A number of people may experience psychotic symptoms even if they do not have a full-blown psychotic disorder, various studies have suggested. For example, the first National Comorbidity Survey, published in 1996, found that 28 percent of Americans had experienced psychotic symptoms at some point in their lives. European studies placed the percentage between 6 percent and 18 percent.

However, none of these studies evaluated how many people experience such symptoms over the long term. So Wulf Roessler, M.D., a professor of clinical and social psychiatry at the University of Zurich in Switzerland, and his colleagues decided to do so.

Results from their 20-year investigation appeared in the May Schizophrenia Research.

Roessler and his group started with 4,600 19- or 20-year-olds representative of their age group in the Zurich area. Each was mailed and asked to fill out the Symptom Checklist 90-R (SCL90-R). The SCL90-R is a comprehensive self-report questionnaire containing 90 questions, covering a broad range of psychiatric symptoms. From the individuals who responded, the researchers selected 591 to participate in their 20-year longitudinal study. Two-thirds of them had scored high in psychiatric symptoms on the SCL90-R, and the remaining one-third had scored within the normal range. The reason why they conducted their inquiry in this fashion, Roessler explained to Psychiatric News, was “because it is a time- and money-saving way to conduct longitudinal studies and because one wants to increase the chances of assessing rare symptoms.”

When the subjects were aged 21, 23, 28, 30, 35, and 41, they were asked not only to fill out the SCL90-R, but to undergo a semistructured interview. This way the scientists could not just plot their experiences with various psychotic symptoms, but also diagnose them, according to DSM criteria, for schizophrenia. Out of the initial 591 subjects, 372 completed the entire study.

