A study of more than 200,000 veterans adds to the evidence that treating depression reduces suicide attempts, even among young adults.

The results contrast with findings by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that suicidality rises after treatment in young people aged 18 to 25. Those findings led the agency to expand its black-box warning recently (Psychiatric News, June 1).

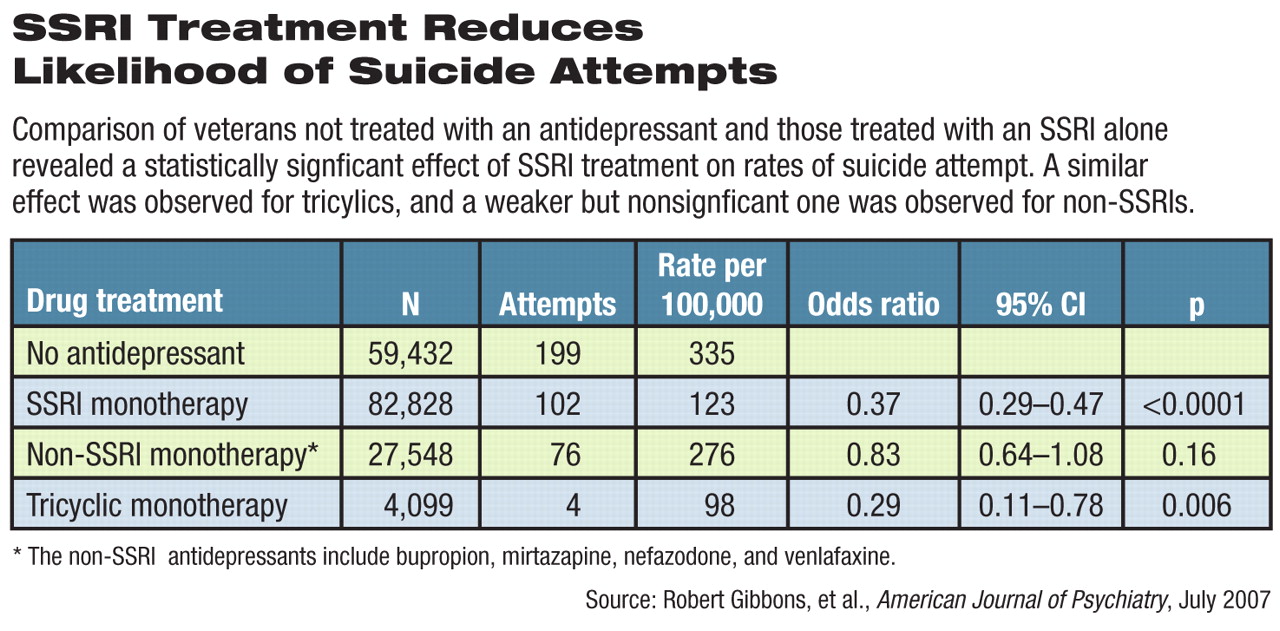

“The risk of suicide attempt among patients treated with an SSRI was about one-third that of patients who were not treated with an SSRI,” wrote the authors in the July American Journal of Psychiatry.

Their conclusions held for all age groups, they said. “In contrast to the FDA's findings, our analysis of the VA data indicates that these protective effects also apply to patients in the 18- to-25-year-old age group.”

Using data from the Veterans Health Administration, researchers led by Robert Gibbons, Ph.D., director of the Center for Health Statistics and a professor of biostatistics and psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, examined the relationship between antidepressant treatment and suicide attempts in a group of 226,866 veterans with depression. These patients had experienced depressive or unipolar mood disorders in 2003 or 2004, had at least six months of follow-up, and had no history of such disorders or antidepressant treatment from 2000 to 2002.

Outcomes were based on suicide-related diagnostic codes in patient records, but not cause-of-death information.

About 26 percent of the patients (59,432) were not treated with antidepressant medications. The rest were treated with SSRIs, newer non-SSRIs (like bupropion, mirtazapine, nefazadone, or venlfaxine), or tricyclic antidepressants. Some had received combined treatment.

SSRI treatment, alone or in combination, resulted in a rate of 364 suicide attempts per 100,000 patients. The rate for all other patients, with or without treatment, was 1,057 per 100,000. More specifically, the rate for patients taking SSRIs was 123 per 100,000, compared with 335 per 100,000 among untreated patients, an odds ratio of 0.37 (see

table). Rates of suicide attempts were cut nearly in half after treatment began.

“Our analyses of VA data are consistent with the hypothesis that treatment with SSRIs lowers the risk for suicide attempt in adults with depression and do not support the hypothesis that SSRIs increase the risk of suicidal behavior in adults,” the researchers concluded.

Their data on the 18- to-25-year-old cohort throws some light on the FDA's analysis and its decision to expand its black-box warning to those patients, Gibbons and his colleagues said.

The attempted-suicide rate in this VA age cohort treated with SSRIs was 477 per 100,000, close to the FDA's finding of 551 per 100,000. However, the VA study found a rate of 1,368 per 100,000 attempts among untreated depressed 18- to-25-year-old patients, compared with the FDA rate of 269 per 100,000.

The difference between this study and the FDA's number may be due to the selection of patients with lower risk of suicide attempts who were enrolled in the controlled randomized trials on which the agency based its analysis.

Clinical trials more congruent with real-world patients and contexts should enroll subjects that include more of the high-risk patients found in clinical practice, said David Brent, M.D., a professor of psychiatry, pediatrics, and epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, in an accompanying editorial.(see related article

Suicide Attempts Decline With Psychotherapy or Antidepressants.)

“Only by empanelling depressed patients at significant suicide risk into randomized trials and then systematically assessing the impact of treatment on suicidality and depression will we be able to delineate the effects of antidepressants and psychotherapy on depression and suicide risk,” Brent said.