The first of many analyses to come from the National Institute of Mental Health's (NIMH) Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) provides much-needed, long-term data on the potential for recovery from manic and depressive episodes and predictors of relapse into subsequent mood episodes.

“In spite of really optimized treatment with guideline-based pharmacotherapy, combined with psychoeducation provided by clinicians specifically trained in the management of bipolar disorder, nearly half of our patients suffered a recurrence within two years,” said Roy Perlis, M.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and one of several STEP-BD investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. Perlis and his co-investigators published their report in the February American Journal of Psychiatry.

“I think [these data] indicate the severity [of bipolar disorder] overall, and while we have some wonderful, newer treatments and some very effective older treatments,” Perlis told Psychiatric News,“ we still have a lot of work to do.”

STEP-BD is the largest national research program aimed at determining the best treatment practices for bipolar disorder. Begun in 1998 and concluded in September 2005, researchers treated 4,360 patients with bipolar disorder (I, II, or NOS) who were followed long term to determine the most effective treatment or combination of treatments to combat depressive and manic episodes and to prevent relapse.

“We also found that one of the strongest predictors of recurrence in our sample was the presence of residual mood symptoms following recovery,” Perlis said. “Even when patients were largely well, if they continued to be somewhat symptomatic, they were more likely to have a relapse. In short, those residual symptoms matter.”

