Ever since regulatory agencies issued warnings that antidepressant drugs may increase suicidal ideation and behavior in children and adolescents, psychiatrists and mental health professionals have been worried about decreased patient access to adequate treatment.

Recent data from Tennessee's expanded Medicaid program, TennCare, seem to support this concern. Nearly two years after the first warning issued by the U.K. drug regulatory agency, the Committee on Safety of Medicines (CSM), significantly fewer Tennessee children and adolescents were started on antidepressants.

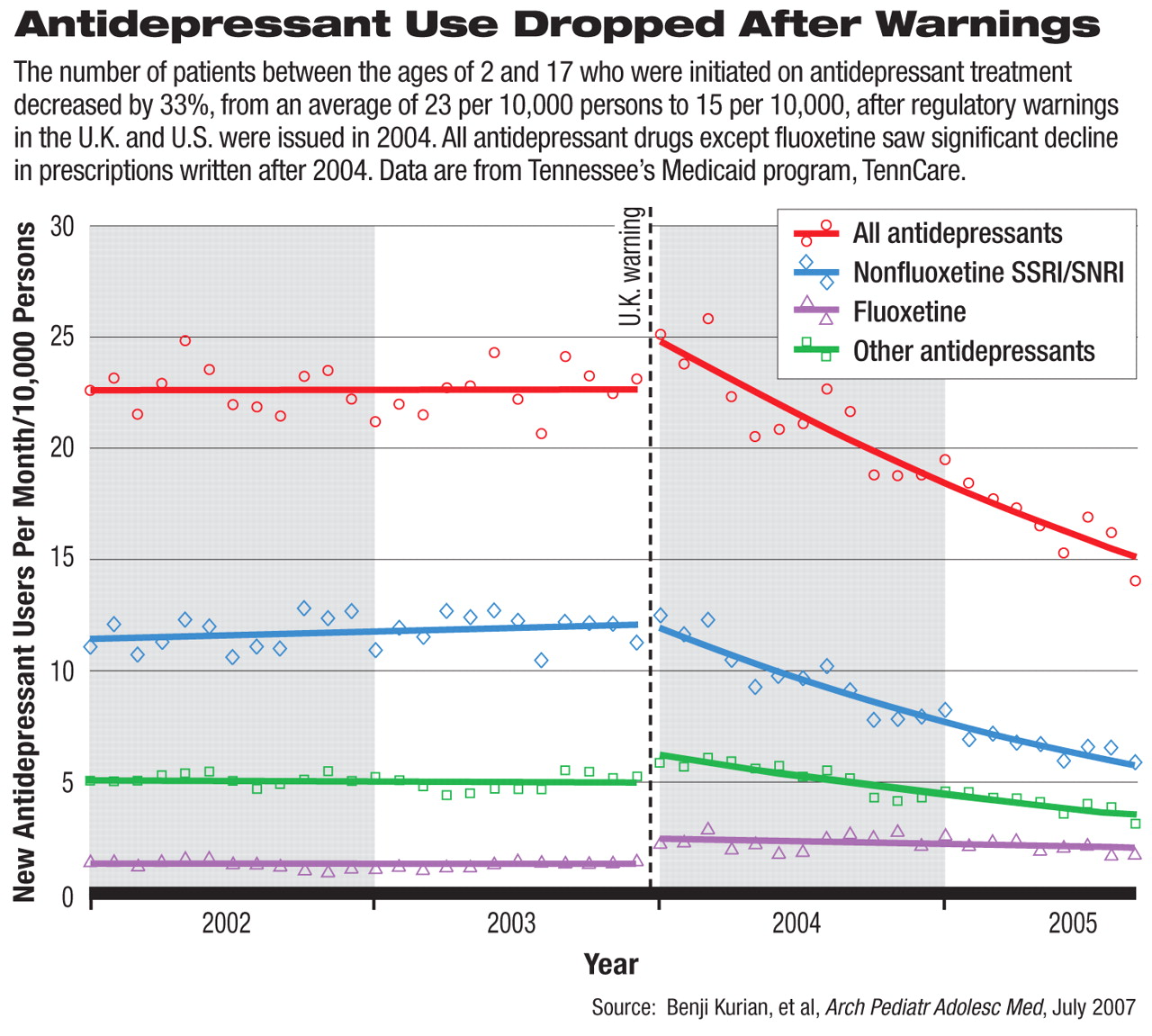

Benji Kurian, M.D., M.P.H, and colleagues at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine analyzed 2002 to 2005 antidepressant prescription patterns in the TennCare database. The population they studied encompassed approximately 400,000 participants between ages 2 and 17 in the state Medicaid program. By September 2005, 12 months after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required black-box warnings on suicide risks in children and adolescents taking antidepressants, the average number of new patients who were put on antidepressants was 15 per month per 10,000 persons. This was a 33 percent drop from the monthly average of 23 per 10,000 persons in 2002 and 2003.

The downward trend in new antidepressant prescriptions began in January 2004 and continued through the end of the study period in September 2005. The number of new prescriptions for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), except fluoxetine, and for selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and other antidepressants decreased compared with the average in 2002 and 2003.

Numbers of new prescriptions for tricyclic and related antidepressants were not significantly changed. However, 60 percent more patients were put on fluoxetine by the end of the study period compared with the two years before the warnings were issued. The authors cited the fact that both the CSM and FDA consider fluoxetine as the preferred pediatric antidepressant. Fluoxetine is the only SSRI with FDA-approved indication for treating depression in pediatric patients.

Not surprisingly, the authors also found the same decreasing trend of any antidepressant prescriptions (including both new and continued prescriptions) filled after January 2004 in the database. However, they observed no sign of increased discontinuation of treatment, indicating that physicians were generally comfortable with maintaining patients' ongoing antidepressant treatment. In addition, the authors found no signs of switching to other psychotropic drugs, as the monthly use of these drugs did not increase significantly in the same periods.

