For Rhode Island psychiatrist Brandon Krupp, M.D., it's as simple as this—psychiatric hospitals aren't jails, and psychiatrists aren't jailers.

That's what he told state authorities when he resigned from his position as chief of psychiatry at Eleanor Slater Hospital in Cranston, R.I., after Gov. Donald I. Carcieri sought continued hospitalization of a convicted sexual predator who had completed a 17-year prison sentence.

Krupp's resignation and his declaration—psychiatrists aren't jailers, hospitals aren't jails—have received widespread support. Even Carcieri, in a public statement about the case, seemed to acknowledge that hospitalization was not the ideal solution for what to do with people no one wants in their community.

“Unfortunately, this situation demonstrates that we must strengthen Rhode Island's criminal laws so we can better protect our children from this type of vicious predator,” Carcieri said. “As a beginning, I have already promised to introduce a version of Jessica's Law, which requires a minimum mandatory 25-year prison sentence, followed by lifetime electronic monitoring, for convicted child molesters.”

(Jessica's Law is named after a 9-year-old Florida girl who was raped and murdered last year.)

As Psychiatric News went to press, 40-year-old Todd McElroy was still in Eleanor Slater Hospital awaiting a hearing to determine whether he belongs there. McElroy, who had been convicted of raping a minor, has schizophrenia and had been moved from prison in 2004 to the forensic unit of the hospital for specialized inpatient treatment not available in the prison. He was treated successfully, according to Krupp.

“There was a point when he needed hospital-level care,” Krupp told Psychiatric News. “We provided that care, and he got better. Some 15 months later he was stable enough that we petitioned Superior Court to have him returned to corrections.”

At that point, according to Krupp, corrections officials did not object. But the proceedings took so long that in the ensuing period McElroy completed his prison sentence and was due to be released.

It was only then, Krupp said, that two physicians from the corrections department petitioned to have McElroy hospitalized.

Petition Called Politically Motivated

Krupp believes it was politically motivated. “The governor wanted him off the streets,” he told Psychiatric News. “I am as concerned as anyone about sex offenders being in the community unsupervised, because I have treated their victims. But it makes no sense to misuse the medical system for political ends.”

A spokesperson for the governor's office told Psychiatric News that Krupp's allegation that the state is using the hospital as a prison is“ completely false” and pointed to the fact that two physicians from the department of corrections have indicated in their petition that McElroy needs hospitalization.

But Paul Lieberman, M.D., president of the Rhode Island Psychiatric Society, observed that a formal hearing to determine whether that's indeed the case has yet to happen, and that the forensic specialist at Eleanor Slater Hospital, as well as Krupp, had determined that McElroy did not need hospitalization.

“Our concern is that there was no clear assessment that this patient needed to be in the hospital,” Lieberman said. “We support Dr. Krupp without speaking to the merits of whether this man needed to be in the hospital. The appropriate procedures should have been followed instead of turning to the hospital as a de facto solution.”

The special circumstances complicating the case in Rhode Island—McElroy's schizophrenia and the question of whether his pedophilia was secondary to untreated psychosis—appear to be nuances in a larger national drama about the role of psychiatric hospitalization of criminals who have finished prison sentences, but who are still regarded by the public as potentially violent threats to the community.

