The cost of buprenorphine treatment and the 30-patient limit on physicians who offer the in-office opioid addiction treatment were identified as the leading barriers to broader physician use of this intervention, a recent study found.

The study was required by the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000, the legislation that legalized the office-based treatment for addiction to heroin and opioid painkillers.

The findings also undercut concerns that led to the inclusion of the law's requirement that physicians can provide buprenorphine treatment to no more than 30 patients at a time. Despite concerns by federal drug officials, little evidence has emerged that the only available office-based treatment for opioid addiction has spurred further illegal drug use.

In 2005 the law was amended to eliminate the 30-patient limit on group practices and entire clinics.

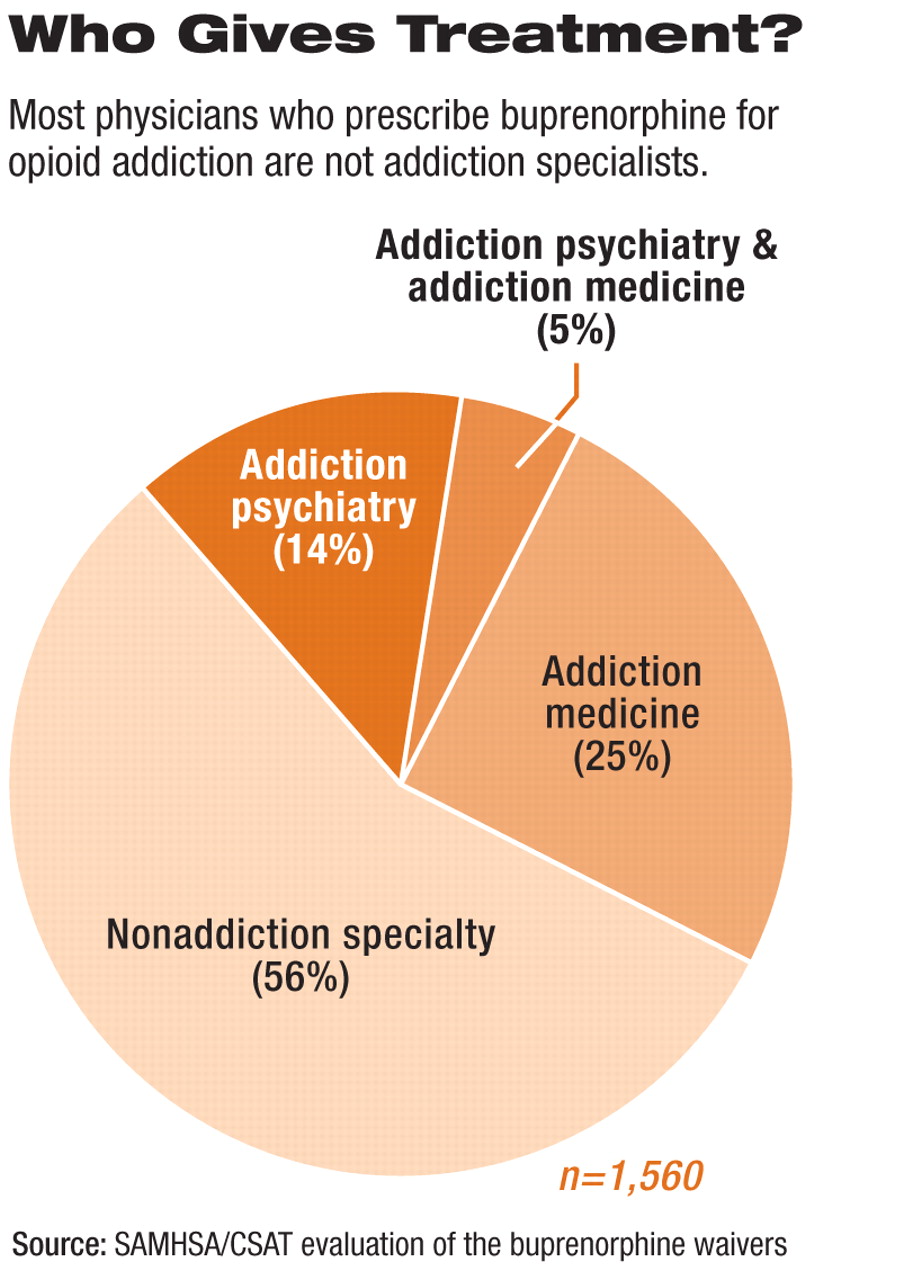

The study reported on the results of surveys conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's (SAMHSA) Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. About 1,800 physicians who have received waivers to prescribe the drug were interviewed, as were nearly 400 drug abusers under treatment with buprenorphine. The data represented responses received through May.