The authors used January 2004 as the cut-off date for the before-and-after comparison, as the period in late 2003 and early 2004 saw an influx of media attention and regulatory warnings on suicide risks associated with antidepressants in younger patients. In December 2003, the CSM concluded that the risk-benefit profile of all nonfluoxetine SSRIs, as well as venlafaxine and mirtazapine, is unfavorable for the treatment of major depression in children and adolescents. In March 2004, the FDA issued a public-health advisory and, in October, required black-box warnings for all antidepressants (including fluoxetine) regarding the increased risks of suicidal thinking and behavior in children and adolescents.

APA and others in the mental health community have voiced concerns that the regulatory agencies' warnings may have unintentionally undermined appropriate and adequate treatment for depression, including but not limited to younger patients (Psychiatric News, January 19, June 15).

“This study confirms what other authors have found—that the warnings have had a dramatic effect on treatment of depression in children and adolescents,” said Darrel Regier, M.D., M.P.H., director of the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education and of APA's Division of Research. Similarly, a previous study by Anne Libby, Ph.D., and colleagues, published in the June American Journal of Psychiatry, showed that the rates of diagnosis and pharmacotherapy of depression among children and adolescents dropped sharply after October 2003.

Does this trend of decreasing antidepressant prescriptions reflect a heightened caution that is appropriate, or is the reduced antidepressant use detrimental to patient care? The authors noted that they were unable to assess the appropriateness of antidepressant prescribing in their data sample. However, an alarming rise in the number and rate of suicide deaths from 2003 to 2004 in youth under age 20 highlighted the urgency of getting a better picture of the state of treatment for depression (Psychiatric News, March 2). “The black-box warnings have brought attention to the need for close monitoring in the use of antidepressants in children,” commented Regier. “What we are concerned about is that patients may not be getting adequate care, such as psychotherapy, when they are not treated with antidepressants. It remains to be seen whether more evidence will eventually show that the risk of untreated depression outweighs the benefits [of the warnings].”

The FDA has recently requested that the warnings about increased risk of suicide be extended to include patients up to age 24 in antidepressant drug labeling (Psychiatric News, June 1). Meanwhile, the FDA also told manufacturers to add wordings on the risk of suicide associated with depression in these black-box warnings, which may be a step toward giving more balanced guidance on this complex issue.