003 in the American Journal of Psychiatry, Archives of General Psychiatry, Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, and Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. The journals were selected as the most widely cited general psychiatric journals that publish clinical trials.

The source of study funding, as well as potential author financial conflicts of interest, were determined by published disclosures. The researchers defined author financial conflict of interest as any report of consulting or speaking fees or honoraria, stock ownership, or employment by the study sponsor.

The impact of financial conflicts of interest among medical researchers has raised concerns among physicians and in the general media, among others. However, the prevalence and implications of conflict of interest in psychiatry have received little attention, apart from occasional editorials.

The dearth of conflict-of-interest research in psychiatry is especially important, according to the study authors, due to the extent of industry involvement in drug development in psychiatry, the rapid growth in FDA-approved pharmacotherapies in psychiatry, and recent calls for the establishment of a clinical-trial registry to report the results of all clinical trials, regardless of outcome.

The review found that among the 162 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies examined, those studies with authors reported to have conflicts of interest were 4.9 times more likely to find positive results for the intervention. The association was significant only among the subset of studies funded by the pharmaceutical industry.

The review was limited, Perlis said, by an inability to explain the link between conflict of interest and positive studies. Although it found an association, more research is needed to identify why that association exists.

Perlis said some plausible explanations make the link between drug-industry involvement and positive study outcomes “perfectly reasonable.”

One explanation is that the pharmaceutical industry's access to greater resources allows researchers to conduct bigger studies, which are more likely to eliminate random variables. Those same substantial resources allow for better-designed studies, also more likely to yield a positive result.

“But there are also potentially less-good reasons for the relationship between conflict of interest and a positive trial that we need to understand,” Perlis added.

The Perlis-led review should encourage organizers of a planned clinical-trial registry and the companies weighing their participation in it to continue moving forward, he said.

The review raises questions, Perlis said, regarding the appropriateness of 60 percent of the medical specialty's randomized, controlled trial results originating from industry-funded studies.

Some may see the government-sponsored Clinical Antipsychotic Trial of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study that compared the effectiveness of five drugs among 1,493 schizophrenia patients at 57 medical centers as a better model for future drug studies (see

page 1).

That study, which was released in September, was the type that could only have been done with federal government support, because no single company would have the incentive to do it, he said.

“Companies conduct trials in general because they are interested in marketing their drugs. That's not bad—it's just the way businesses work,” he said. “But as clinicians and researchers, we often have different goals.”

A question Perlis said he hopes his analysis leads researchers and physicians to answer is the extent to which the federal government—and not industry—should fund clinical-trial research.

Am J Psychiatry 2005 162 1957