Mental health courts offer an alternative to sending still more people with mental illness to jail. Judges, public defenders, district attorneys, case managers, therapists, probation officers, and psychiatrists together closely supervise defendants selected for these diversion programs, helping with housing, medical care, psychotherapy, education, and job training or coaching.

The goal is to prevent these defendants from committing more crimes and to help them find a place in the community. Offenders who complete the program can have charges dropped or expunged (Psychiatric News, April 21, 2006).

About 90 mental health courts operate around the country, yet little is known about the extent to which they reduce the chances of a defendant's committing another crime.

Now a study of the mental health court in San Francisco documents reduced levels of recidivism, as measured by the time to re-offending, although questions remain about what accounts for outcomes and who gets to participate in the programs.

Dale McNeil, Ph.D., a professor of clinical psychology in the Department of Psychiatry, and Renée Binder, M.D., a professor in residence in the Psychiatry and the Law Program at the University of California, San Francisco, compared 170 criminal defendants who entered the mental health court with 8,067 other offenders who received treatment as usual, consisting of passage through the criminal justice system. All subjects had been diagnosed with some mental illness, and two-thirds were charged with felonies. Defendants selected for diversion included a higher proportion of persons with developmental disabilities or severe mental illness—like schizophrenia, delusional disorder, or bipolar disorder—than the control group.

The researchers used a propensity weighting system to overcome nonrandom assignment and intention-to-treat analysis to include all offenders enrolled in the program, not just those who completed its requirements.

