Rates of the diagnosis and pharmacological treatment of depression among children and adolescents dropped sharply after October 2003, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued its first public health advisory informing health care professionals of an increased risk of suicidality among youngsters taking antidepressants.

These findings, which appeared in the June American Journal of Psychiatry, have heightened the concerns of researchers and clinicians alike that suicide rates among untreated children and adolescents will rise unchecked. In fact, a study published in the February Pediatrics revealed an 18.2 percent increase in suicide from 2003 to 2004 among youngsters under the age of 20 (Psychiatric News, March 2).

“We are seeing a treatment option that has been found to be safe and effective not being used for an illness that has very serious health and social consequences” for young people, first author Anne Libby, Ph.D., told Psychiatric News. “We are placing kids with untreated depression at risk for suicide.”

Libby is an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado.

Using the PharMetrics Patient-Centric Database, Libby and her research team examined more than 60,000 paid claims for patients aged 5 to 18 who had been diagnosed with new episodes of depression between October 1998 and September 2005.

The database includes paid medical, specialty, facility, and pharmacy claims from more than 85 managed care plans and 4 million enrollees across the nation, according to the report.

The researchers traced the rates of depression diagnosis, antidepressant prescription patterns, and the use of psychotherapy and other treatments for pediatric enrollees with depression over the seven-year period.

Even Diagnostic Rates Dropped

Libby and her colleagues noted that the FDA first raised a red flag about antidepressants in October 2003 when it issued a public health advisory about a possible increased risk of both suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in children and adolescents taking antidepressants.

The researchers selected the 2003 advisory as the “policy action of interest,” according to the report, and measured trends in diagnosis and antidepressant prescription in relation to the advisory's release.

The rate of new episodes of depression diagnosed among male and female enrollees steadily increased from 1998 to 2004. For instance, from 1999 to 2004, the rate of depression diagnoses increased from 3 to 5 per 1,000 youngsters, according to the report. By September 2005, however, the rate was back to 1999 levels, which was a “significant deviation from the historical trend.”

After analyzing the findings by gender, the researchers found that the historical trend from 1999 to 2004 would have predicted that 3.8 per 1,000 boys be diagnosed with a new episode of depression; however, the observed rate in September 2005 was only 2.3 per 1,000 boys.

For girls, the predicted rate of new depression episodes was also higher than the actual rate: 3.5 per 1,000 girls had a new episode of depression in September 2005, whereas the predicted rate based on the historical trend was 6 per 1,000.

The researchers not only noted a drop in the number of new episodes of depression diagnosed among children and adolescents, but also discovered telling shifts in the types of providers diagnosing the new episodes. In the preadvisory period, nonpediatrician primary care physicians diagnosed about 24 percent of all new episodes of depression, while psychiatrists diagnosed more than 22 percent.

Researchers predicted that by September 2005, almost 40 percent of all new episodes of pediatric depression would be diagnosed by primary care doctors, but the actual figure was only about 27 percent. In contrast, psychiatrists diagnosed a higher percentage of episodes than was predicted—24.2 percent versus a predicted 20.4 percent.

The fact that primary care doctors diagnosed fewer new episodes of depression in children and adolescents than was predicted while psychiatrists diagnosed more cases may indicate that nonpsychiatrist physicians felt that specialty care was necessary after the FDA advisory, Libby speculated.

