Difficult kids lead difficult lives, depressed kids lead psychologically vulnerable lives, but good readers have a better chance of avoiding trouble and its aftermath, according to a 15-year prospective study connecting childhood personality and behavior to later trauma exposure.

Researchers from Johns Hopkins University and Michigan State University studied 2,311 children who entered first grade in the mid-1980s in a large mid-Atlantic city and followed them until young adulthood. About 67 percent were members of minority groups, 52 percent received subsidized or free lunches (an indicator of poverty status), and there was about an equal number of boys and girls.

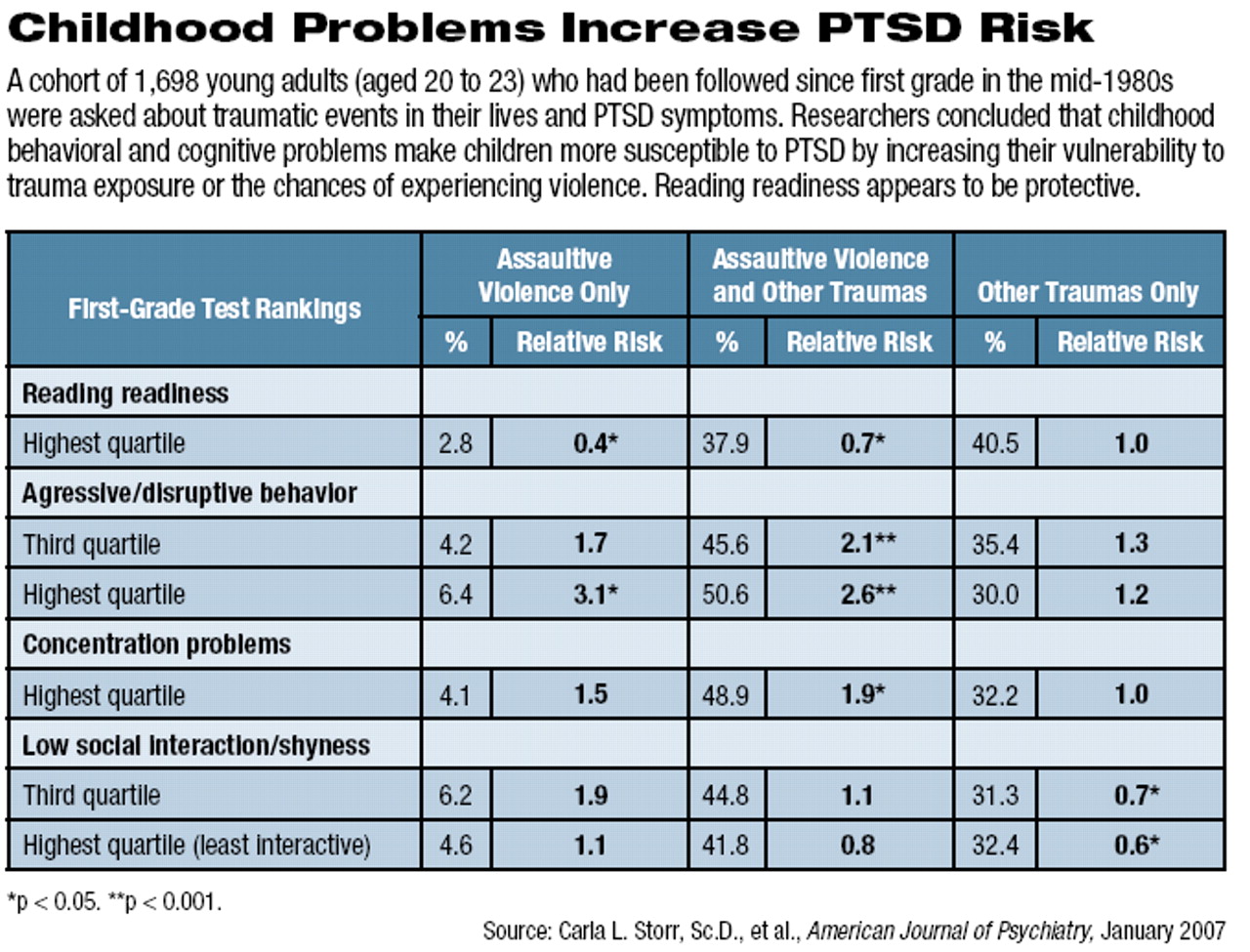