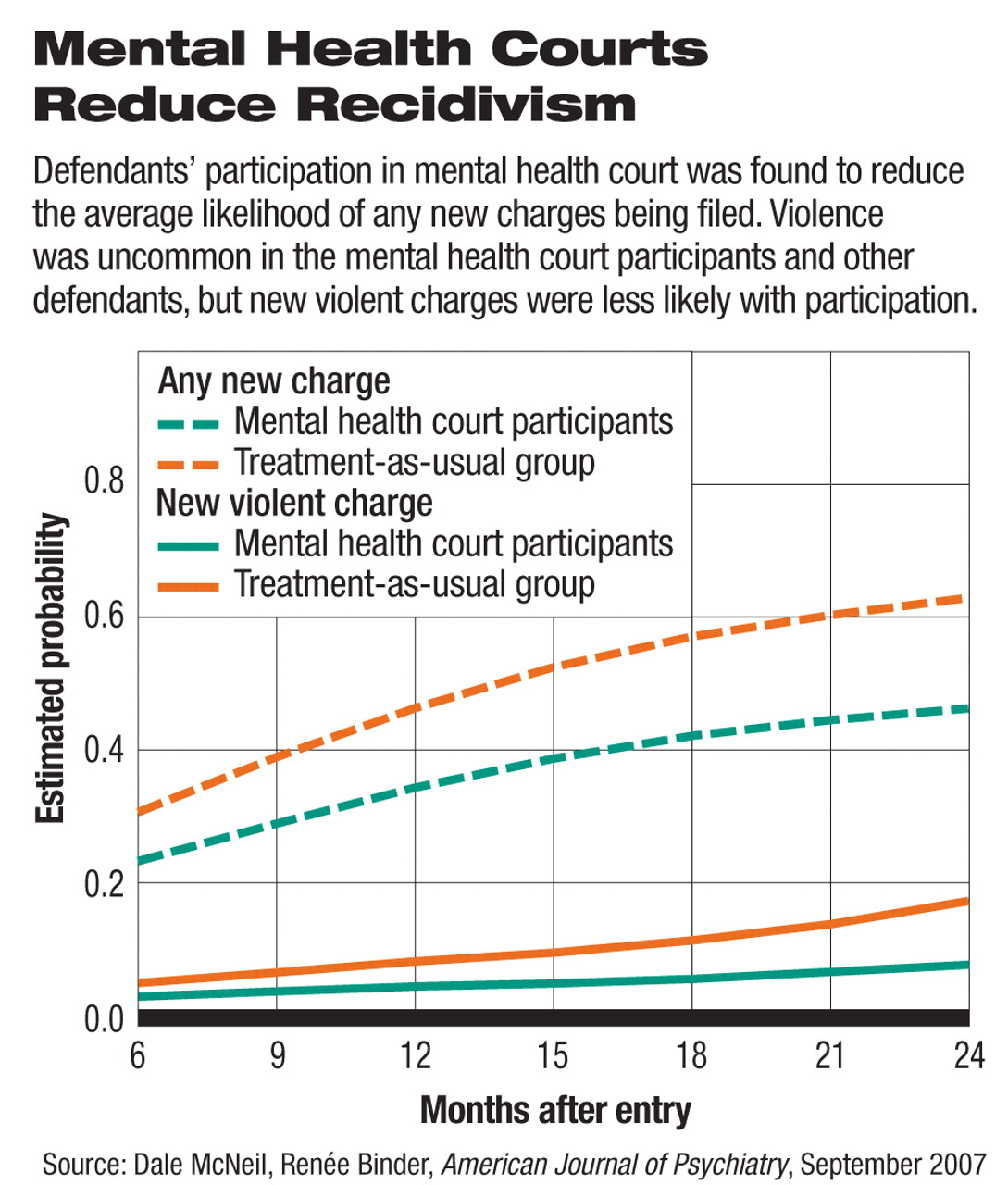

Participation in the mental health court program predicted a longer time before offenders faced any new charge or a new violent charge, wrote McNeil and Binder in the September American Journal of Psychiatry.

After at least six months of follow-up, 81 (48 percent) of the enrollees had completed the program, 45 (26 percent) were still in it, and 44 (26 percent) had left, whether voluntarily, for noncompliance, or other reasons. The mental health court graduates remained at a lower risk of recidivism even after they left the court's supervision, according to follow-up analysis.

At 18 months, mental health court participants were 26 percent less likely to be charged with any new crime and 54 percent less likely to be charged with a violent crime, they said (see chart).

Their findings, said McNeil and Binder, “provide evidence of the potential for mental health courts to achieve their goal of reducing recidivism among people with mental disorders who are in the criminal justice system.”

Furthermore, since many defendants in the San Francisco program were charged with violent crimes or felonies, results with this more-difficult population argued for expanding the use of mental health courts beyond individuals who have committed minor offenses, as is the case in some other areas, they said.

Other studies have shown that outcomes vary little between violent and nonviolent offenders or for those diagnosed with more severe illness, said mental health court expert Henry Steadman, Ph.D., of Policy Research Associates in Delmar, N.Y., in an interview with Psychiatric News.“ No research shows that a particular type of person does more poorly.”

Steadman directed a study of 21 mental health court programs sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. He found that 42,518 screenings, assessments, and evaluations resulted in 32,917 decisions about whether to divert them to a treatment program. Only 2,001 of those decisions recommended diversion to mental health courts, and 1,237 of those were accepted by judges.

Although many decisions were needed to divert a few individuals, ultimately, disproportionate groupings by age, race, and gender predicted those chosen to take part.

Enrollees were more likely to be older, white, and female, wrote Steadman in the study published in the August Psychiatric Services.“ That could represent bias, or it could result from the mechanism of assessment.”

An array of people feed information into the system, he said—prosecutors, judges, mental health experts, public health nurses in the jails—making it hard to tease out the source of any overrepresentation of a particular demographic.

“I speculate that the people selected are seen as less threatening to the community, but the community needs to take a chance on a wider group,” he said.

The study did not look at clinical data or outcomes.

These mental health courts may have benefits for society that go beyond just reducing crime. A recent study, described as the first of its kind, of 352 defendants by the RAND Corporation in courts in Pennsylvania,“ Justice, Treatment, and Cost,” found that participation in the jail-diversion program resulted in an increased use of mental health services and a decrease in jail time during the first year after entry into the program. Higher mental health care costs were almost balanced by the reduced costs for keeping the individual locked up. A two-year follow-up found a“ dramatic” reduction in jail costs, although most of that came at the end of the second year, as mental health care costs leveled off.

Steadman agreed with McNeil and Binder that more intensive research is needed to support the case for mental health courts.

“All case studies show promising results,” he said. “Now we need to use the same research methods in many different courts and look at for whom mental health courts work. What are their demographics, their social history, and their clinical history?”

The RAND report, “Justice, Treatment, and Cost,” is posted at:<www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR439/>.▪