Most physicians know to screen those who survive a heart attack for symptoms of depression because the psychiatric disorder can contribute to further cardiac trouble. However, new research indicates that younger women may benefit most from such screening, because they are the most vulnerable to depression following a heart attack.

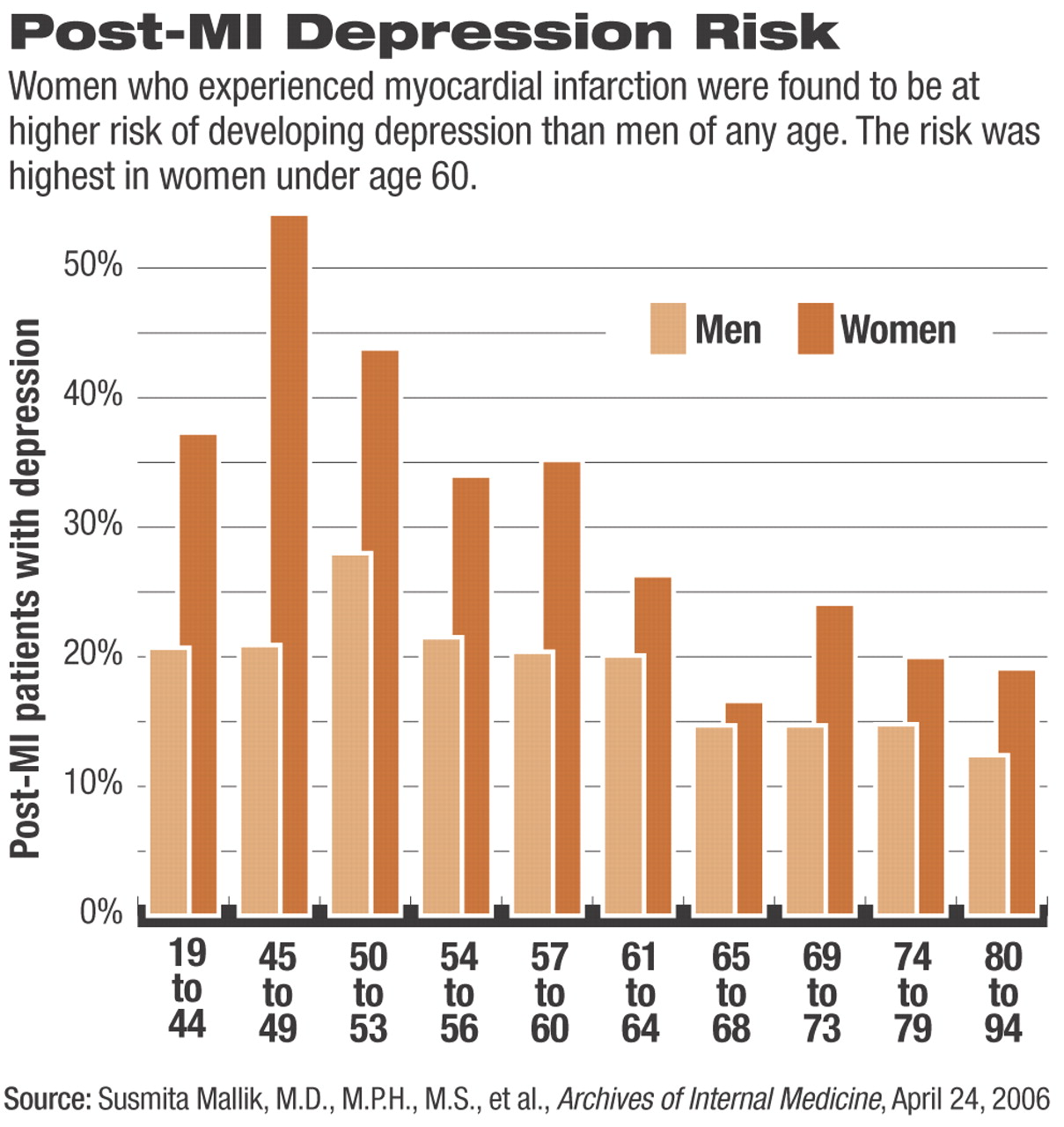

The two-and-a-half-year study of 2,498 survivors of myocardial infarction found that the prevalence of depression is highest in women younger than age 60. The study chose a cut-off point of 60 years because it was the median age in their study population. The highest percentage of patients with depression, however, was found in women aged 45 to 49.

The study, “Depression Symptoms After Acute Myocardial Infarction,” was published in the April Archives of Internal Medicine.

“Clinicians should be aware that women were more likely to show signs of depression after myocardial infarction than were men,” said Susmita Mallik, M.D., lead author of the study and an assistant professor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine. “They should also be aware that depressed heart attack patients are more likely to have worse health status and die [sooner], compared with patients who are not depressed.”

The study stemmed from the finding in previous research that women who had heart attacks had higher mortality rates, and these rates were not based on medical history, clinical severity, or treatments. Earlier studies had discovered that women had depression rates up to twice those of men after heart attacks, but the impact of age was unknown.

The authors were spurred to further drill down among heart attack patients in the light of other research that identified younger women among those most susceptible to depression in the general population.

The findings suggested that screenings for depression should be“ particularly aggressive” among younger women hospitalized for heart attacks, Mallik said. Depression during hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction confers three to five times higher adjusted odds of death within six months, according to previous research.

Mallick's study assessed subjects for depression during hospitalization for myocardial infarction and classified them as depressed if they scored at least 10 on the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders Brief Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ). The study found that younger people had higher mean PHQ scores than older patients (6.4 vs. 5.0), and younger women had the highest PHQ scores (8.2).

Forty percent of women who had suffered a heart attack at age 60 or younger had depression, Mallick found, and 21 percent of women older than 60 had depression. In contrast, only 22 percent of men aged 60 or younger had depression. Women 60 or younger were three times more likely to have depression after a heart attack than were men over 60.

Only about 27 percent of depressed patients in the study had a history of depression prior to the heart attack.

The study does not formally recommend any treatment for such patients because trials of depression treatments after heart attack have not identified clear advantages for a particular approach. Randomized future trials are needed, Mallik said, to show whether treating depression improves health outcomes after a heart attack.

“At the same time, depression is an important illness in its own right, and it is important to treat it regardless of other conditions,” Mallik said.

The reasons for the higher rates of depression among younger women who have had heart attacks remain unclear. The researchers hypothesized that younger women are more predisposed to stressors, such as poverty, low education levels, responsibilities at home and work, and taking care of both children and aging parents.

Others theorize that estrogen cyclicity and metabolic syndrome may be a factor in predisposing younger women to depression, but the researchers stressed that they do not know for certain.

Mallik also was recently awarded an American Heart Association grant to follow up on the study's findings. She plans to use the grant to compare the effects of depression on prognosis after heart attack between women and men. Mallik hypothesizes that depression is a stronger predictor of adverse outcomes in women following heart attacks and may explain the higher risk of adverse outcomes in women.