The surveys found consistently high treatment continuation or treatment completion rates among all treatment groups, and 74 percent of prescribing physicians reported the drug was effective by one month into treatment.

The study found evidence that the 30-patient limit has, however, had a major impact. More than 25 percent of physicians reported that the limit led to reduced prescribing of buprenorphine.

“This study confirms our hopes about the effectiveness of buprenorphine and also helps to illuminate the things that need to be done to help more patients reach this powerful medicine.”

A separate postmarketing survey required by the Food and Drug Administration and conducted by researchers at Wayne State University similarly found that in the first quarter of 2006, among surveyed physicians who prescribe buprenorphine, 29 percent had turned away at least one patient because of the limit. On average, physicians turned away 9.3 patients, with a total of 2,009 patients turned away by the survey respondents.

“I was surprised how high this number was, and it speaks to the need to raise the limit and increase the number of physicians who provide this service,” said Charles Schuster, Ph.D., the postmarketing study author and director of the Clinical Research Division on Substance Abuse at Wayne State University. Schuster made his remarks during a Senate symposium on buprenorphine in August.

The postmarketing study, which included surveys of physicians and drug abusers and Internet searches to gauge the level of abuse of the drug, found little illegal diversion. The three-year study found buprenorphine treatment is clinically effective and well accepted by patients and has increased the availability of medication-assisted treatment well beyond the estimated 240,000 methadone treatment slots available.

Although federal drug-enforcement officials expressed fears that buprenorphine would work its way onto the illicit drug market, the postmarketing study was unable to identify a single case of a drug-addicted patient who began his or her drug “career” with buprenorphine.

Herbert Kleber, M.D., director of the Division on Substance Abuse at the New york State Psychiatric Institute and a former deputy director in the Office of National Drug Control Policy, said at the Senate forum that office-based buprenorphine treatment has brought into treatment many patients who were reluctant to seek care when the only option was frequent attendance at a methadone clinic. The treatment of an estimated 200,000 patients by more than 7,800 physicians authorized to prescribe buprenorphine has not had the negative outcomes feared by some drug enforcement officials.

Kleber and others at the symposium said that blame for the lack of access to treatment for the estimated 1 million heroin addicts and 4.4 million nonmedical users of prescription opioid analgesics also lies with insurance programs that do not adequately cover buprenorphine's cost or the costs to the prescribing physician who provides this intervention. Many unemployed people and low-income working people, for example, lack access to medical care, and many addicts are unaware that the medication is an option available to them.

The SAMHSA surveys found that nearly half of the prescribing physicians surveyed reported that the cost of the drug was among the top challenges to prescribing buprenorphine.

Another limit repeatedly cited by physicians at the symposium was the reluctance of many physicians to deal with “both the stigma attached to addicts and the extensive oversight exercised by federal and state law enforcement agencies,” Kleber said.

Congressional supporters of buprenorphine treatment promised they would push for removal of the 30-patient limit on physicians authorized to prescribe the drug.

“We need to remove this limit and frankly, I don't know how anyone could oppose that at this point,” said Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), in an interview with Psychiatric News. He said he plans to push for removal of the limit before the end of the current session of Congress as a crime-control measure. The measure is included in legislation to reauthorize the Office of National Drug Control Policy (S 2560), which the full Senate is slated to consider in September. There is no House bill aimed at removing the 30-patient limit.

Sen. Carl Levin (D-Mich.), who described the buprenorphine treatment option as a “landmark” in addiction treatment, said more effort is needed to expand the treatment's use beyond the less than 2 percent of primary care physicians authorized to use it. He noted that only 2,910 general practitioners out of 242,924 have been certified to prescribe the drug. The evidence of the treatment's benefits and lack of adverse impact, Levin said, show the need to remove legislative limits that have resulted in long waiting lists and lack of access for many addicts.

“This [SAMHSA] study confirms our hopes about the effectiveness of buprenorphine and also helps to illuminate the things that need to be done to help more patients reach this powerful medicine,” Levin said.

Supporters of buprenorphine treatment hope to increase physician participation by expanding the required eight-hour training sessions to include an online alternative. Elinore McCanceKatz, M.D., Ph.D., president-elect of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry, said her organization—like APA— developed a Web-based course that leads to waiver eligibility. The alternative will make it easier and less costly for physicians to receive training in office-based opioid addiction care.

“Going forward, we plan to continue to try to train as many physicians as possible to provide these services to patients,” she said.

Further information on buprenorphine treatment is posted at<http://buprenorphine.samhsa.gov>. APA's online buprenorphine course is posted at<www.psych.org/edu/bup_training.cfm>.▪