A new study has come to the same conclusion as two earlier reports: a common diabetes medication, metformin (Glucophage), appears to be effective at blocking the sometimes significant weight gain associated with second-generation antipsychotic medications (SGAs). What was new in the latest report was the age of the patients in the study: children and adolescents aged 10 to 17.

The report by David klein, M.D., Ph.D., an associate professor of medicine and pediatric endocrinology at the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, and colleagues appeared in the December 2006 American Journal of Psychiatry. Their work was supported in part by an investigator-initiated award from Eli Lilly and Co.

Eli Lilly markets the SGA olanzapine (Zyprexa) and has ties to other companies that market antidiabetic drugs. The Glucophage brand of metformin is marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb, which also markets the SGA aripiprazole (Abilify). Two coauthors of the report hold patents relating to the use of metformin to counteract weight gain with psychotropic medications.

Klein and his colleagues conducted a protocol known as an “add-on, parallel-design trial” in which they enrolled 39 patients aged 10 to 17 who had been taking one of three SGAs—olanzapine, quetiapine (Seroquel), or risperidone (Risperdal)—for up to one year and had gained more than 10 percent of their pretreatment body weight while on the SGA. No diagnostic criteria were reported to indicate why these child and adolescent patients were taking an SGA.

Metformin is an antihyperglycemic agent that improves glucose tolerance in patients with type 2 diabetes. It decreases hepatic glucose production, decreases intestinal absorption of glucose, and improves insulin sensitivity by increasing peripheral glucose uptake and utilization.

At the beginning of the study, each of the 39 patients was randomly assigned to having either metformin or a matched placebo added to their SGA regimen for 16 weeks. In addition, all patients and their participating families received the same three sessions of generic dietary counseling. At baseline, and at weeks 4, 8, 12, and 16, several measures were examined including height, weight, waist circumference, a series of laboratory tests, and screening for adverse events.