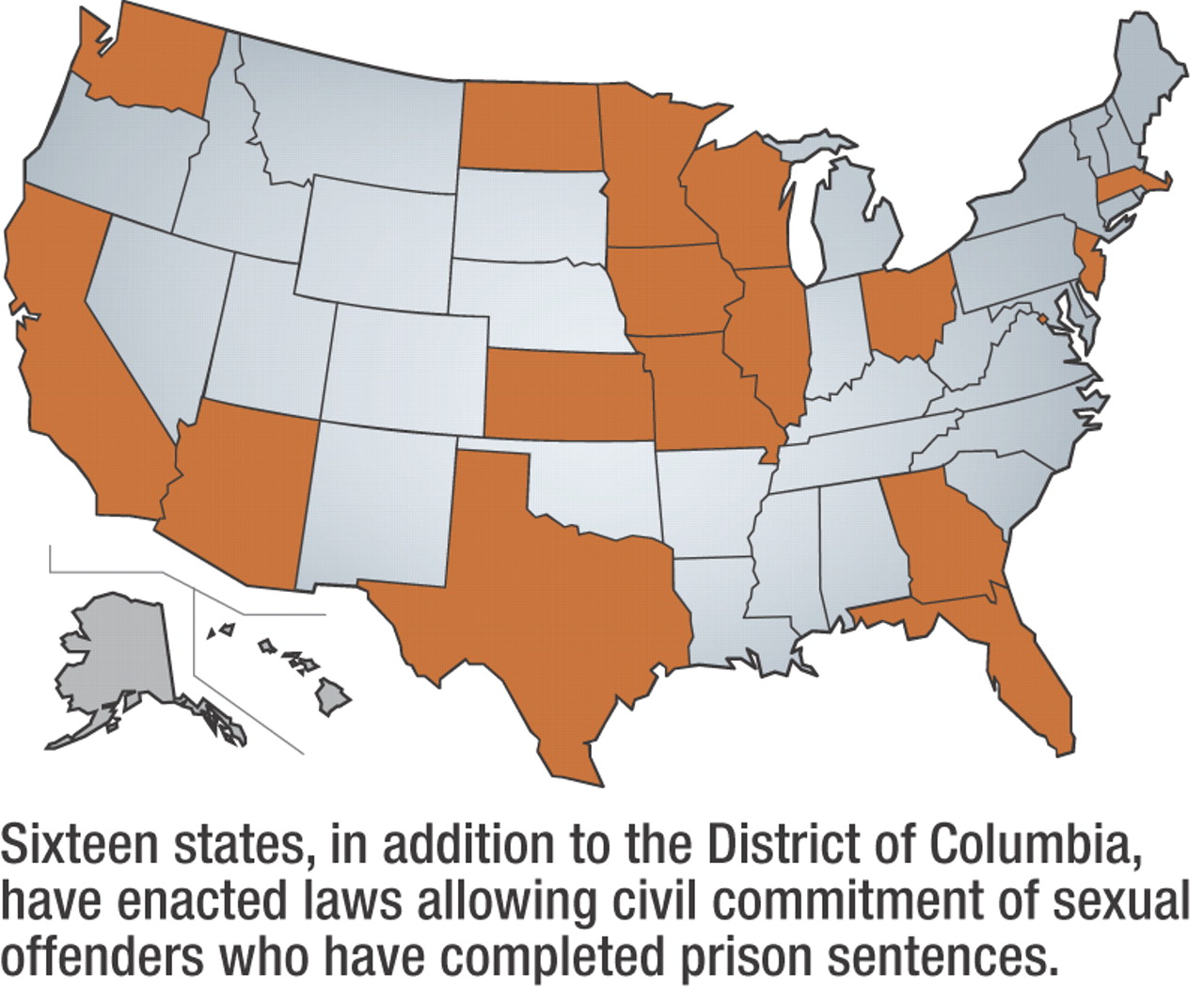

Sixteen other states and the District of Columbia have laws that allow the state to detain sexual offenders in psychiatric hospitals after they have completed their prison terms. Those laws were upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1997 in Kansas v. Hendricks.

Last year New York Gov. George Pataki (R) issued an executive order to state corrections and mental health officials to begin assessing and detaining some convicted sexual offenders after Pataki failed to get legislation approved allowing the commitment of violent sexual offenders to state mental hospitals at the end of their prison terms (Psychiatric News, November 18, 2005).

Nonetheless, state efforts to keep potentially violent sexual predators out of the community have conflicted with traditional conceptions of the appropriate role of psychiatric hospitalization—and of physicians in making determinations about who belongs in a hospital.

