Only 1 of 5 of troops returning from Iraq or Afghanistan and found at risk for developing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was referred for further mental health evaluations, according to a report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO).

In response, Department of Defense (DoD) medical officials said they will make criteria for referral more explicit but said that the report understates the number of soldiers who had access to care.

The report was mandated by Congress as part of the National Defense Reauthorization Act of 2005.

“This is about screening, not treatment,” said Cynthia Bascetta, M.A., M.P.H., director of health care for the GAO. “We're not even at the stage of knowing whether they were treated.”

The report analyzed information culled from the standard forms filled out by members of the armed services as they returned from the two theaters of war. These Post Deployment Health Assessment (PDHA) forms ask about physical and psychosocial health. They include four questions intended to determine risk for PTSD. Three or four positive responses to these questions indicate a higher risk of developing the disorder. After completing the forms, service members discuss their responses with a health care professional, who may be a physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant.

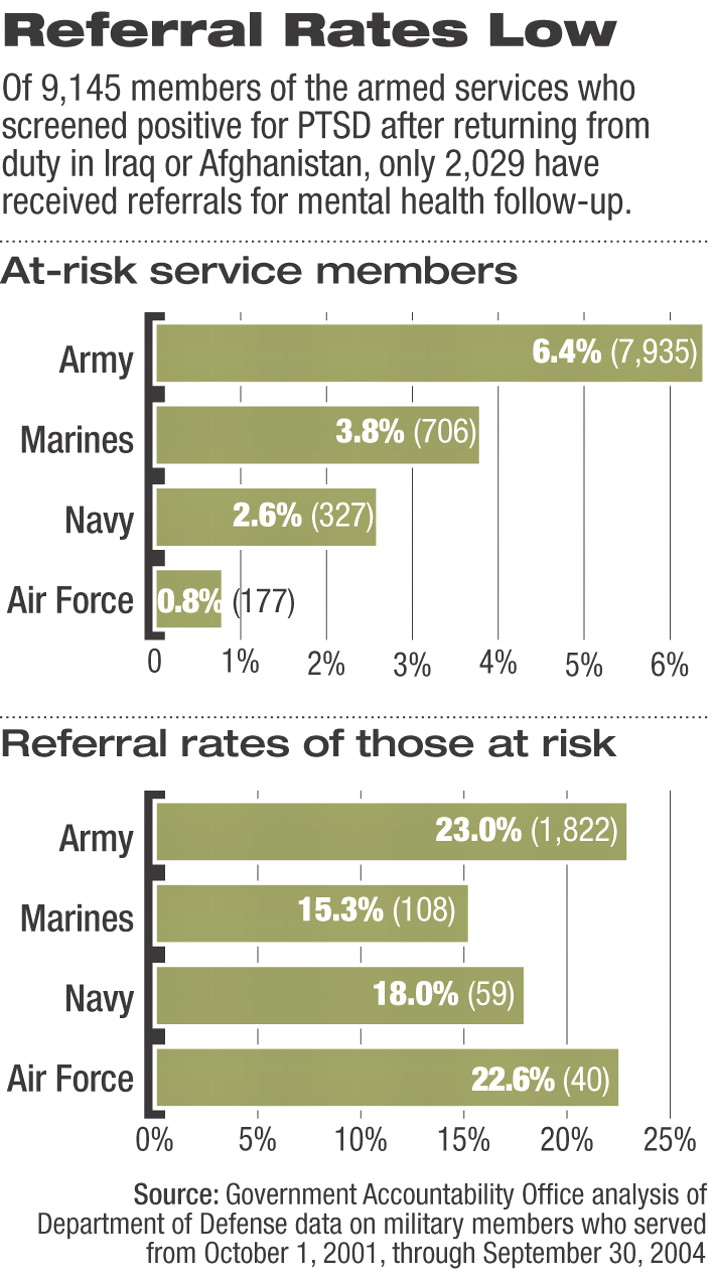

The GAO examined computerized data on 178,664 troops and found that 9,145 (5 percent) were at risk for PTSD, but only 2,029 (22 percent) had been referred to mental health specialists.

“[The Department of Defense] cannot provide reasonable assurance that [Iraq and Afghanistan] service members who need referrals receive them,” concluded the report, which was issued in May. “DoD did not identify the factors its providers used in determining which... service members needed referrals.”

“This is about screening, not treatment. We're not even at the stage of knowing whether they were treated.”

Referral depends on the clinical judgment of the health care providers who review the forms, and variations among service branches in the frequency of referrals may represent inconsistent patterns in that judgment, said the report. The Army referred 23 percent of those answering three or more questions positively, while the Marines referred 15 percent, the Navy 18 percent, and the Air Force 23 percent.

Pentagon medical officials suggested that the GAO report presented an incomplete picture of the screening and referral process.

The doctors, nurses, or physician assistants who review the PDHA forms with the service members go over any questions checked “yes” and inquire about specifics, said Air Force Col. Bob Ireland, M.A., D.Min., M.D., program director for mental health policy. The clinicians review the person's medical history and ask about recent experiences, symptom severity, current presence of symptoms, family relationships, and other details.

“Maybe they don't meet PTSD diagnostic criteria, but their condition may still impact their lives,” said Ireland.

“Medical assessments are done to enhance access to care,” said Michael Kilpatrick, M.D., deputy director of force health protection and readiness at the DoD, in an interview. “In the military system, most referrals are to primary care doctors, who can then refer to mental health providers as needed. But we don't have the data to know if someone was seen in primary care because of a referral or for another reason.”

The GAO looked at processes, not clinical evaluations of patients, said Ireland. The assessment on return from a war zone was designed to provide access to care for individuals, not serve as an epidemiological tool, he said.“ It's not unusual for someone in a doctor's office to be screened, but it's inappropriate to take those questions out of the doctor's office to apply them in a wider context.”

“Are people getting care?” asked Kilpatrick. “There is not a problem with access. We need to look at outcomes, especially as troops deploy for a second or third time.”

In a written statement responding to the GAO, the DoD agreed to identify factors used by clinicians in deciding who gets referred, but also said it did not agree with the report's conclusions that “reasonable assurance” was unavailable to say troops were not getting needed referrals. Referral decisions required an understanding of both clinical concerns and “occupationally unique” demands of military work.

The Pentagon expressed concern about too quickly medicalizing and pathologizing normal combat stress reactions, asserted the potential risks of false positives, and noted that the PDHA was not the only route to care for returning troops. The statement also pointed out the need to consider conditions other than PTSD, like depression.

“[I]ssues relating to diagnosis and treatment are not germane to the referral issues we reviewed and were beyond the scope of our work,” wrote the GAO in its rebuttal to the DoD. “Instead, our work focused on the referral of service members who may be at risk for PTSD because they answered three or four of the four PTSD screening questions positively, not whether they should be diagnosed and treated.”

“The Pentagon has agreed with our conclusions and has agreed to make changes by October,” added Bascetta. The department must send a letter to the GAO giving details of how it will implement the report's recommendations.

The GAO report is posted at<www.gao.gov/new.items/d06397.pdf>.▪