When Princeton University Press published Nancy Andreasen's new work on 17th-century poet John Donne in 1967, it should have been a pinnacle for the young author.

Still in her 20s, she had been a Woodrow Wilson Fellow at Harvard and a Fulbright Fellow at Oxford, had completed her doctorate in English literature at the University of Nebraska, and was a professor of Renaissance literature at the University of Iowa.

“I should have been exuberant, but I wasn't,” she said.“ I felt all this effort I had put into this subject wasn't going to change the course of history or help humanity.”

It was a letdown fueled in part by her experience following the birth of her first child, when Andreasen contracted puerperal sepsis. The cure, in her case, was five days of hospitalization and IV antibiotics, but in an earlier age it was an infection that was deadly for new mothers.

“I was lying in bed reflecting on the fact that if I'd been born in another day, I would have died,” she recalled.

And so it was that after the publication of her book, she decided to go to medical school.

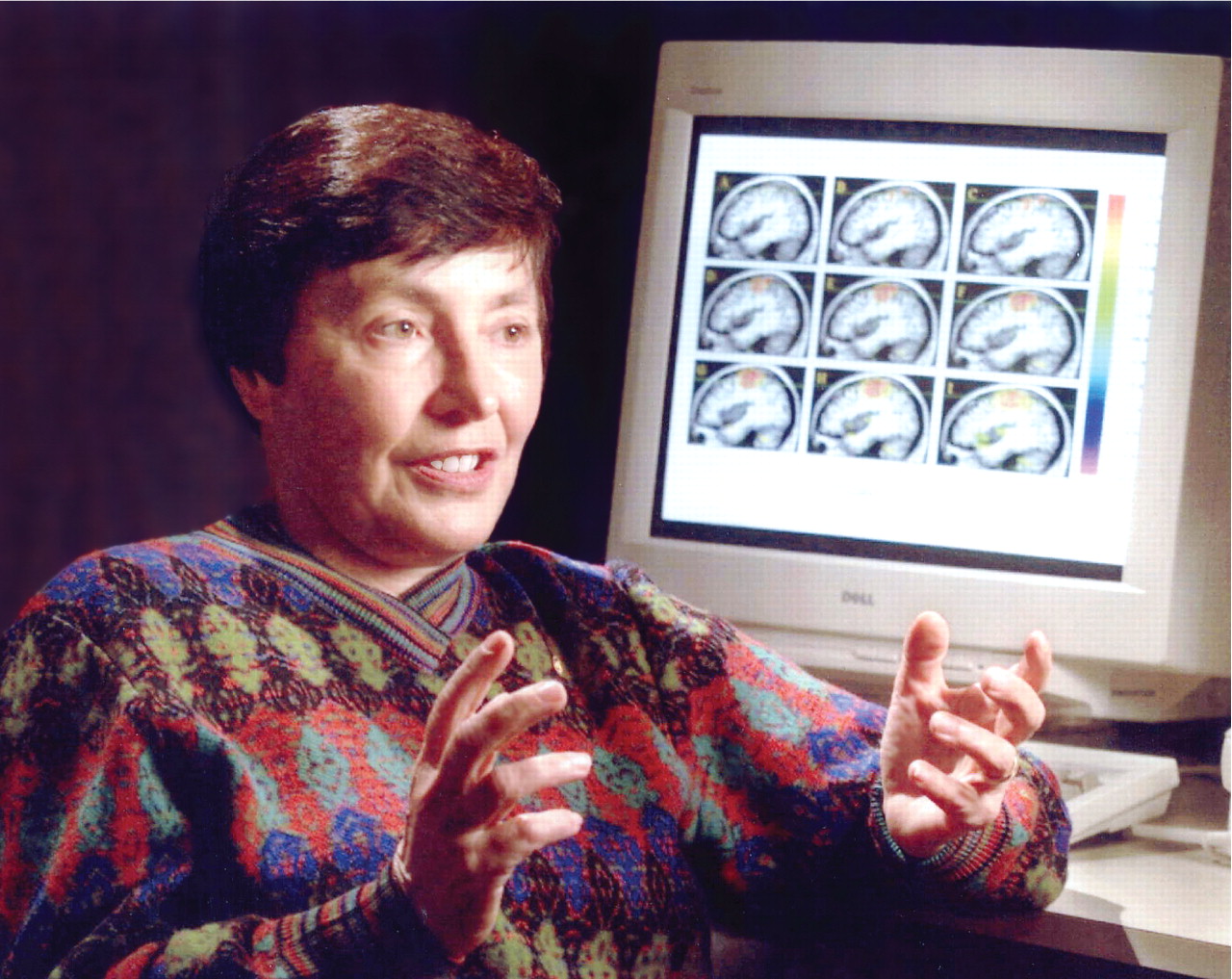

Forty years after the appearance of John Donne: Conservative Revolutionary, Andreasen is recognized as a pioneer in the use of advanced technology for imaging the brain and an expert in the phenomenology and nosology of schizophrenia. She received the President's National Medal of Science award in 2000.

She developed the first scales for measuring the negative and positive symptoms of schizophrenia, and her studies using structural and functional imaging linked brain pathology to observable features of schizophrenia, especially negative and disorganized symptoms.

Andreasen was editor of the American Journal of Psychiatry for 13 years, from 1992 to 2005. As chair of the Schizophrenia Work Group for DSM-IV, she was instrumental in refining the description of schizophrenia in a way that was neurobiologically informed while more fully capturing its clinical reality.

Along the way she has mentored many young investigators who comprise a new generation of schizophrenia researchers.

“Nancy has really followed in the model of Emil Kraepelin in that she starts out by being a keen observer of phenomenology,” said one of those mentees, Michael Flaum, M.D. “Her starting point has always been to say, 'How can we do a better job of describing the phenomenon of schizophrenia in a more reliable way?'