“The current generation of sexual predator acts, in trying to solve a difficult and intractable problem, goes about it in the wrong ways,” said Michael Perlin, J.D., a professor of law at New York University Law School and director of the International Mental Disability Law Reform Project in New York. “We are taking people who do not appear to have serious mental disorders and treating them as psychiatric patients. It's bad for them, and it's bad for the providers of treatment.”

Though APA does not have an official statement on the Rhode Island case, in 1999 the APA Task Force on Sexually Dangerous Offenders opposed state laws allowing commitment of sexual offenders, stating in its report that the diagnosis of sexual predator in such laws is based on “a vague and circular determination that an offender has a `mental abnormality' that has led to repeat criminal behavior.”

The statement continues, “Thus, these statutes have the effect of defining mental illness in terms of criminal behavior. This is a misuse of psychiatry, because legislators have used psychiatric commitment to effect nonmedical societal ends.”

Inteferes With Physician Judgment

Howard Zonana, M.D., chair of the task force, noted that psychiatry has never defined what disorders qualify for regular civil commitment, a breadth of latitude that most psychiatrists have been comfortable with until now.

“There may be certain severely mentally ill offenders who qualify for civil commitment at the end of their sentences,” he said. “It's when other people start trying to decide who should be in a psychiatric hospital that physicians get upset, especially when they use personality diagnoses or traits that are indistinguishable from typical convicted felons.”

In Vermont Gov. Jim Douglas (D) has urged passage of the Omnibus Public Safety Bill to establish a civil commitment process for the treatment of all violent offenders—not only sexually violent offenders—who have completed prison terms.

The bill is opposed by a coalition of groups that include the Vermont Psychiatric Association (VPA), American Civil Liberties Union of Vermont, Vermont Human Rights Commission, Vermont Association of Mental Health, and Vermont Protection and Advocacy, among others.

“The VPA has expressed its strong opposition to the development of a `civil commitment' program in Vermont,” said child psychiatrist David Fassler, M.D., who is the legislative and public affairs representative for the VPA and a trustee-at-large of APA.

“We believe it's a misuse of the mental health statutes and a diversion of limited treatment resources,” Fassler told Psychiatric News. “We've expressed this view through the local media and in testimony before legislative committees. We've also joined a statewide coalition of advocacy groups organized to oppose the proposal. We intend to monitor this issue closely and to play an active role in the ongoing public dialogue on this topic.”

Jonathan Weker, M.D., who is the VPA representative to the coalition opposing the bill, said that the discussion in Vermont, like those in Rhode Island and New York, has been driven by publicity about heinous crimes committed by offenders released from prison.

“The whole debate is discussed in terms of public safety,” he said. “It's almost a sham, any notion of truly providing treatment. Even if one were to say that some of these people [in prison] do have mental illnesses with some clinical validity, that's given very short shrift. One review of the legislation revealed that people committed under the law would get six hours of treatment a week.

“It's disingenuous to say that only the day after someone has finished a criminal sentence is that person able and ready for treatment,” Weker said. “If anyone on the law enforcement side really thought mental health treatment for sexual offenders was meaningful, why not start treatment early on during an inmate's incarceration?”

Weker echoed others in saying that if society wants people detained longer for violent crimes, the solution is longer sentences, not hospitalization.

“We don't mean to overlook the public safety issue,” he added.“ That's real, and it worries us as citizens as much as anyone else. The problem is with sentencing. I don't think you can cure bad sentencing with civil commitment.”

Meanwhile, Krupp appears to have no regrets about leaving his post at Eleanor Slater Hospital. He sees patients in his private practice specializing in geriatric neuropsychiatry and the assessment and treatment of impaired physicians and other professionals.

“I felt like I could no longer do my job if medicine could so easily be trumped by politics,” he said. “It's important to understand that [violent offenders] pose a danger to society, but pretending a hospital is a prison doesn't keep anyone safe.” ▪