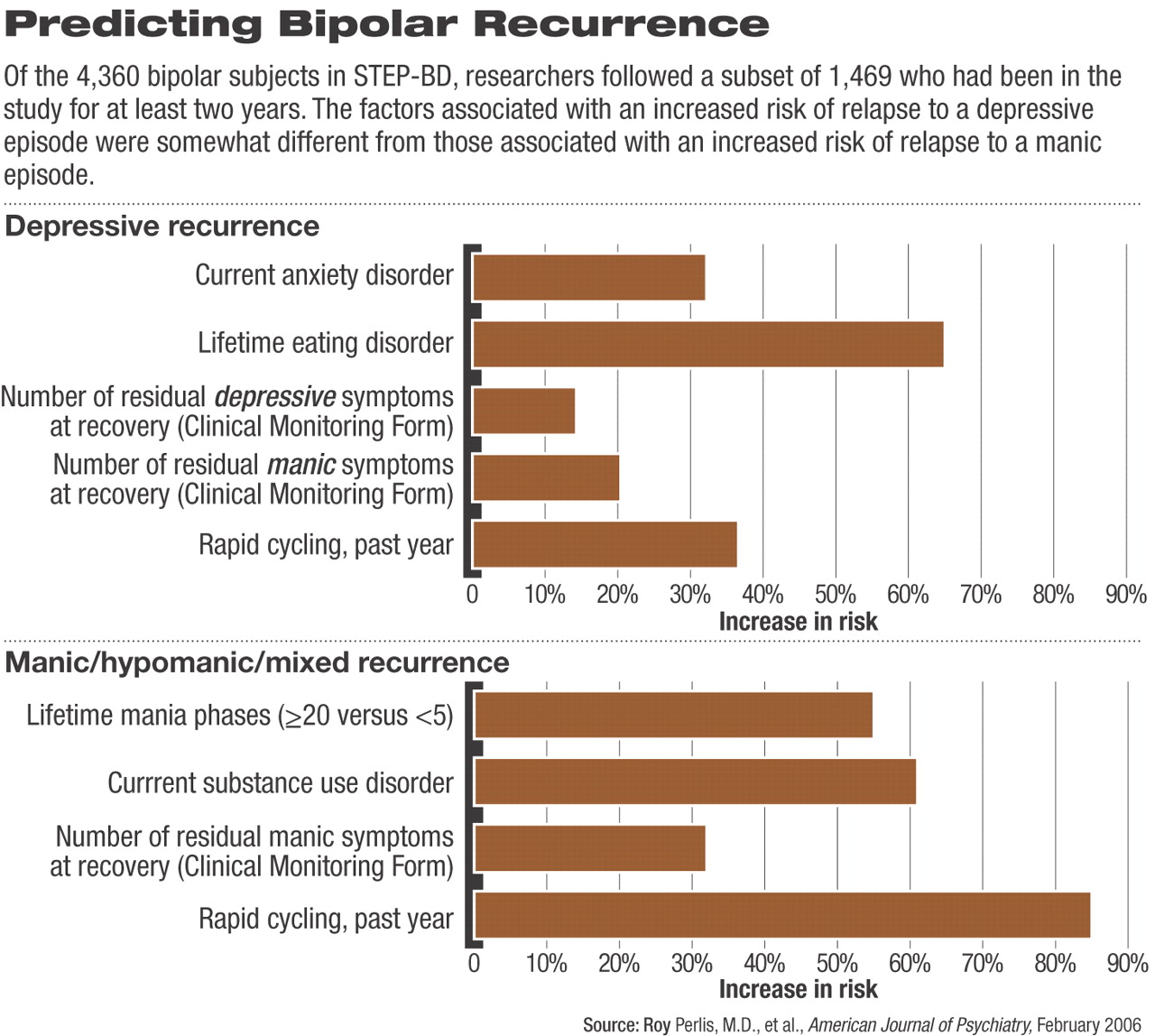

For the predictors of recurrence analysis, Perlis and his team looked at a subset of the full patient sample, focusing on 1,469 patients who had at least two years of participation in the STEP-BD program. The researchers found that slightly more than half (858 patients, or 58 percent) of this group achieved recovery, defined as having no more than two symptoms of the disorder for a period of at least eight weeks during the two-year follow-up period.

Within that two-year window, nearly half of those who achieved recovery (416 patients, or 48.5 percent) relapsed; almost twice as many patients who relapsed suffered a depressive episode (298 patients, or 34.7 percent) than those relapsing to a manic, hypomanic, or mixed episode (118 patients, or 13.8 percent).

Perlis and his co-authors concluded in their article that “taken together, these results demonstrate that mood episodes in bipolar disorder, and particularly depressive episodes, are prevalent and likely to recur in spite of guideline-based treatments.”

Patients in STEP-BD, they noted, “received evidence-based care from specialized clinicians with training in the use of standardized assessments, combination pharmacotherapy, and psychosocial treatments where appropriate. In addition, participants received at minimum a core psychosocial educational intervention.”

As such, the co-authors wrote, “the finding that nearly half of the study participants nonetheless suffered at least one recurrence during follow-up highlights the need for development of new interventions [for] bipolar disorder.”

“I think [the importance of residual symptoms] parallels the major depression literature, where we've come to see that full remission is really the goal of treatment,” Perlis told Psychiatric News.“ Improvement is great, but remission is really critical. I think [these results] suggest that we need to take the same kind of focus in bipolar disorder—which many clinicians already do—and that is to treat to remission, not simply recovery. It emphasizes the importance of those residual symptoms and their association with risk of recurrence.”

Interestingly, somewhat different factors appeared to be associated with relapse to a depressive episode versus relapse to a manic/hypomanic/mixed episode (see chart). For example, a current substance use disorder increased the risk of manic relapse, but not depressive relapse, while a current anxiety diagnosis was associated with increased risk of a depressive relapse but not manic relapse.

The STEP-BD protocols were intended to represent an effectiveness study, and patients in the STEP-BD's Standard Care Pathway could receive any intervention believed to be clinically indicated by their clinician. In addition to rigorous guidelines for monitoring the progress of individual patients, clinicians adhered to pharmacotherapy guidelines based on published treatment guidelines (APA's revised Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder, the Expert Consensus Guideline Series: Medication Treatment of Bipolar Disorder, and the Department of Veterans Affairs' Clinical Practice Guidelines for Bipolar Disorder).

STEP-BD also incorporated a “core psychosocial intervention.” All patients received a workbook and videotape describing the intervention, which emphasized alliance-building and provided techniques for recognizing and managing stress, negative thought patterns, problems in interpersonal interactions, and sleep disturbances.

Perlis expressed some level of discomfort with the STEP-BD protocols being described as “state of the art.”

“We didn't do anything that can't be done by any physician in the community,” Perlis explained, “and that was an important principle [in designing the study]—we wanted this to very specifically be generalizable across the country.” Perlis also emphasized that“ there will be much more to come from STEP-BD that will focus more on specific treatment questions. There are several studies embedded within the larger STEP-BD design looking more closely at psychosocial interventions and providing a head-to-head comparison of different pharmacotherapies.”

Am J Psychiatry 2005 163 217