In fall 2003 a Catholic nun named Antonnette Carbon started a small mental health clinic outside of Ayacucho, Peru. Ayachucho is a remote city in the high Andes. Its population is poor. Furthermore, Ayacucho was the cradle of a terrorist movement during the 1970s and 1980s and of government reprisals during the 1980s and 1990s. Thus, many of its residents were victimized by both terrorists and the Peruvian military and consequently experienced posttraumatic stress disorder.

Carbon, who hailed originally from the Philippines, had a strong background in psychiatric nursing. She launched the clinic with just a smattering of medication samples and a local nursing staff that was entirely voluntary. She also had the help of a volunteer psychiatrist from Lima, Luis Matos, M.D.

Around this time, two Connecticut psychiatrists—Mark Rego, M.D., and James Phillips, M.D.—happened to see an ad in the physician leisure magazine Diversion. The ad said that the Peruvian American Medical Society (PAMS) was looking for psychiatrists to join their mission in Peru.

Rego and Phillips had been wanting to do volunteer work in an underserved, developing country for some time, although each had a private practice and also a position at Yale University. Moreover, both Rego and Phillips spoke Spanish fluently. “So we called the number in the ad,” Rego said,“ and signed up.”

So did Nora del Busto, M.D., a Peruvian-American child psychiatrist at Wayne State University and a longtime PAMS member.

Ralph Kuon, M.D., a Peruvian-American cardiovascular surgeon from California, had been organizing the general PAMS medical mission to Ayacucho for the past 10 years and was the person who initiated the ad for psychiatric involvement. He was delighted to have Rego, Phillips, and del Busto come on board.

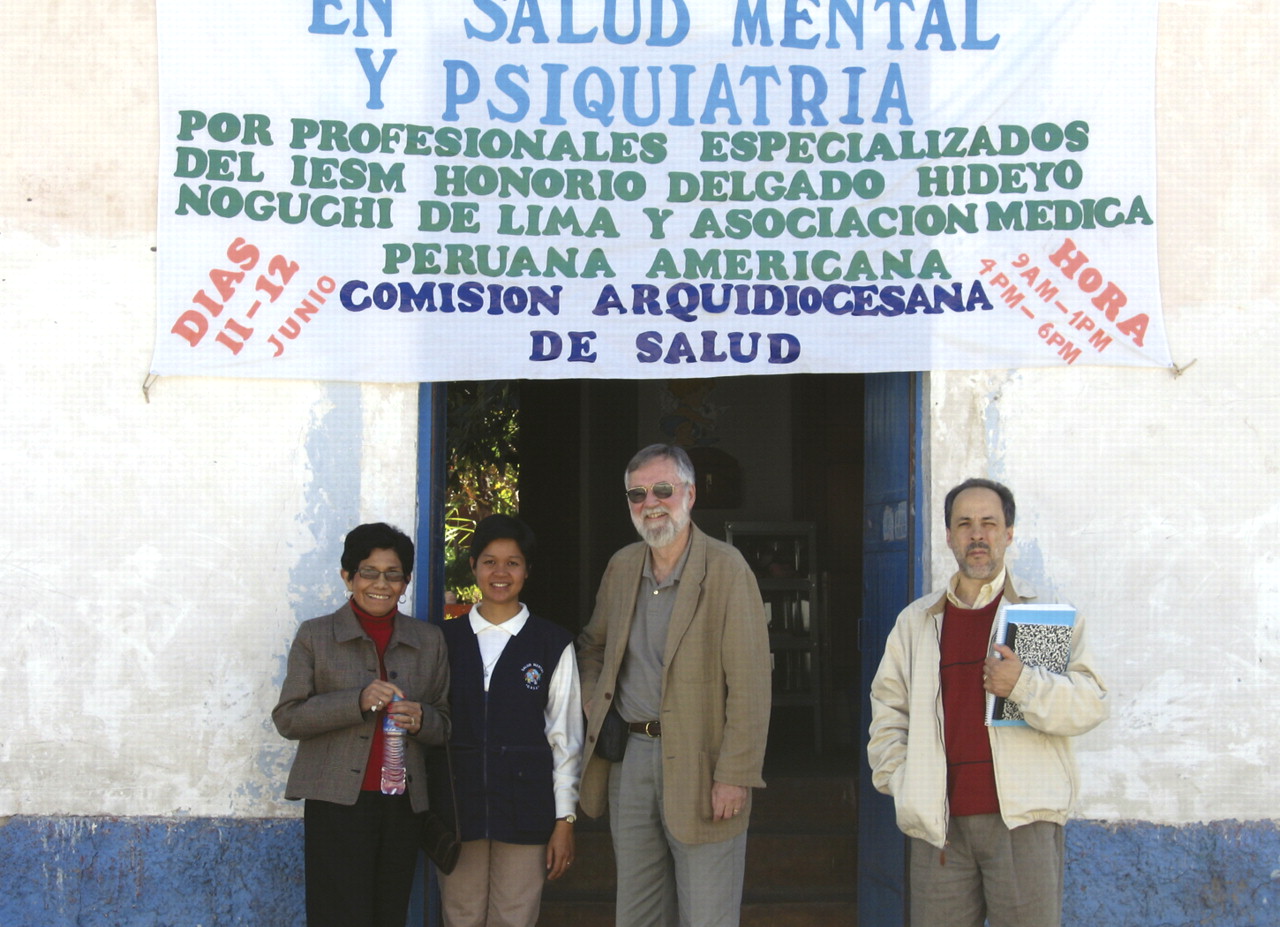

In June 2004, Rego and del Busto flew to Peru with the PAMS mission. They had a list of people to meet in both Lima and Ayacucho, but they really had no idea of how the psychiatric team might make a mental health care contribution in Peru.

