That soldiers die in the line of fire in wartime is a sad, but expected, fact of military life. When they die by their own hand, however, it is another matter.

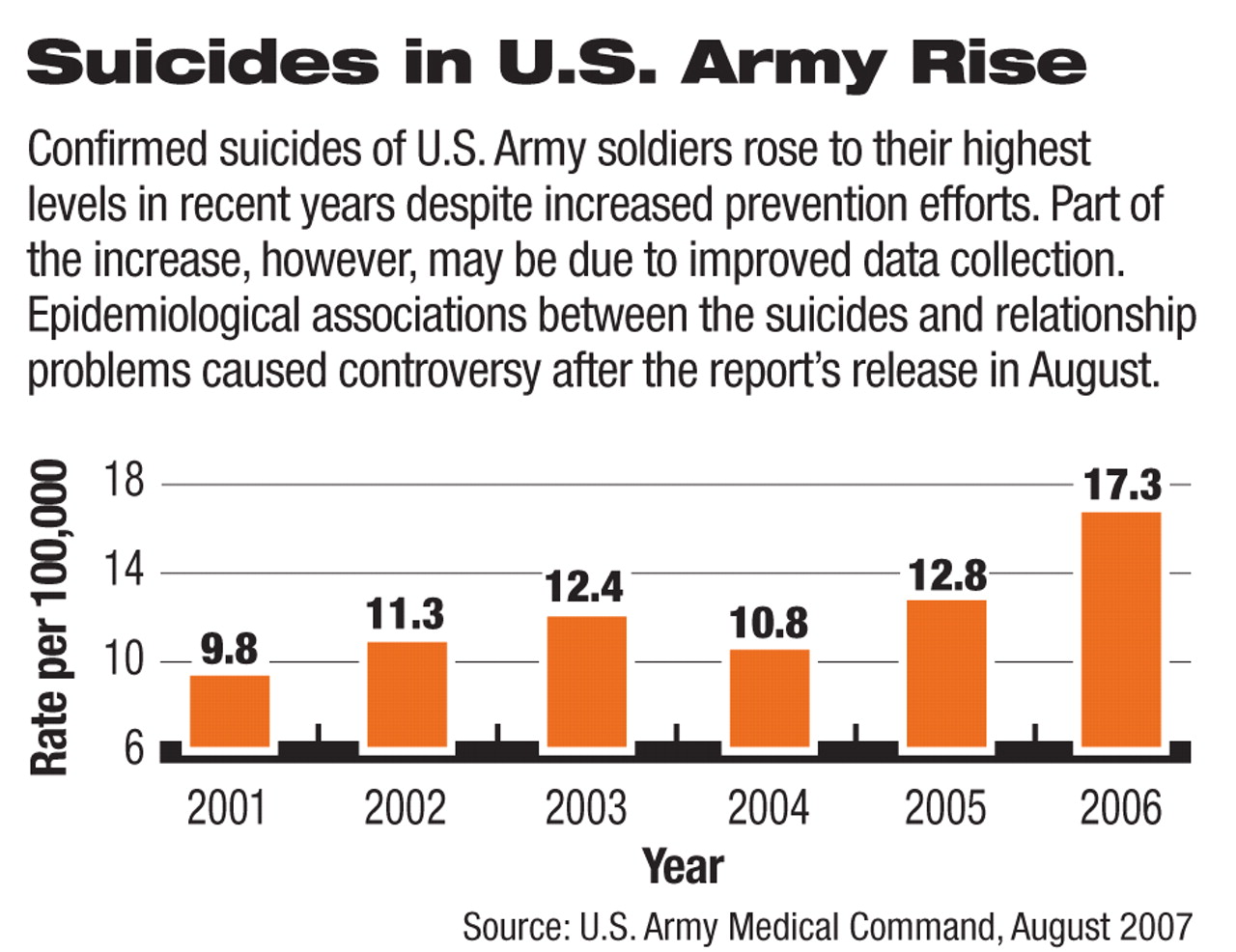

The U.S. Army announced in August that 99 soldiers committed suicide in 2006. That translates to a rate of 17.3 per 100,000. There were 948 soldiers who attempted suicide.

The completed suicides represented a jump over previous years in both absolute numbers and suicide rate. There were 67 suicides in 2004 (or 10.8 per 100,000 soldiers) and 87 in 2005 (12.8 per 100,000) (see graph).

As of June 30 of this year, there were 44 suicides among active-duty soldiers (including reserves and National Guard), 17 during deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan.

Although data had been gathered and analyzed for 2005, the 2006 report was the first using a new reporting system to be made public, said Col. Elspeth Ritchie, MC, psychiatry consultant to the Army surgeon general.

The Army has long gathered data on suicide to guide suicide prevention efforts, Ritchie told Psychiatric News.

The psychological autopsy was originally the method of choice for determining a cause of death, but its narrative form meant it could not be analyzed by computer. The Army Office of Health Affairs decided in 2001 that it would be used only in equivocal cases of suicide or homicide.