“Nancy's work has helped to turn difficult clinical phenomena into meaningful, measurable data at the neurobiological level using structural and functional imaging, always relating it back to the clinical phenomenology,” said Flaum, an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Iowa and director of the Iowa Consortium for Mental Health.

'I Knew This Was Going to Be My Specialty'

In 1968, at a time when it was still rare for a woman to go to medical school, Andreasen entered the University of Iowa School of Medicine.

From the outset she wanted to have a research career. After her second year she took an elective in psychiatry doing laboratory research on the effects of lithium on coritsol production and worked for the first time with people who had schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

The experience hooked her, and she entered the psychiatry residency at Iowa. “For me the question was, How can the human brain produce such bizarre thoughts and behav iors?” Andreasen recalled. “I knew then that this was going to be my specialty—understanding the brain in living human beings.

“My early work on the brain was based on cortisol, but I realized quickly I wasn't going to learn what is going on in the brain by measuring peripheral metabolites,” she said. “My window into the brain was going to have to be cognitive neuroscience, or what was then called psychology.”

Her first stop after residency was as a clinician. A friend who was director of the burn unit at the University of Iowa Hospital told Andreasen that they were now saving people who had burn injuries on over 80 percent of their bodies and discharging them with severe disfigurements.

Would she come and work as a staff psychiatrist on the unit?

“He said to me, 'They go through this horrible agony. Are we really doing them a favor? What is the long-term impact on their lives?' “

So Andreasen spent the next two years working with a four-person team, making rounds and wrestling with such excruciating questions as when do you let someone whose face has been catastrophically burned look at himself or herself in the mirror?

But her interest in schizophrenia persisted during and after her residency training when she joined the faculty at Iowa. In working with patients with schizophrenia, she observed early on that an especially crucial factor was their inability to relate to others in a meaningful way. Her department chair at Iowa, George Winokur, M.D., was a stickler for measurable data, and when Andreasen tried to impress on him the importance of emotional blunting as a symptom, he insisted there was no way to quantify it.

