Specific positive personality traits in adolescence can protect people against some adversity in early adulthood, a new longitudinal study suggests.

The investigation was headed by Elizabeth Bromley, M.D., a VA/UCLA Robert Wood Johnson clinical scholar. Results are in press with Comprehensive Psychiatry and became available online in April.

“There is little doubt that personality strengths are understudied in psychiatry,” Andrew Skodol, M.D., director of the Department of Personality Studies at New York State Psychiatric Institute, told Psychiatric News. “[So] this unique, prospective, community-based study is important. It shows that personality strengths play a considerable role in identifying adolescents who will be resilient in the face of stressful life events.”

And as John Oldham, M.D., chair of psychiatry at the Medical University of South Carolina and a personality disorder authority, said, “Unlike most studies of personality disorders, this [one] focuses on resilience... [and the results shine] a bright light on ways to shape prevention efforts, particularly to help youth in stress-burdened families or environments.”

Bromley and her coworkers enrolled 688 teens (average age 16) in their study. The teens were representative of those in the northeastern United States regarding several demographic factors.

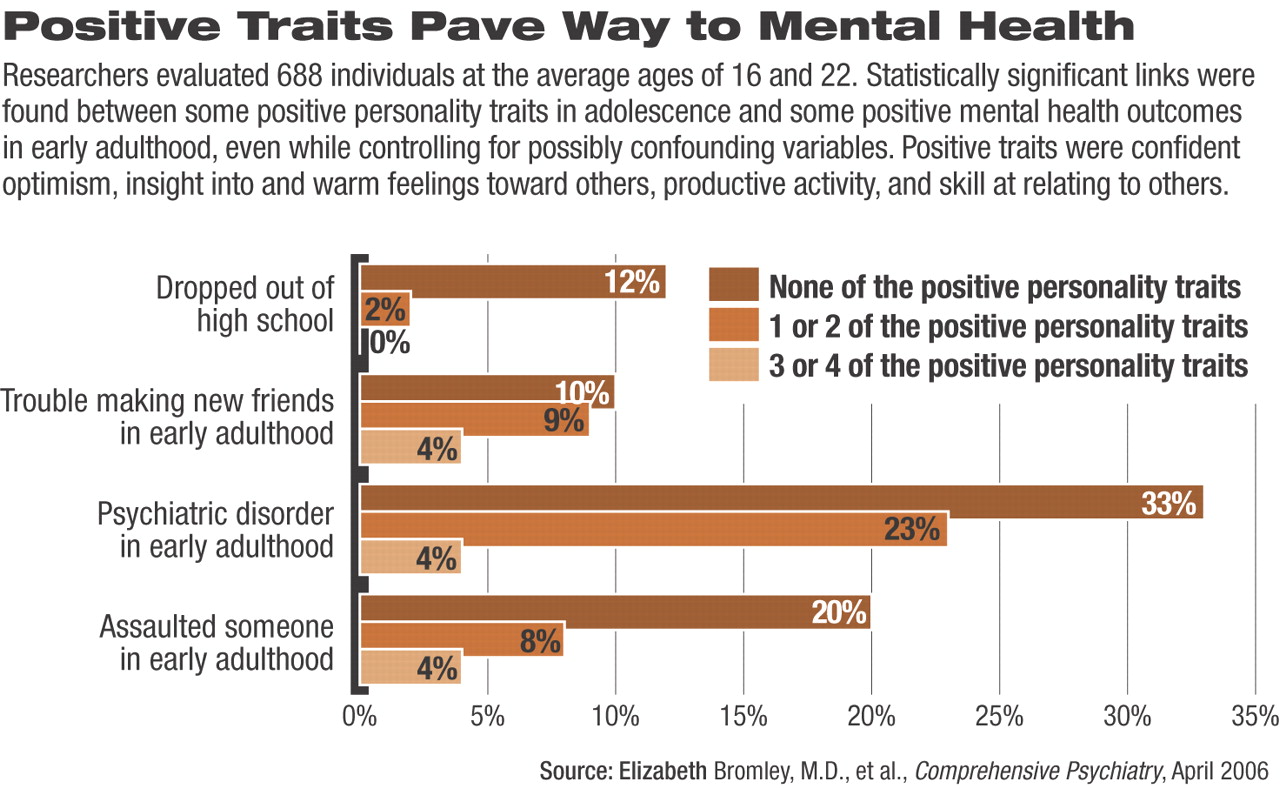

Subjects were evaluated for four personality traits known to contribute to health, life satisfaction, and positive interpersonal relationships: confident optimism, insight into others and warm feelings toward others, productive activity, and skill at relating to others.

Subjects also reported stressful life events that they had experienced during the previous two years, such as death of a loved one, parental divorce, serious illness, or a romance rejection.

Bromley and her colleagues then followed the subjects until they were young adults (average age 22) and assessed them for four negative outcomes: interpersonal difficulties, educational or occupational problems, psychiatric disorders or suicide attempts, and violent or criminal behaviors.

Finally, the investigators looked for connections between subjects' possession of the four positive personality traits in adolescence and their later susceptibility to these negative mental health outcomes.

They found a statistically significant dose-response relationship between the number of positive personality traits and a decreasing likelihood of each of the four negative mental health outcomes in early adulthood, even after possibly confounding factors were taken into consideration (see chart on facing page).

Moreover, subjects who experienced numerous stressful events as adolescents and who had fewer of the traits were found to be at elevated risk of deleterious mental outcomes as young adults, whereas subjects who experienced numerous stressful events as adolescents yet had more of the traits did not share this vulnerability.

This finding suggests that one way such traits safeguard adult mental health is by mitigating the pernicious impact of childhood adversity. A retrospective study reported last year suggested the same conclusion (Psychiatric News, September 2, 2005).

In addition, specific positive personality traits in adolescence could be linked with specific positive mental health outcomes in early adulthood, even after possibly confounding variables were taken into consideration.

For example, subjects who had had the highest level of confident optimism in adolescence were significantly less likely than the others to be anxious. Subjects with the highest level of insight into others and warmth for others in adolescence were significantly less likely than those without this trait to abuse substances. Subjects with the highest level of productive activity in adolescence were significantly less likely to be depressed in early adulthood. And the subjects who were the most skilled at relating to others in adolescence were significantly less likely to engage in physical fights resulting in injuries.

The findings have practical implications for youth.

For example, as Bromley and her group pointed out in their report, confident optimism was the only trait “that predicted reduced risk for anxiety disorders, suggesting that promoting the development of confidence and optimism during adolescence may help prevent the onset or recurrence of anxiety disorders during adolescence and early adulthood.”

And even if confident optimism and insight and emotional warmth are“ hardwired temperament,” Oldham asserted, surely the other two personality traits—productive activity and skill at relating to others—can be learned.

The results also have implications for psychiatrists.

For instance, Bromley told Psychiatric News, “Assessing an adolescent's personality resources, even in a quick way. .ought to provide clinicians with useful prognostic information. Attending to an adolescent's strengths provides the clinician with a more complete portrait than can be concluded from an assessment of personality difficulties and psychiatric symptoms alone....[And] since attending to an individual's assets is a respectful and generous approach, we wonder if clinicians could use the assessment of resiliency to strengthen the therapeutic alliance.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Greater Los Angeles VA Healthcare System, and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

An abstract of “Personality Strengths in Adolescence and Decreased Risk of Developing Mental Health Problems in Early Adulthood” can be accessed at<www.sciencedirect.com> by clicking on “Browse A-Z of journals,” then “C,” then “Comprehensive Psychiatry.” ▪