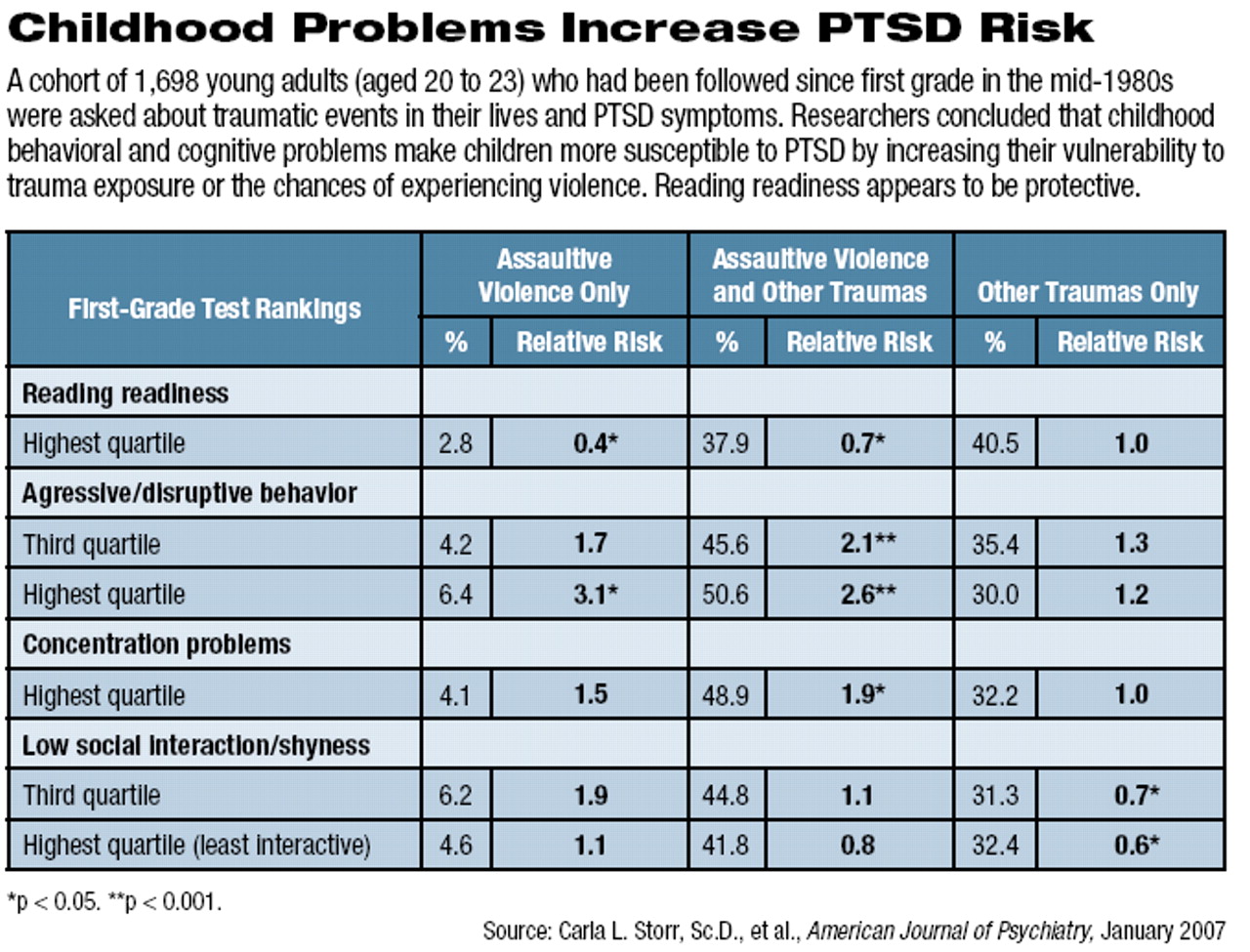

When they entered school, the students were evaluated by reading-readiness tests, depression and anxiety self-reports and by their teachers for aggressive or disruptive behaviors, concentration problems, and low social interaction or shyness. When the students were between the ages of 20 and 23, the 1,698 available for follow-up (about 75 percent of the original group) were interviewed about traumatic events in their lives and PTSD symptoms. Traumatic events included assaultive violence (such as being raped, beaten, or shot) and other experiences such as serious accidents, natural disasters, or hearing of a close friend's or relative's injury or unexpected death.