So she set about doing just that; she developed an instrument for measuring emotional blunting, a precursor to the scales she would develop later for assessment of negative and positive symptoms.

CT Scans Revolutionized Research

By the mid 1970s the first CT scans began to appear, and cognitive neuroscience would never be the same. “When I saw one for the first time, I thought, now we finally have a tool to measure the brain.”

In the March 1982 American Journal of Psychiatry, Andreasen was lead author of a study using CT images to show an association between ventricular enlargement in people with schizophrenia and negative symptoms.

“These findings,” the study concluded, “suggest that combining a measure of brain structure with the clinical picture may provide a useful new approach to the classification of schizophrenia.”

Then in the mid 1980s, Andreasen saw the first MRI scan of the brain.“ It was exquisite, and I thought, this is going to be my tool for years to come,” she said.

Over time she would publish dozens of papers relating structural and functional measurements of the brain to clinical features. In the February 1986 Archives of General Psychiatry, she and colleagues published the first quantitative MRI study done in psychiatric patients, showing that people with schizophrenia had decreased cerebral and frontal-lobe size.

And a December 1992 study in the Archives used functional imaging (SPECT) to examine the brains of study subjects while doing a task (the Tower of London) believed to be a stimulant of the frontal cortex. That study examined three samples: neuroleptic-naive schizophrenia patients, non-naive schizophreniapatients who had been relatively chronically ill but were medication free for at least three weeks, and healthy volunteers.

The study found that decreased frontal-lobe activity is related to negative symptoms and is not a long-term effect of neuroleptic treatment or of chronicity of illness.

By examining different subsets of patients, that study addressed a central problem in imaging studies—the heterogeneity of subjects; because patients in studies have a range of symptoms and characteristics, the studies have produced different, sometimes conflicting results.

What the Future Holds

Andreasen says the future of schizophrenia research is in combining gene studies with accurate selection of specific phenotypes. In this way, researchers can more accurately match genetic variation with a specific symptom of interest.

“The wave of the future is to integrate genomics into systems-level measurements such as those we obtain from neuroimaging,” she said.“ So you take a polymorphic gene that has several different alleles and determine whether that variation is related to some interesting measure at the level of the whole human system.”