In 2004 the Army began using the Army Suicide Event Report (ASER)—a standardized, 12-page, Web-based report—to collect data on suicide-related events that result in death, hospitalization, or evacuation. These events include both suicide attempts and completed suicides. The number of attempts rose from 2005 to 2006, too, but that may be partly due to more thorough reporting, said Ritchie.

Not all events result in immediate ASER notifications to the Army's Suicide Risk Management and Surveillance Office at Madigan Army Medical Center in Tacoma, Wash., although the Army has pushed commanders and others to file the reports promptly. Some delays result from extended investigations by either the service's Criminal Investigation Division, which scrutinizes all completed suicides, or the Armed Forces Medical Examiner's Office. The Army analyzed data from the 85 ASERs for 2006 received by March 1, 2007. (Information released after the Army released its report raised the official number of completed suicides in 2006 to 101.)

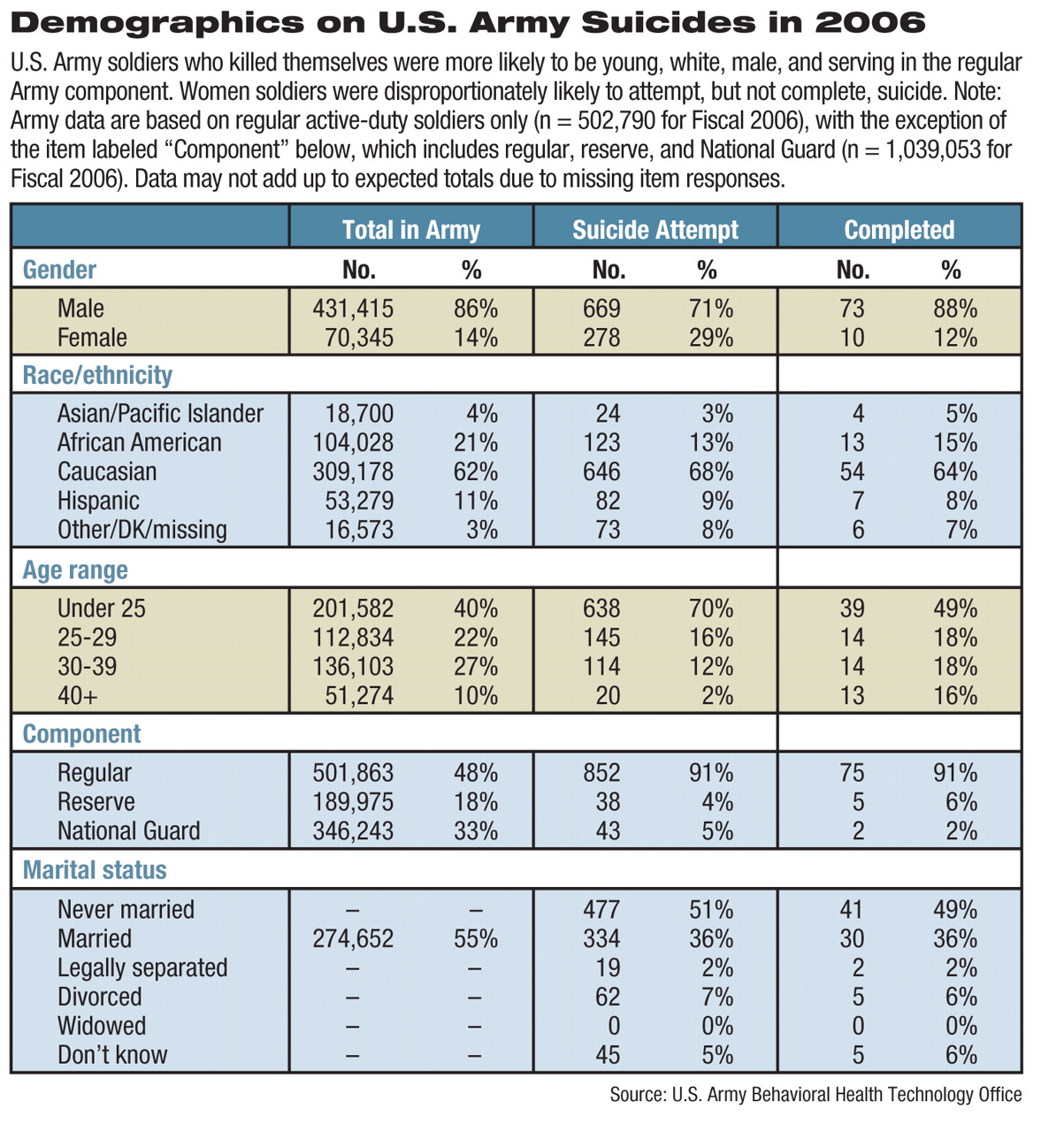

In 2006 overall age-adjusted suicide rates for 85 active soldiers (excluding the National Guard or Reserve) were slightly lower than those in the general population. Once adjustments were made for gender, the rate for male soldiers remained lower than that for U.S. men aged 17 to 45, but the rate for women soldiers was higher than that for their age group.

The Army report included a number of factors linked to soldiers' suicides. Firearms (either military or personal) were used in 71 percent of the completed suicides, but nonfatal attempts most often involved overdoses or self-cutting.

