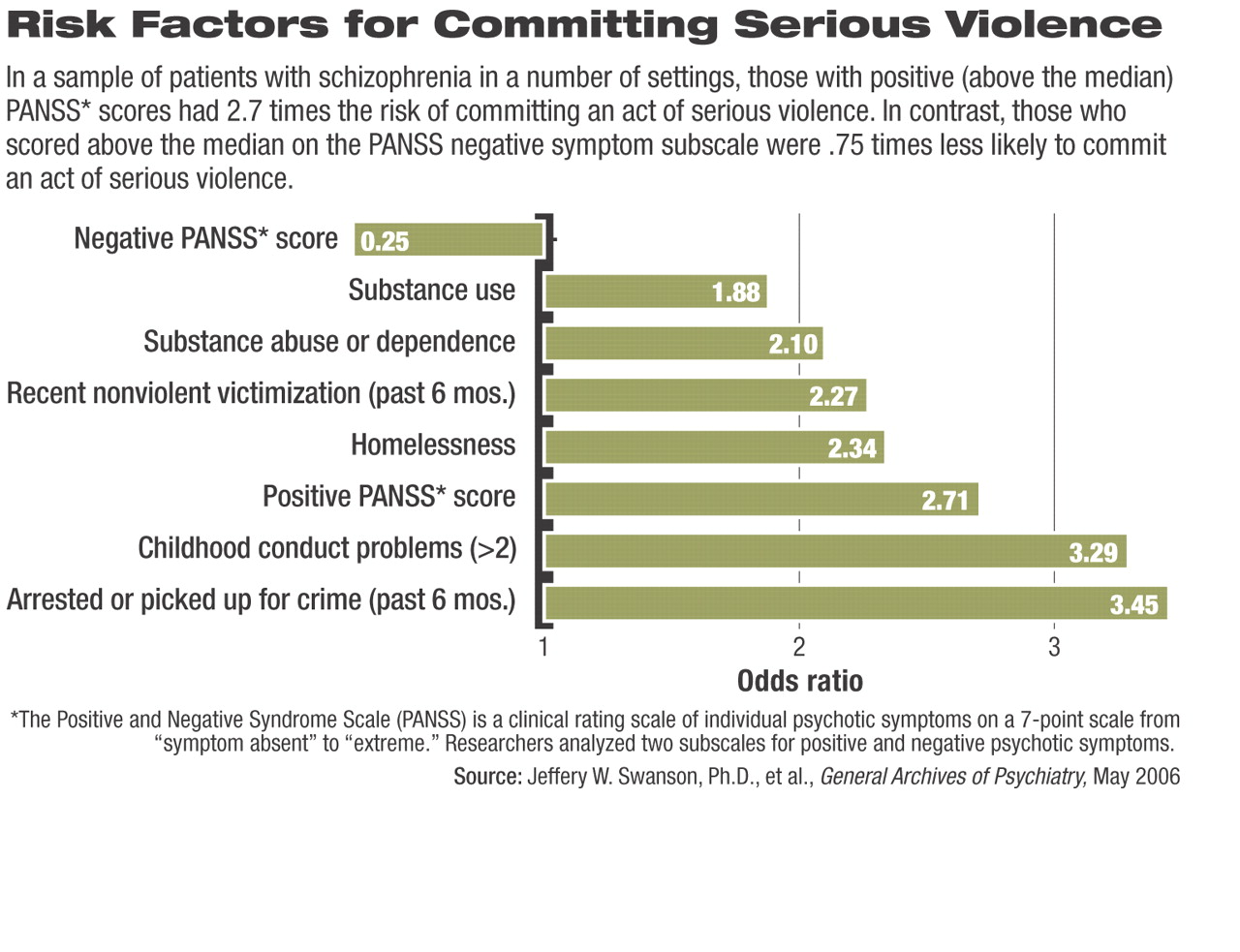

Though violent behavior is the exception rather than the rule among people with schizophrenia, one large study found that positive psychotic symptoms such as persecutory ideation and grandiosity were associated with an increased risk of serious violence.

In contrast, negative symptoms such as passivity and social withdrawal were associated with a decreased risk of violent behavior.

“I think these findings reinforce the view that violence risk reduction should be an important goal and component of community-based treatment for schizophrenia and that risk reduction needs to focus on clinical as well as nonclinical factors that may contribute to violence,” one of the study's investigators, Marvin Swartz, M.D., told Psychiatric News. Swartz is a professor and head of the Division of Social and Community Psychiatry at Duke University Medical Center.

Nonclinical factors related to violence in the sample included residing in restrictive housing (such as a halfway house, psychiatric hospital, or jail) or with family, not feeling “listened to” by family members, and a recent history of police contact.

Data came from baseline interviews of 1,410 people with schizophrenia enrolled in the National Institute of Mental Health Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study.

The CATIE study was a randomized trial conducted between January 2001 and December 2004 at 56 clinical sites in 24 states to investigate treatment effectiveness and outcomes among patients with schizophrenia.

Each study site screened inpatients and outpatients for study eligibility. Those who were deemed to be appropriate for participation had adequate decision-making capacity and were receiving suboptimal treatment with antipsychotic medications due to problems with efficacy or tolerability.

