The closer individuals are to a disaster, the worse the mental health consequences can be, but time and treatment can reduce symptoms and slow the progression of depression, according to a study of long-term outcomes of victims of the 1988 Armenian earthquake.

Beyond tracking victims' progress, the results of the study can guide allocation of mental health resources following such cat-aclysms.

Just after the earthquake, Armen Goenjian, M.D., and his colleagues organized a mental health team to visit three cities in Armenia. Spitak was close to the epicenter and was almost completely destroyed. One out of every six inhabitants died. Twenty miles away, Gumri lost half its buildings, and about 7 percent of the population died. The capital, Yerevan, 47 miles from the epicenter, suffered little structural damage and no deaths, although constant media coverage meant residents had indirect exposure to the earthquake.

Reconstruction has proceeded slowly throughout the affected areas, so that reminders of destruction remain visible.

The team evaluated 125 adolescents a year and a half after the earthquake, said Goenjian, a professor of psychiatry at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, in an interview. In Gumri, where they set up two clinics, they evaluated and treated 38 youngsters and also evaluated, but did not treat, 58 youngsters. All were students at two schools within walking distance of the clinics. Due to a lack of resources, no intervention was provided at the schools in the other two cities, although team members assessed 63 students in Spitak and 60 in Yerevan. Because of the hardships facing victims and mental health workers in the quake zone, every other untreated student was evaluated at the five-year point (less a few who were lost to follow-up): 32 in Spitak, 27 in Gumri, 30 in Yerevan.

“We used an eclectic approach to treatment that included aspects of cognitive-behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, and psychoeducation,” said Goenjian. “With children, we occasionally used medications to treat nightmares or severe depression.”

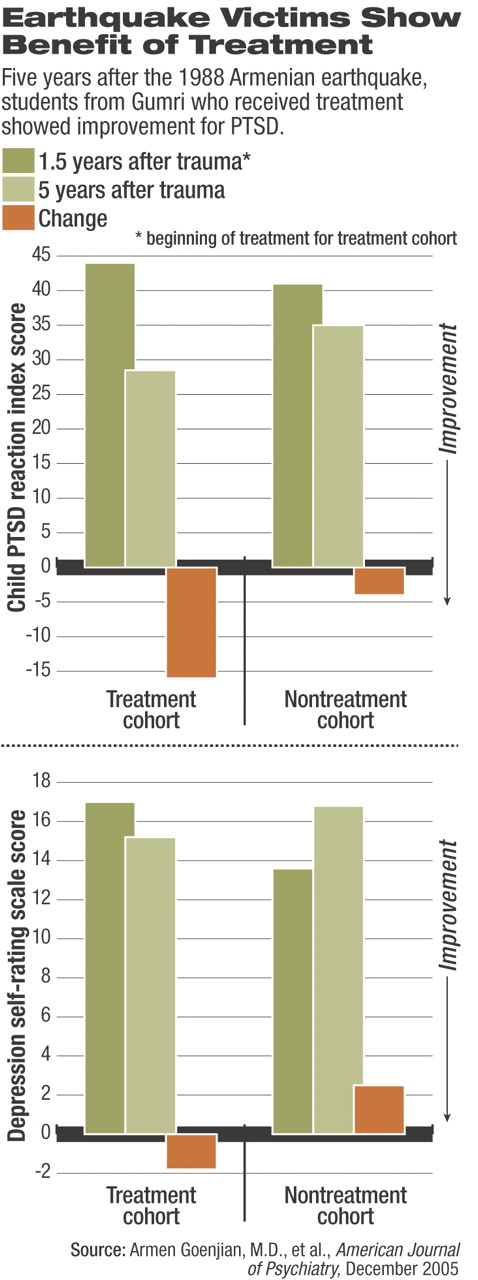

The interventions in Gumri included up to four group sessions over several weeks and an average of two individual sessions held in the school classrooms, he said. Posttraumatic stress symptoms for all subjects were self-reported with the Child Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index (CPTSD-RI). Depression was rated using the 21-item Depression Self-Rating Scale (DSRS).

Eighteen months after the quake, CPTSD-RI scores indicated a dose-dependent pattern, varying inversely with distance from the epicenter. Students in Spitak had the highest scores (53.0), followed by untreated students in Gumri (41.1) and Yerevan (34.7). About 90 percent of those scoring 40 or above met criteria for PTSD, said Geonjian. Five years after the event, scores had dropped significantly but rankings remained in the same order. Only the Spitak scores (47.6) remained above the cutoff point for PTSD (see top chart). Girls scored higher at both time points.

As for depression, scores at 18 months followed the same city pattern, but only those from Spitak surpassed the cutoff score indicating the presence of depression (see bottom chart). The depression scores increased significanlty at the five-year mark only for the untreated Gumri group. Again, girls had higher scores than boys, reaching significance only at the five-year mark.

Among the 36 students in Gumri who received treatment and were available for follow-up, CPTSD-RI scores were significantly lower than those of the 27 untreated students, even though they had been slightly higher at 18 months. Depression scores for treated students were higher at 18 months before treatment began than for untreated students, but the differences nearly evened out at five years as the untreated students showed worsening symptoms and the treated ones improved.

The Armenian experience suggests that the “exposure dose” is a crucial element in public-health planning for disasters, said Goenjian.

“Severity is the key,” he said. “The hypothesis that manmade trauma is worse is not true.”

The effects are additive, said Goenjian. Victims of Hurricane Mitch in Nicaragua who were also caught in a subsequent mud-slide had higher rates of PTSD than those affected by the storm alone. Some Armenian quake survivors had also been affected by prior political unrest, which may have increased their sense of stress.

Psychiatrists and mental health professionals can respond to disasters by using epidemiological tools to assess a cross-section of the affected population and identify probabilities of PTSD, depression, and separation anxiety. The loss of the social and physical infrastructure—homes, friends, family—has an especially strong influence on children, he said.

“Do a meaningful short-term intervention, if needed, focusing on loss and grief reactions, with judicious use of medications,” he suggested.“ Allocate resources for long-term treatment of those who need it.”

Treatment can help supply needed optimism for individual recovery and possibly contribute to reconstructing the community at large, he added.

Am J Psychiatry 2005 162 2302