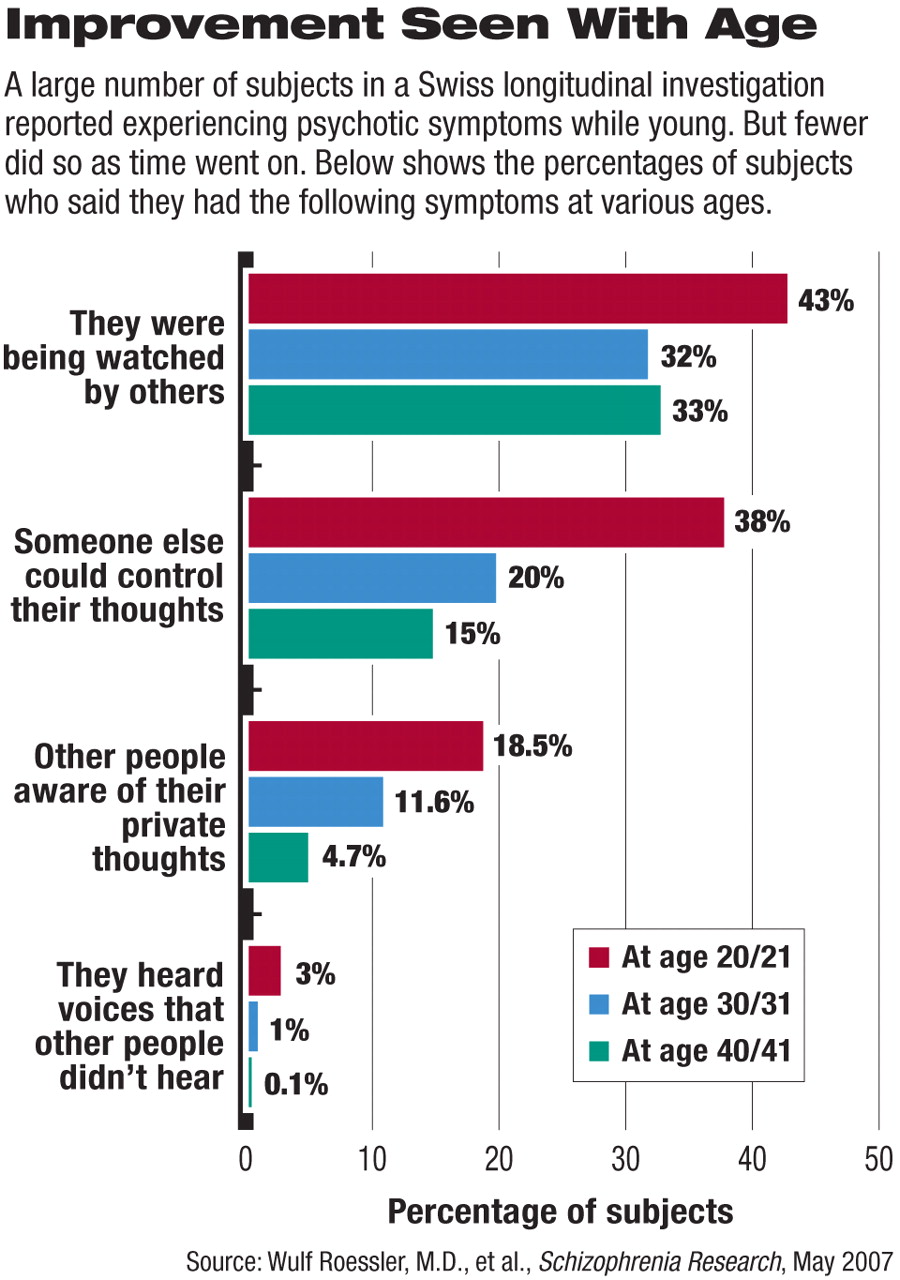

Roessler and his team found that a large proportion—58 percent—reported having experienced psychotic symptoms at one time or another. For example, at age 21, 38 percent reported that someone else could control their thoughts, and 19 percent reported that other people were aware of their private thoughts. At age 30, 30 percent reported that they felt lonely even when with other people. At age 41, about 33 percent said they were being watched by other people.

As time went by, the subjects experiencing psychotic symptoms could generally be placed in two groups—those with the nuclear symptoms of schizophrenia such as auditory hallucinations and thought-broadcasting, and those with schizotypal symptoms such as odd beliefs, suspiciousness, and a reduced capacity for close relationships. Nonetheless, 6 out of 10 subjects who had experienced a consistently high level of schizotypal symptoms also experienced a continuously high level of schizophrenia nuclear ones, and those who remained highly symptomatic in either domain experienced a lot of difficulties in their lives on factors such as partnerships, careers, or contact with the justice system.

Results Extrapolated

The researchers then extrapolated their findings to the general Swiss population; that is, they gave more weight to results from subjects who had initially scored normally on the SCL90-R than to results from subjects who had initially scored at or above the 85th percentile. Using this procedure, they found that 6 percent of the general population experienced schizophrenia nuclear symptoms, and 3 percent experienced schizotypal symptoms at some point in their lives.

“This study is the most recent in a growing number of reports that document a much higher prevalence of subthreshold psychotic experiences in the general population than was previously thought to be the case,” Ronald Kessler, Ph.D., told Psychiatric News. In addition to being a professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, Kessler headed the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (Psychiatric News, July 15, 2005).

“Importantly,” he added, “this study also documented considerable consistency in these experiences over a two-decade follow-up period.... We have long known that more common emotional disorders, such as depression and phobia, are at the upper ends of continuous distributions, with substantial proportions of the population having subthreshold manifestations. It is striking to find the same is true for psychotic experiences.”

Surprises Appear Among Results

Yet more provocative results emerged from this investigation, Roessler noted.

For example, while a considerable number of subjects reported psychotic symptoms throughout the 20-year period, fewer tended to do so as time went on. Roessler admitted that he wasn't sure of why this occurred, “But what we do know from the epidemiology of schizophrenia and psychotic disorders is that we would expect the highest rates of psychotic symptoms to occur in the 20s, with a constant decline over the two decades of our observation period.”

Also, individuals who reported continuously high levels of the nuclear symptoms of schizophrenia often had used marijuana in adolescence. Indeed, use of marijuana at age 20 or 21 was the most prominent predictor for a continuously high level of schizophrenia nuclear symptoms over the next 20 years. Furthermore, the odds ratios were higher in frequent users, indicating a dose-response relationship.

In contrast, individuals who reported a continuously high level of schizotypal symptoms often had experienced troubled childhoods, suggesting that childhood adversity might be a risk factor for them.

The report, Kessler asserted, “raises important questions about the... implications of extending research on early preventive intervention with incipient cases of psychosis to include the substantial number of people with stable subthreshold symptoms.”

Roessler agreed. “Our study gives new impetus to the discussion about early detection and treatment of schizophrenia. It has been considered unethical to treat persons below the diagnostic threshold. This should be re-discussed considering the significant impact of these subthreshold symptoms.”

No easy answers on when treatment should be offered, however, could be gleaned from this study. For as Roessler pointed out, “We did not find one person acquiring full-blown schizophrenia. The conclusion is that the 'psychotic states' we identified in our subjects stand for themselves. They are not just pre-forms of schizophrenia. They are part of the spectrum disorder from schizotypal personality disorders to full-blown schizophrenia.”

The study was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation.

An abstract of “Psychotic Experiences in the General Population: A Twenty-Year Prospective Community Study” can be accessed at<www.sciencedirect.com> by clicking on “S” under “Browse by title,” then“ Schizophrenia Research.” ▪