Prenatal stress in humans has been found to cause premature birth, low birth weight, and problems with cognition and behavior.

One means by which prenatal stress unleashes these conditions may be by thwarting the production, after birth, of nerves in the hippocampus region of the brain. The reasons are because prenatal stress has been found to decrease hippocampal nerve growth in both juvenile monkeys and adult rats and because such nerve growth is thought to be involved in both cognition and emotions.

Thus, a crucial question is, Could the noxious effects provoked by prenatal stress on hippocampal nerve growth after birth be reversed? Djoher Nora Abrous, Ph.D., director of INSERM research at the Francois Magendie Institute in Bordeaux Cedex, France, and her colleagues conducted an animal study to find out and got an affirmative answer, as they reported in an article in press with Biological Psychiatry.

They mated 43 female rats. Half were stressed each day from day 25 until delivery. Stress consisted of restraining the pregnant females in cylinders for 45 minutes, three times a day. The other half served as controls and were left undisturbed throughout gestation.

After birth, half of the litters obtained from stressed mothers and half from control mothers were raised by their mothers and left undisturbed until weaning. The other half of the litters from the stressed mothers and control mothers were also raised by their mothers until weaning, but were exposed to an enriched environment as well. It consisted of 15 minutes of handling by researchers daily.

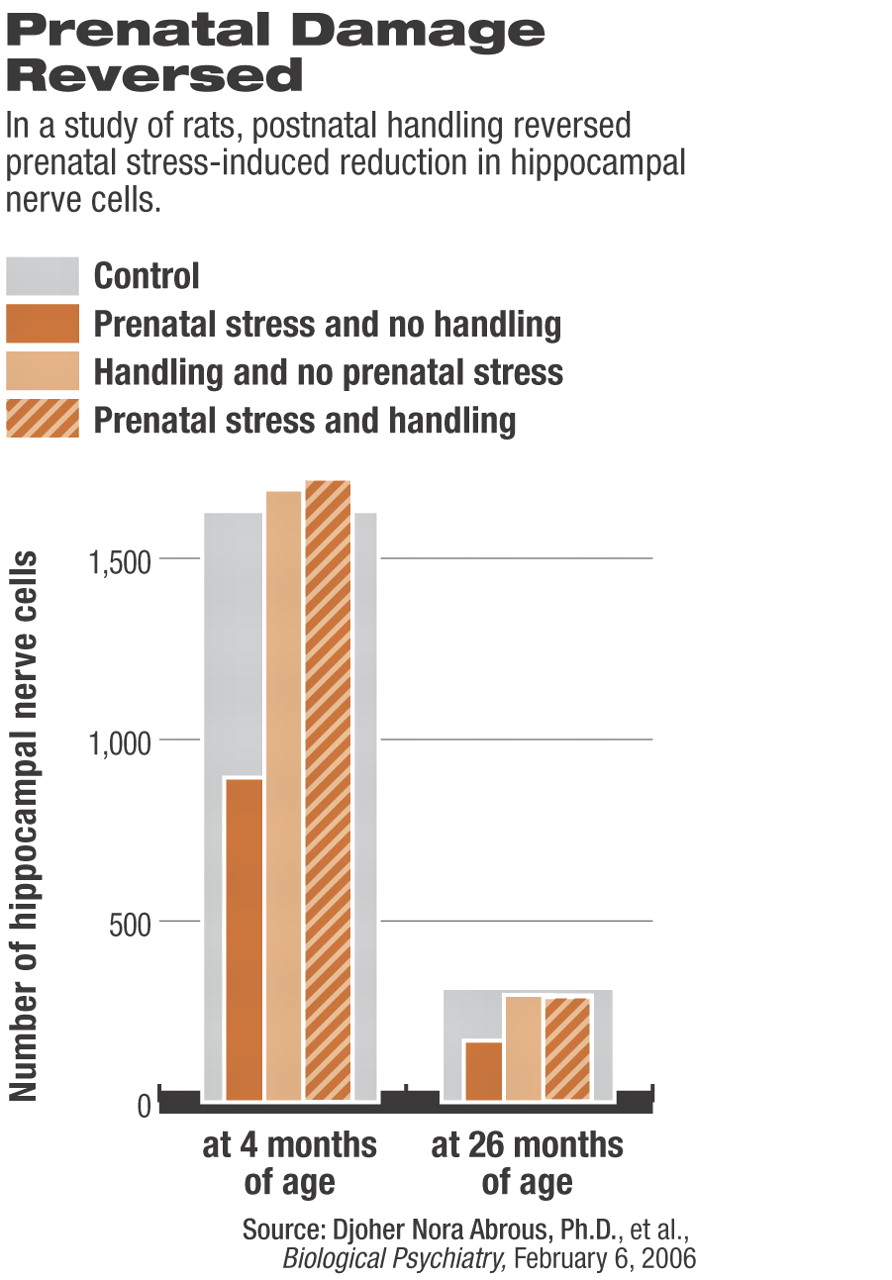

Then, after weaning, between 18 and 20 pups were selected from each of the four groups for follow-up. The scientists then followed the four groups of rat pups to determine whether prenatal stress had had an impact on hippocampal nerve growth and, if so, whether an enriched environment (infant handling) could neutralize the impact.

When the pups were 4 months old, the researchers found, hippocampal nerve growth was similar for all groups except the one that had been prenatally stressed but not handled. It had significantly less hippocampal nerve growth than the other three groups had. Even more striking, results from when the pups were 26 months of age suggested that such a reversal was maintained over the entire lifespan.

The question now, of course, is whether the findings apply to humans.

“This study opens the door to the idea of being able to undo biological changes that occur during fetal development through proper intervention,” Judy McKay, M.D., told Psychiatric News.“ This is an exciting concept [and] has important clinical implications for the possibility of developing appropriate interventions and treatments to prevent some of the long-term effects of maternal gestational stress.”

McKay, a Columbia, S.C., psychiatrist, is also a member of APA's Corresponding Committee on Infancy and Early Childhood.

“This study appears to show that the negative effects of stress during gestation of rats can be reversed,” Lois Flaherty, M.D., a Boston psychiatrist and chair of APA's Council on Children, Adolescents, and Their Families, commented. “The study needs to be replicated, but if it turns out that it can be repeated with the same results in other laboratories, it would have some important implications for how we might reverse the negative effects of psychosocial adversity in humans.”

The study was funded by INSERM (Institut National de la Sante et de la Recherche Medicale) at the University of Bordeaux.

An abstract of “Postnatal Stimulation of the Pups Counteracts Prenatal Stress-Induced Deficits in Hippocampal Neurogenesis” is posted at<www.journals.elsevierhealth.com/periodicals/bps/article/PIIS006322305014009/abstract>.▪