During a baseline assessment and before the patients were randomized to experimental treatments for the CATIE study, lead investigator Jeffrey Swanson, Ph.D., and colleagues assessed the patients for violent behavior in the prior six months. He is an associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Duke.

To assess the generalizability of the sample, Swanson compared participants with a “quasi-random” sample of 1,413 patients enrolled in the Schizophrenia Care and Assessment Program, an observational study of schizophrenia treatment in the United States.

Though the CATIE sample had a lower proportion of minority patients, the two samples were similar in other demographic characteristics, age, and a variety of clinical characteristics.

The similarities provide “some confidence that the CATIE project's randomized, controlled-trial design did not result in a biased selection of more severely ill and impaired patients,” the authors noted.

They used the MacArthur Community violence Interview to measure minor and serious violence. Researchers defined minor violence as a simple assault without injury or weapon use (shoving or slapping another person, for example) and serious violence as assault using a lethal weapon or resulting in injury, threat with a lethal weapon, or sexual assault.

Researchers gathered information on violent acts by the subjects through patient self-reports and family collateral information (when available).

Researchers also assessed patients at baseline for factors such as available social support, severity of illness, and awareness of mental health problems, among others. They also used the Structured Clinical Interview for Axes I and II of DSM-IV Disorders–Patient Edition to confirm schizophrenia diagnoses and assess childhood conduct problems.

In addition, they used the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) to rate severity of psychotic symptoms.

Among the 1,410 patients, the six-month prevalence of any violence was 19.1 percent: 219 patients (15.5 percent) reported minor violence, while 51 (3.6 percent) reported serious violence.

Both Clinical, Nonclinical Factors Play Role

Swanson found that serious violence was associated with several clinical and nonclinical factors.

For instance, those who scored above the median on the PANSS for positive psychosis symptoms had 2.71 times the risk for serious violence as those with lower scores.

Patients who scored above the median for negative psychotic symptoms had about a quarter of the risk as those who scored below this point.

People with suspiciousness and persecutory delusions also had an increased risk of engaging in serious violence (odds ratio 1.46, p<.001), as did those who responded to hallucinations (odds ratio 1.43, p<.001).

Also, serious violence was significantly associated with grandiosity (odds ratio 1.31, p=<.001) and excitatory symptoms (odds ratio 1.30, p=.02).

In addition, the findings showed that 27.5 percent of those who committed serious violence were arrested, and 16.1 percent of those with minor violence were arrested for some crime in the previous six months. Arrest data were gathered by self-report.

Swanson told Psychiatric News that he thought that positive psychotic symptoms may lead to violence in several ways: “A person with a severe thought disturbance may hear voices directing him or her to attack someone else,” he said. With persecutory delusions, “a person may act on a false perception of threat of harm from someone” in which case“ a violent act might seem like self-defense from the distorted perspective of the person with psychosis.”

Younger age, childhood conduct disorder problems, and a history of arrests were nonclinical factors associated with serious violence, the researchers found.

Nonclinical factors associated with minor violence included limited or no vocational activity, residing in “restrictive” housing with family, and not feeling “listened to” by family members.

“Studies show that when violent behavior occurs, it tends to involve family members and acquaintances much more often than strangers,” Swanson noted. “People with severe mental illness may also experience emotional conflict within family relationships. .that can contribute to the risk of violence.”

He speculated that a “cause-and-effect connection” might play a role in the link between minor violence and lack of a job. “Being unemployed and having no meaningful work to do—especially over a long period of time—can be stressful and may indirectly increase risk of assaultive behavior in people with schizophrenia.”

Majority Do Not Act Violently

Swanson emphasized that the majority of patients with schizophrenia have positive psychotic symptoms but do not engage in violent behavior.

He acknowledged that “serious violence [among people with schizophrenia] may be unlikely, but it's a bad thing when it happens” and that clinicians and advocates for patients' rights may have different interpretations of the study findings.

“Psychiatrists worry about patient violence not because it's especially common, but in part because of clinicians' legal liability for adverse, but rare, outcomes of their treatment decisions.”

In contrast, patients' rights advocates, who often oppose involuntary treatment, may be concerned because national surveys have shown that the“ majority of the public believes (erroneously) that mentally ill people are generally dangerous,” and this belief could be used to justify legal strategies for overriding people's right to refuse mental health treatment, Swanson said.

He noted that homicides or other serious violent acts committed by a person with schizophrenia usually become “banner headlines” in newspapers“ even if other potential factors are involved” in the violent act.“ you will not read a companion story about the thousands of other people with mental illness in the same city who never did anything violent.”

The findings, he continued, “reinforce the view that violence risk-reduction should be an important goal of community-based treatment for schizophrenia” and that “risk reduction needs to focus on clinical and nonclinical factors that may contribute to violence.”

Further research in this area, he said, should focus on studying violence in people with mental illness from a developmental perspective, “taking into account the complex interactions between social environment, features of psychiatric illness, and personal characteristics of individuals as they change over time.”

The study was funded by the Foundation of Hope, an organization in Raleigh, N.C., that promotes research into causes and treatments of mental illness.