SSRI Fill Rates Fall Below Projections

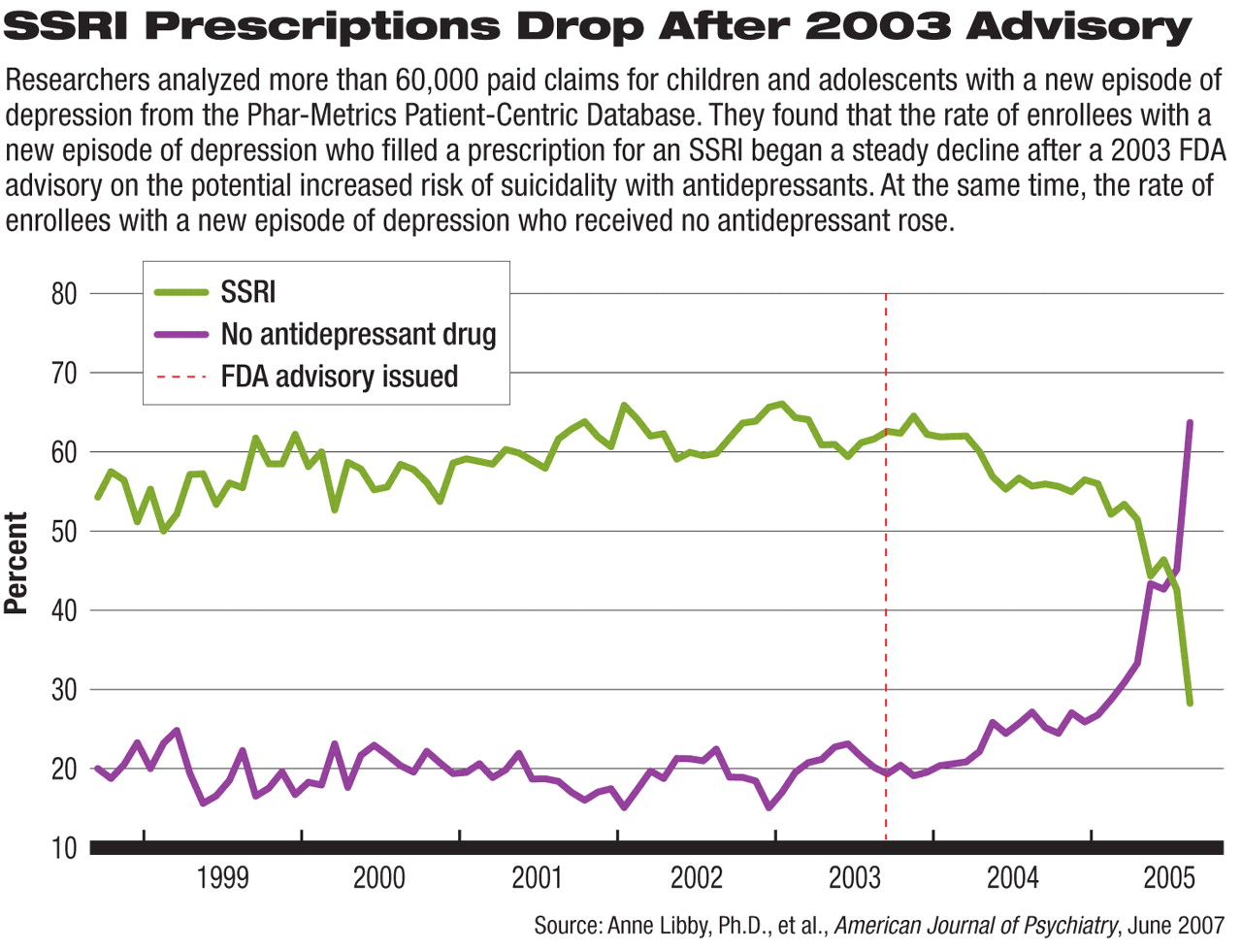

During the preadvisory period, a little over 59 percent of the children and adolescents who had been diagnosed with depression filled a prescription for an SSRI within 30 days of being diagnosed, according to the report. In the postadvisory period, the average was 55 percent.

Based on preadvisory trends, Libby and her colleagues predicted that 67.4 percent of young enrollees with depression would fill prescriptions for SSRIs by September 2005, but found that only 28.6 percent did.

According to Robert Valuck, Ph.D., one of the report's co-authors and an associate professor of pharmacy at the University of Colorado, “we are looking at youth with a new diagnosis of depression, for which FDA-approved treatment exists with fluoxetine and for which clinical guidelines recommend pharmacologic treatment. So arguably, most of these youth should be receiving antidepressants.”

The researchers then examined whether physicians were substituting other forms of treatment for antidepressants, but for the most part, the answer was no. For instance, average annual psychotherapy rates did not change significantly after the initial FDA advisory.

In the Phar-Metrics data, psychotherapy was counted if patients had at least one psychotherapy visit within 180 days of a diagnosis of depression and was not distinguished by type.

However, the findings did buck researchers' predictions based on regression analyses: by September 2005, the observed rate of psychotherapy received by depressed patients (40 percent) was significantly higher than preadvisory trends would have predicted.

“This measure indicates only that patients had at least one visit, and of course one visit does not equal an effective treatment program of psychotherapy,” Libby noted.

Libby and Valuck said they would like to continue to follow diagnostic and antidepressant prescription rates to see if the downward trends continue or whether they turn around over time.

“The fact that we are seeing evidence of a large number of kids with untreated depression is troubling and suggests that they are left at risk for something we have the technology to treat,” Libby said.

“This paper supports previous findings that the FDA black-box warning has had a significant impact on the diagnosis and treatment of depression in children and adolescents,” Darrel Regier, M.D., M.P.H., told Psychiatric News.

Regier is director of the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education and APA's Division of Research.

He also cited an article by Jeff Bridge, Ph.D., in the April 18 Journal of the American Medical Association indicating that the benefits of antidepressants for children and adolescents outweigh the risks of suicidal thoughts and attempts that have been associated with antidepressants.

When these findings are considered in the light of those by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and in other studies that“ child and adolescent rates have increased in concert with declining depression diagnosis and treatment rates, the overall public health impact of the FDA warning needs to be reevaluated,” he said.

“Decline in Treatment of Pediatric Depression After FDA Advisory on Risk of Suicidality With SSRIs” is posted online at<ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/abstract/164/6/884>.▪