“What we really wanted to find out,” said Rego, “is what happens if you get mentally ill in Ayacucho. We spoke with hospital officials, government officials, clergy, anyone we could find, and the answer was, `Nothing.'”

Finally, they went to Carbon's convent. Rego started his inquiries in Spanish, and Carbon replied, “Why don't we speak English—it will make it easier!” And that is when Rego and del Busto learned that she had started a small mental health clinic and decided that together with Phillips they should invest their efforts in her clinic. Formally, the clinic operates under the auspices of the local archdiocese, but there is no religious dimension to the treatment.

Immediately following the Ayacucho visit, the three American psychiatrists began sending monthly donations and psychotropic medications to the clinic. They returned to Ayacucho in November 2004 and June 2005 and plan to visit every six months for the time being. During these visits, they treat patients, train staff, and conduct planning with Carbon. Between visits, they maintain frequent contact with Carbon via telephone and e-mail.

A number of other individuals have been assisting the clinic as well. For example, Matos “is really the heart and soul of the clinic,” said Rego. “He has devoted one weekend a month to the clinic since the beginning, where he works virtually around the clock and is then on call seven days a week by phone from Lima.”

Nurses from Lima help out at the clinic as well. The Peruvian Ministry of Health has started paying for the transportation and room and board for the Peruvian psychiatrists and nurses when they work at the clinic. But they still come on their own time. In addition, the Ayacucho nursing staff provides the daily care at the clinic, some of them on a voluntary basis. Finally, a core of volunteer nonprofessional individuals provides other support.

Various other groups and individuals are helping the clinic too. Carbon's Order of Saint Columban made a sizable financial contribution to get the clinic off the ground. American nongovernmental organizations, including Direct Relief International, have assisted in shipping donated psychotropic medications to Peru. The Milford (Conn.) Rotary Club, in conjunction with Rotary International, is in the process of providing a grant for electronic equipment, and PAMS, under the leadership of Kuon, has supported the clinic. Finally, in addition to their own monthly contributions, the American psychiatrists have conducted fundraising for the clinic.

The clinic was first established on the outskirts of Ayacucho but was moved recently to central Ayacucho. Some 1,500 patients are in treatment. “We have had to stop advertising,” said Rego, “because when we advertise, 60 people will show up for an evaluation.”

“And one of the most important things,” Phillips added,“ is that most of the local clinic staff are being paid reasonable salaries now.”

Medications and Customs

Not surprisingly, getting the clinic up and running has presented various difficulties. For example, Rego said, “Getting medications to the clinic has been a challenge. It is complicated because you are sending very expensive pharmaceuticals, Customs is very complex, and there are a lot of laws regarding health. However, I think we have finally found a solution that works—a Catholic charity in Peru will be the recipient of the donations.”

Still another challenge, he added, is developing a working relationship with a regional hospital in Ayacucho.

There are also certain difficulties facing the clinic staff in its day-to-day operations. For instance, about 60 percent of the people in Ayacucho who visit the clinic speak both Spanish and the local Indian language, Quechua, but people who come from outside the city usually speak only Quechua. The local nursing staff all speak Quechua, but the psychiatrists, including those from Lima, speak only Spanish and thus need the nurses as interpreters for Quechua-speaking patients. Carbon, fluent in Spanish and English, is studying Quechua.

Practicing Pure Psychiatry

Not surprisingly, the American psychiatrists are receiving certain psychological rewards from their clinic efforts and especially from their treatment of patients at the clinic.

“It is gratifying to feel close to people whom you might think are very different from you, but who have very much the same concerns,” Rego commented.

“There is something enormously satisfying about bringing psychiatric treatment to a population that has had none,” Phillips said. “And when we work at the clinic ourselves, it is in a sense doing pure psychiatry. In other words, people come in who are suffering, and you treat them. All these layers of bureaucracy and insurance companies, all the stuff we have to deal with in this country, are just not there. It's just you and the patient.”

“Even getting paid is not there,” Rego chuckled, “which makes it even purer! Patients need and appreciate our help, and it is a wonderful experience.”

Both Rego and Phillips said they are planning on helping the clinic indefinitely. Del Busto followed the June visit to Ayacucho with a visit to a small children's hospital in the Andean town of Puquio. She plans to divide her efforts between Ayacucho and Puqio.

“The long-term clinic plan,” Rego said, “and this may take a very long time, with a 10-year outlook on this, is to build an Andean mental health center that would be a referral center, a treatment center, and a research center.”

“I would say the same,” Phillips added. “Everything in Peru is sort of public psychiatry—the hospitals, the Ministry of Health, and so on. Most of the Peruvian psychiatrists work for the Ministry of Health. The clinic is unusual in that it is separated from all that, although it does receive some financial support from the Ministry hospital in Lima. Our long-term plans at the clinic would surely involve more collaboration with the Ministry.”

More information on the clinic is posted at<www.pamsnational.org/_pdf/ayacucho_mental_health_project.pdf>.▪