A nationwide survey of U.S. public schools found that 87 percent of schools made mental health services available to all students.

An average of 20 percent of students at each school received some type of school-supported mental health service in the school year prior to the report.

The study, “School Mental Health Services in the United States, 2002-2003,” surveyed a nationally representative sample of the country's approximately 83,000 public elementary, middle, and high schools. The study was conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to provide baseline information on the “characteristics of mental health services provided in U.S. schools.”

“Taking action to address childhood mental health problems now can save lives, especially when school personnel work with parents to identify children and intervene appropriately before they develop significant problems,” said SAMHSA Administrator Charles Curie, M.A., in a statement describing the reasons behind the survey.

Eugenio Rothe, M.D., chair of the APA Corresponding Committee on Mental Health and the Schools, said the most important point of the study is that it shows schools, not pediatricians, are the frontline providers of mental health care for children.

“That is something that dispels a myth, and I don't think we have been paying enough attention to the school situation,” Rothe said.

The report found that more than 80 percent of schools provided assessments for mental health problems, behavioral management consultation, and crisis intervention, as well as referrals to specialized programs. A majority also provided individual and group counseling and case management.

Almost half of the school districts (49 percent) contracted with community-based individuals or organizations to provide mental health services to the students. County mental health agencies were the most frequently reported type of community-based provider.

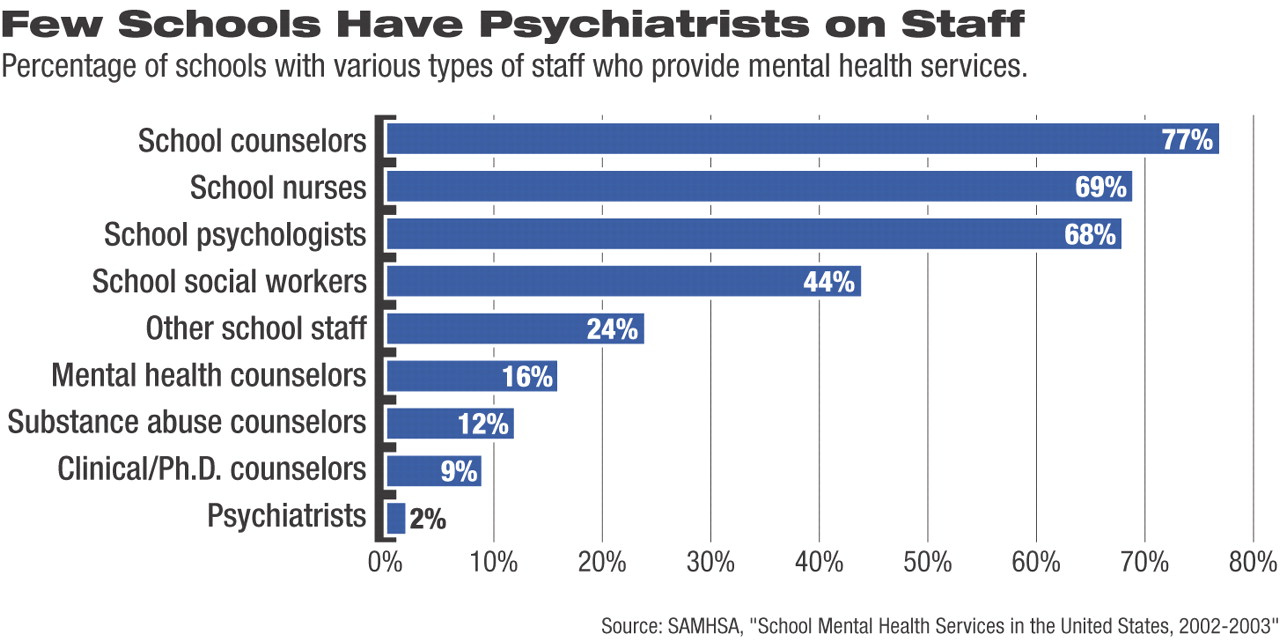

Rothe said he was concerned about the survey finding that the vast majority of mental health services were provided by nonmedical mental health clinicians, while many of the conditions identified appeared to be medically related. The report found that school counselors were the most prevalent mental health providers and present in 77 percent of schools, while psychiatrists were the rarest type of clinician, providing services in only 2 percent of schools.