War-Zone Setting Not Determinant

The most common setting for suicide in 2006 was in a “garrison duty environment,” that is, a base located away from war zones.

“I can understand why returning to garrison duty might increase the chances of suicide,” said Paul Ragan, M.D., an associate professor of psychiatry at Vanderbilt University and a former Navy psychiatrist who served during the Gulf War in 1991, in an interview.

“Military units are structured environments and provide an immediate support group that may dissolve back in garrison,” he said.“ Sometimes bad news gets held off until you return home.”

There were 24 suicides among soldiers serving in Iraq and three in Afghanistan in 2006, almost one-third of the 85 ASERs analyzed.

Moreover, 52 of the soldiers whose suicides were analyzed (62 percent) had served at least once in active theaters of war—Iraq, Afghanistan, or Kuwait. Numbers were too small to evaluate risk of multiple deployments to war zones. The Army found an increased, but not significant, trend toward suicides in the early months of deployment. There was some suggestion that exposure to combat increased risk after leaving the war zones, but this, too, was inconclusive.

By comparison, the Marine Corps, a smaller force with roughly similar combat exposure but different deployment patterns, recorded 24 suicides in 2006, a rate of 12.4 per 100,000. Four of those suicides occurred in the war zones.

Some epidemiological patterns emerged from analysis of the data, although the numbers—and possible conclusions—vary owing to incomplete responses and missing data, said Bentson McFarland, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry, public health, and preventive medicine at Oregon Health and Science University, in an interview.

“Rates appear to be based on Armed Forces Medical Examiner reports, whereas the more detailed tables are based on the completed questionnaires,” he said. “This form of reporting is not uncommon.”

Given that caveat, the report said that young, unmarried, junior enlisted, white soldiers were most likely to complete suicide. Suicide completers were less likely to belong to ethnic minority groups.

“The Army numbers of completed minority suicides are very small,” said McFarland. “But it is unlikely there would be statistically significant differences between Army and national data” for completed suicides by members of minority groups.

Search Is On for Risk Factors

Overall, 55 percent of soldiers are married, but married soldiers accounted for only 36 percent of completed suicides. Marital status varied depending on location, though. Among troops who killed themselves in theaters of war, only 30 percent were married, while 52 percent of completers outside the war zones were married, indicating some protective effect of marriage while deployed.

The Army looked for other potential risk factors among the troops.

“It was not uncommon for individuals to have had prior self-injurious events, past psychiatric diagnoses, and/or prior outpatient or other mental health care, although most completed suicides (n=52) did not have a reported diagnosed psychiatric disorder,” said the report. “The most frequently reported stressors included failed or failing relationships (especially marriage), legal problems, work-related problems, and excessive debt.”

Thirty-six percent of suicide attempts and 19 percent of completed suicides were by soldiers who had an outpatient mental health visit within 30 days of the event.

Perhaps the most controversial finding in the Army's report was that 55 percent of the completed suicides in 2006 were associated with failed marital relationships and another 14 percent with failed, nonspousal relationships.

“Based on past research, relationship problems and personal resilience are primary causes of a range of dysfunctions, from [being] AWOL, through family problems, to suicide,” said military sociologist David Segal, Ph.D., a professor at the University of Maryland. Deployment plays a role, but not a primary one.

“Resilient people in strong relationships are likely to weather repeated deployments well, particularly if they are members of the active forces,” Segal told Psychiatric News. “By contrast, soldiers low in resilience, who are in troubled relationships, are more likely to be affected negatively by the stress of deployment, or any stress.”

Several veterans' organizations have protested that the report's conclusions place too much blame on spouses and relationships while ignoring the family strains induced by 12- to 15-month separations.

“Longer, repeated tours are increasing the risks,” wrote Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America executive director Paul Rieckhoff on the Military.com Web site. “Our troops are facing serious mental health problems, and they aren't getting the treatment they need.”

Ragan agreed. “Saying that suicide doesn't reflect the effects of multiple deployments stretches the bounds of credulity,” he said. He also noted that while numbers were small, the rate of completed suicide among women (n=10) in the Army was twice that of U.S. women aged 17 to 45.

The Army also used a general suicide rate for the United States as a comparator, but there is considerable geographic variation, possibly reflecting the difficulty of accessing care in rural areas, said Ragan.

“Nevertheless, by the Army's own criteria, this is a significant elevation of suicide,” he said.

Deployment can create strains on relationships in many ways, especially among the youngest soldiers, who have had the briefest married lives, said Ragan: “You have an emotional connectedness with your wife. You're close beforehand, then you both learn to live apart, and then when you return, the distance has to be dealt with.”

The longer-term implications of the

2006 suicide figures will depend on whether they represent a trend or an exception.

“Regarding the possible rise in suicides, one would want at least five years of data to examine time trends,” said McFarland, coauthor of a recent study on suicide among male veterans.

Finally, sociologist Segal argued for caution in tracing the roots of military suicides.

“It is such a rare event that it is difficult to pin down its antecedents statistically,” he said.