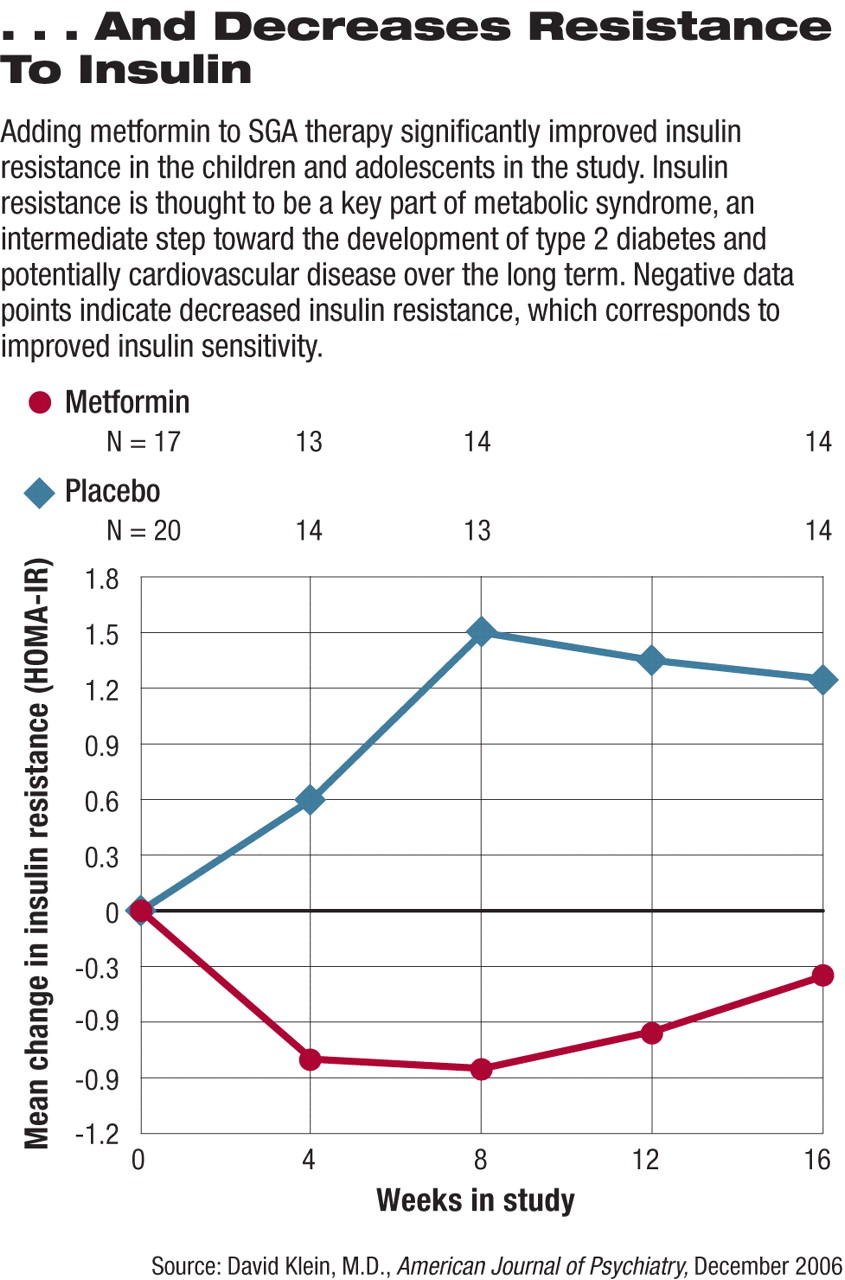

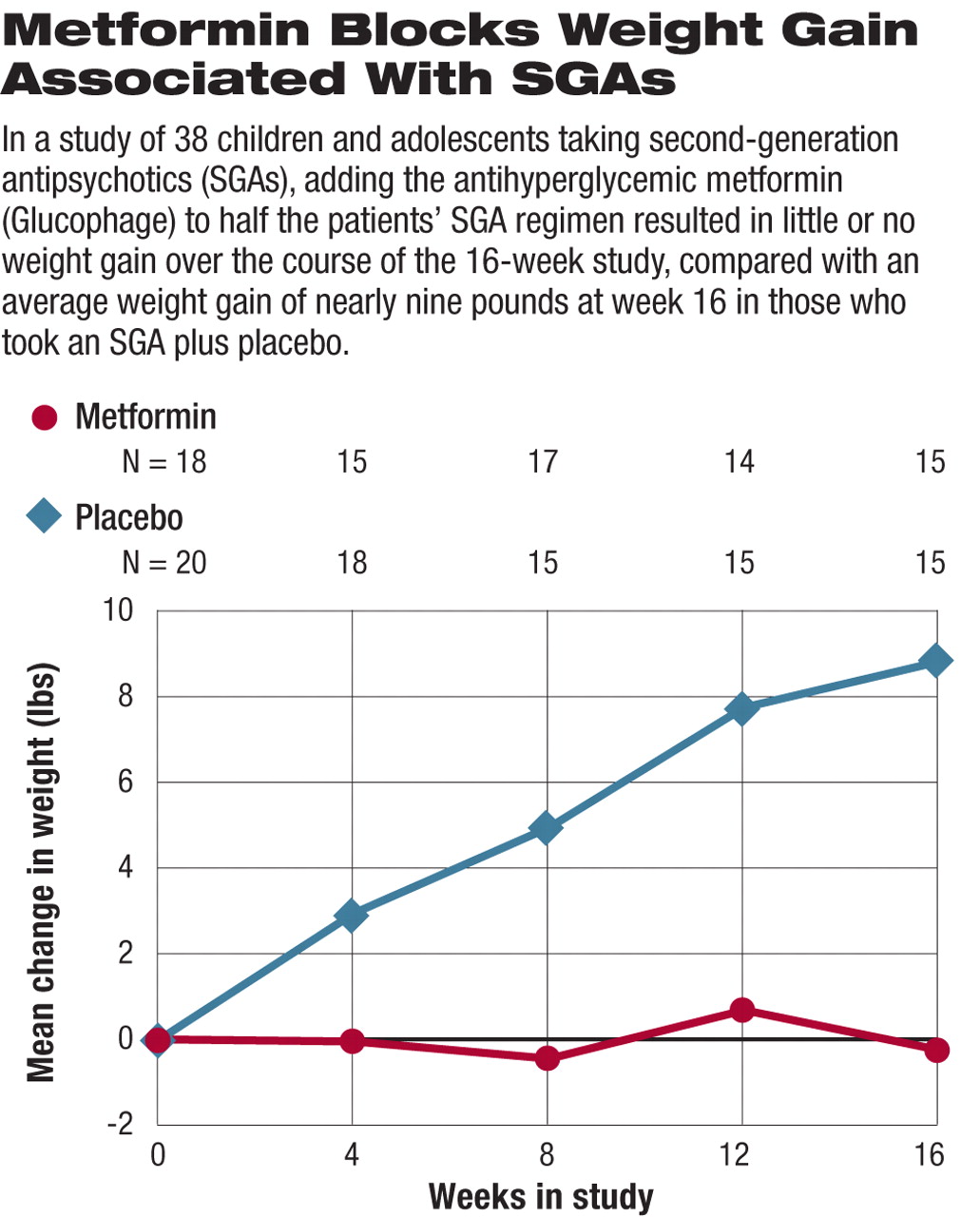

At study completion those who were randomly assigned to placebo had gained an average of 8.8 pounds and had an average increase in body mass index (BMI) of 2.4 pounds/m2 (see graph top right). Those who took metformin along with their SGA, on average, lost 0.26 pounds and had an average decline of 0.9 pounds/m2 in their BMI. In addition, measures of insulin resistance—a potential precursor to diabetes—increased significantly in those on placebo while remaining stable in those taking metformin (see graph below right).

Since it is rare that a medication trial reports such an indisputable result, those with expertise in the field took note.

“I'm not at all surprised that you could take children, or adults for that matter, with the kind of metabolic profiles that these subjects appeared to have and see significant beneficial effects with a medication like metformin,” said John Newcomer, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis. Newcomer chairs the APA Council on Research's Workgroup on Antipsychotics and Metabolic Risk. “I think the real issue is, Where does metformin fit into treatment considerations for people taking antipsychotic medications, and especially, where does it fit for children?”

In an editorial accompanying the report, Kenneth Towbin, M.D., chief of clinical child and adolescent psychiatry in the Intramural Research Program at the National Institute of Mental Health, described the report as“ extremely timely,” noting that the “prescription rate of atypical antipsychotics in children is following a familiar cycle—initial gradual use followed by accelerating, widespread practice. Awareness of cardiovascular and metabolic risks has yet to cool clinicians' enthusiasm.”

“The results are notable,” Towbin said, “for the clear differences between treatment groups in average weight gain, absolute BMI... [and] there were impressive changes in measures of insulin resistance.”

While Towbin called the report “a welcome investigation addressing a serious problem,” and stated that the “findings are good news,” he qualified his comments by noting that “any zeal should be tempered.” The study does not address the long-term safety of metformin, for example, or whether the weight loss is sustained.

“What concerned me about this paper, and the commentary, is that there wasn't as much discussion as I would have hoped for, as far as removing the offending agent prior to... adding a second drug to treat the adverse effects,” added Newcomer. There was no discussion of re-evaluating the antipsychotic therapy and perhaps switching patients to a medication associated with less weight gain liability, he noted.

P. Murali Doraiswamy, M.D., an associate professor of psychiatry and chief of the Division of Biological Psychiatry at Duke University School of Medicine, told Psychiatric News, “This is a terrific pilot study and a much needed one.”

Yet Doraiswamy, who is an expert on the association between SGAs and metabolic adverse effects, added, “Before we debate whether or not to add metformin to minimize metabolic side effects, our first priority should be large clinical trials to prove the [SGAs] are effective in children. Otherwise, we will be putting the cart before the horse.”