An estimated 82.5 percent of these children experienced one or more DSM-IV qualifying traumatic events in their lives. Among that group, 47.2 percent experienced assaultive violence.

“We found that the occurrence of traumatic events up to age 6-7 was less than 1 percent, and that age-specific occurrence rose markedly after age 15, with the highest rate observed between 16 and 18 years of age,” said Carla Storr, Sc. D., and Nicholas Ialongo, Ph.D., of Johns Hopkins University and James Anthony, Ph.D., and Naomi Breslau, Ph.D., of Michigan State University. Their findings appear in the January American Journal of Psychiatry. Grants from the National Institute of Mental Health and National Institute on Drug Abuse funded the study.

Teacher ratings in the first grade of aggressive or disruptive behavior that fell into the highest two quartiles pointed to nearly double the risk of exposure to an assaultive event, but not to other traumatic events in the absence of assaultive violence.

Children in the highest quartile of concentration problems were also at higher risk for exposure to assaultive violence, but not other kinds of trauma. Those with the highest reading-readiness scores were less likely to experience assaultive violence than were children scoring in the lowest quartile.

About 8.8 percent of children who experienced a traumatic event developed posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). There was an association between risk of PTSD and first-grade levels of anxious or depressive mood (relative risk=1.4), but it was not statistically significant.

“The results suggest potential risk factors for PTSD that can be identified early in life and might be amenable to interventions,” the researchers noted.

In a separate long-term study, Breslau, Victoria Lucia, Ph.D., and German Alvarado, M.D., M.P.H., all from the Department of Epidemiology at Michigan State University, examined the relationship of IQ measurements to trauma and PTSD. That study appeared in the November 2006 Archives of General Psychiatry. It included children randomly selected from 1983-1985 discharge lists of one urban and one suburban hospital in southeast Michigan and was originally designed to look at the sequelae of low birth weights in the communities served by the hospitals. Of the 823 children enrolled in the study, 713 were followed until age 17. Breslau and her colleagues adjusted their results to account for a disproportionately high percentage of children born at less than normal weight.

The most common traumatic event in this cohort was learning of the sudden, unexpected death of a close friend or relative. Traumatic events occurred more often among boys than girls and more often among urban than suburban youth.

The researchers found that children who had an IQ of at least 115 at age 6 were at lower risk for exposure to traumatic events or assaultive trauma or to have PTSD by age 17.

Exposure to traumatic events and PTSD was determined at age 17 through a computerized version of the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule. After all lifetime DSM-IV-qualifying traumatic events were identified, respondents selected the worst event they had experienced. DSM-IV algorithms were then applied to diagnose PTSD. Above-normal ratings of externalizing problems for 6-year-olds indicated increased risk of exposure to assaultive violence.

The researchers did note that while high IQ—at least one standard deviation above the population mean—appeared protective against PTSD, lower than normal IQ did not increase risk.

At present, Breslau told Psychiatric News, she can only speculate about the mechanisms by which reading or higher IQ (which are related) are protective. For instance, people with higher IQs may become better educated and take greater care to avoid potentially traumatic events. Or they may be able to cope better after experiencing trauma.

“If exposed to a difficult situation, they face a cognitive challenge to their views of themselves and their world, but they may tell themselves, I've solved problems before, I'm capable, I can handle this situation,'” she said.

Children with behavioral problems may choose more dangerous peers or take more risks, making them more likely to become victims of crime or accidents.

This IQ-PTSD link applies to both urban and suburban youth, she noted.

Breslau, a sociologist and psychiatric epidemiologist, is continuing to analyze study data to track the interaction of cognitive abilities, conduct problems, and emotional problems through the elementary-school years. Conceivably, better understanding of predisposing factors for trauma and PTSD may allow early interventions that could lessen their risk as the child passes through life.