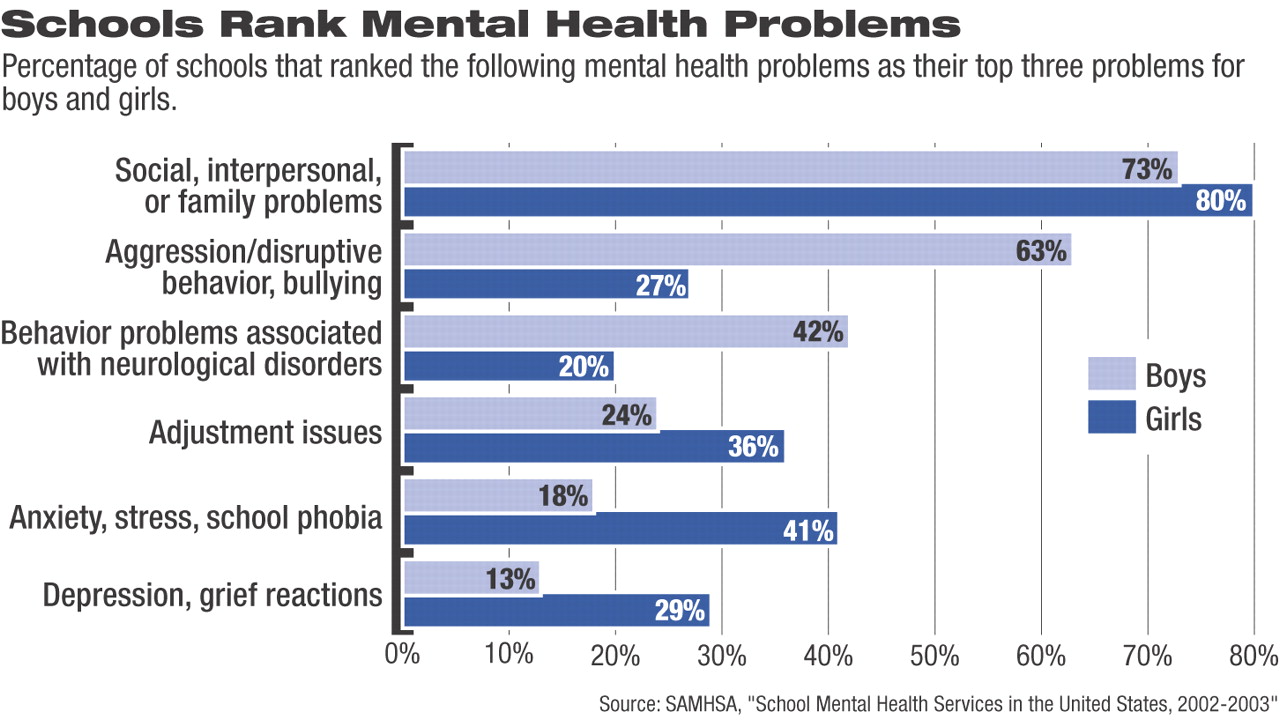

Among mental health disorders or symptoms identified by the study, aggression or disruptive behavior and behavior problems associated with neurological disorders were the second and third most frequent problems among boys. Anxiety was the second most frequent problem among girls. The leading mental health problems among both sexes were social, interpersonal, and family problems.

“So what we are seeing is that way up there on top of the reasons for referral are conditions that need to be treated with medications,” Rothe said. “The problem is that psychiatrists are largely being left out of the picture.”

The study illustrates that there are many variations in how psychiatrists are received by school systems across the country. One of the main reasons psychiatrists are infrequently utilized is funding limits, Rothe said. But there are varying degrees of stigma toward psychiatry in different parts of the country. Sometimes, psychiatrists are seen as individuals who are going to medicalize problems that the school wants to address at a less-intense level.

Rothe, who has worked with Dade County, Fla., public schools for over 15 years, said psychiatrists need to develop strategies for becoming more engaged with the public schools and see their local school system as the front line for the provision of mental health services for children.

The ways psychiatrists can successfully become involved with their local school systems varies tremendously from one region to another. A good example of one way to connect to schools, Rothe said, is the APA Alliance's“ When Not to Keep a Secret” contest, which solicits essays from high school students as a suicide-prevention technique and introduces students to mental health issues in a nonthreatening manner.

Darcy Gruttadaro, director of the Child and Adolescent Action Center at the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), said the study is very helpful in providing a better national picture of the role that schools are playing in the delivery of mental health services. However, the study is limited because it depends on schools to gauge their own performance. Future research in this area would benefit from a related survey of families or another tool to gather“ the family perspective.”

The study highlights how important it is that services delivered in schools have a solid research base.

NAMI is pilot testing a national school-based mental health education program to help school professionals understand the early warning signs of mental illness in children.

The survey results are posted at<www.mentalhealth.samhsa.gov/publications/allpubs/sma05-4068/>.▪