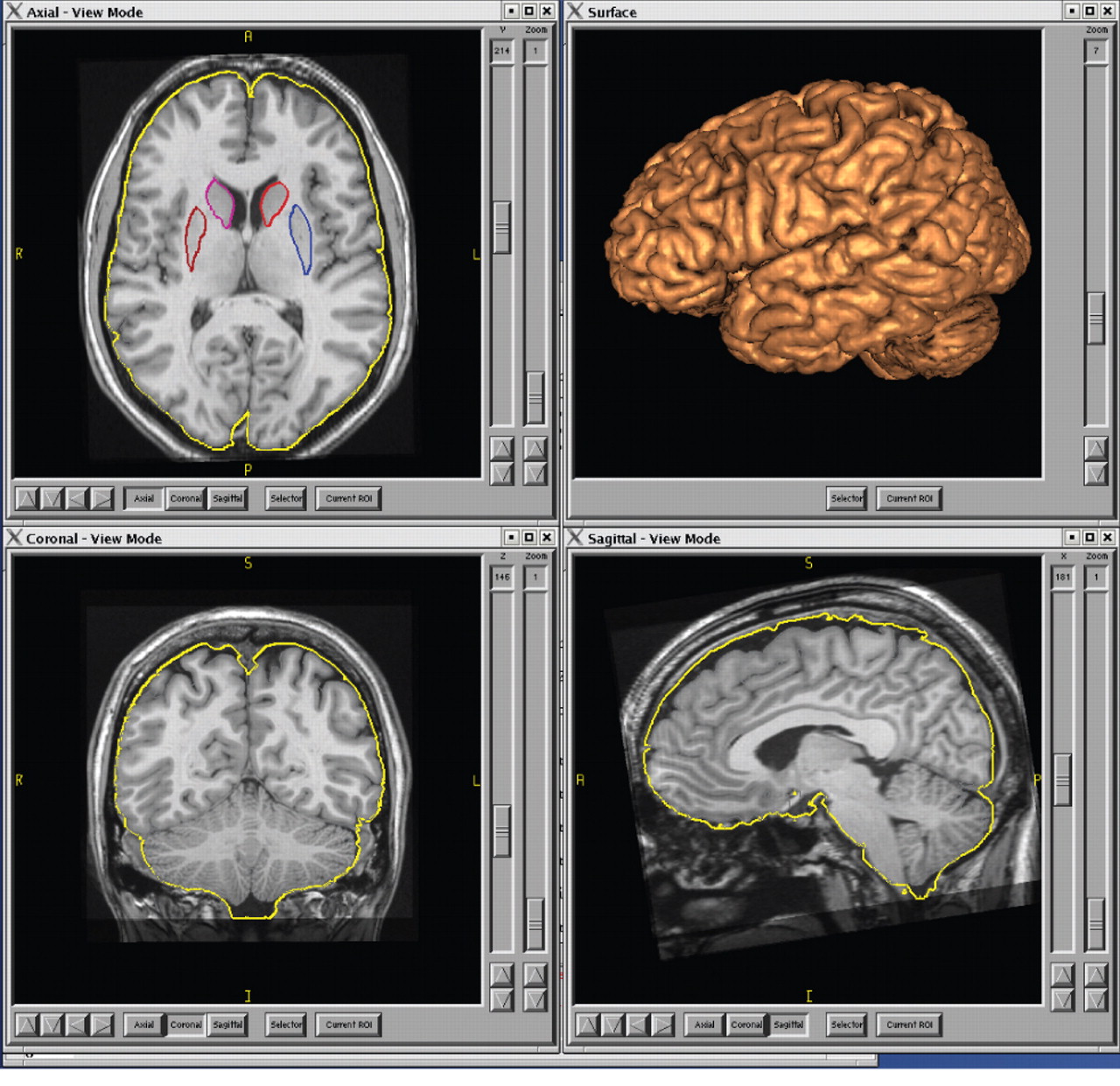

Today Andreasen continues to push the boundaries of imaging technology and is leading a team of investigators at Iowa in the development of computer software, known as BRAINS2, for three-dimensional brain imaging.

The English literature scholar who wrote John Donne: Conservative Revolutionary, offered in that book a new take on the“ metaphysical” poet whose late-life turn to the Anglican faith had traditionally been viewed as a break with the “revolutionary” ardor reflected in his earlier erotic love poems.

Instead, Andreasen suggested, the earlier love poems were satirical, reflecting a consistency of temperament throughout the poet's career—hence, a conservative revolutionary.

Similarly, the researcher who seized on the revolutionary tools of imaging to measure symptoms and who translated clinical phenomena into“ meaningful, measurable data” was also a traditionalist steeped in the humanities who sought to relate the data back to clinical phenomenology—to the individual patient.

In an article in the January Schizophrenia Bulletin, she wrote that “since the publication of DSM-III in 1980, there has been a steady decline in the teaching of careful clinical evaluation that is targeted to the individual person's problems and social context....”

For schizophrenia, A ndreasen told Psychiatric News, this has meant a focus on specific symptoms at the expense of the underlying neurocognitive impairment that renders the patient unable to comprehend, or be comprehensible to, the environment.

“If we teach our young psychiatrists that schizophrenia is delusions and hallucinations—which is what they are learning based on the DSM—we are leading them down a blind alley,” she said.“ The essence of the disease is this profound change in the cognitive function that enables a person to relate to the world.” ▪