British researchers have found evidence that suggests artificial food colors and additives may exacerbate hyperactivity in children, according to a study published online in The Lancet on September 6.

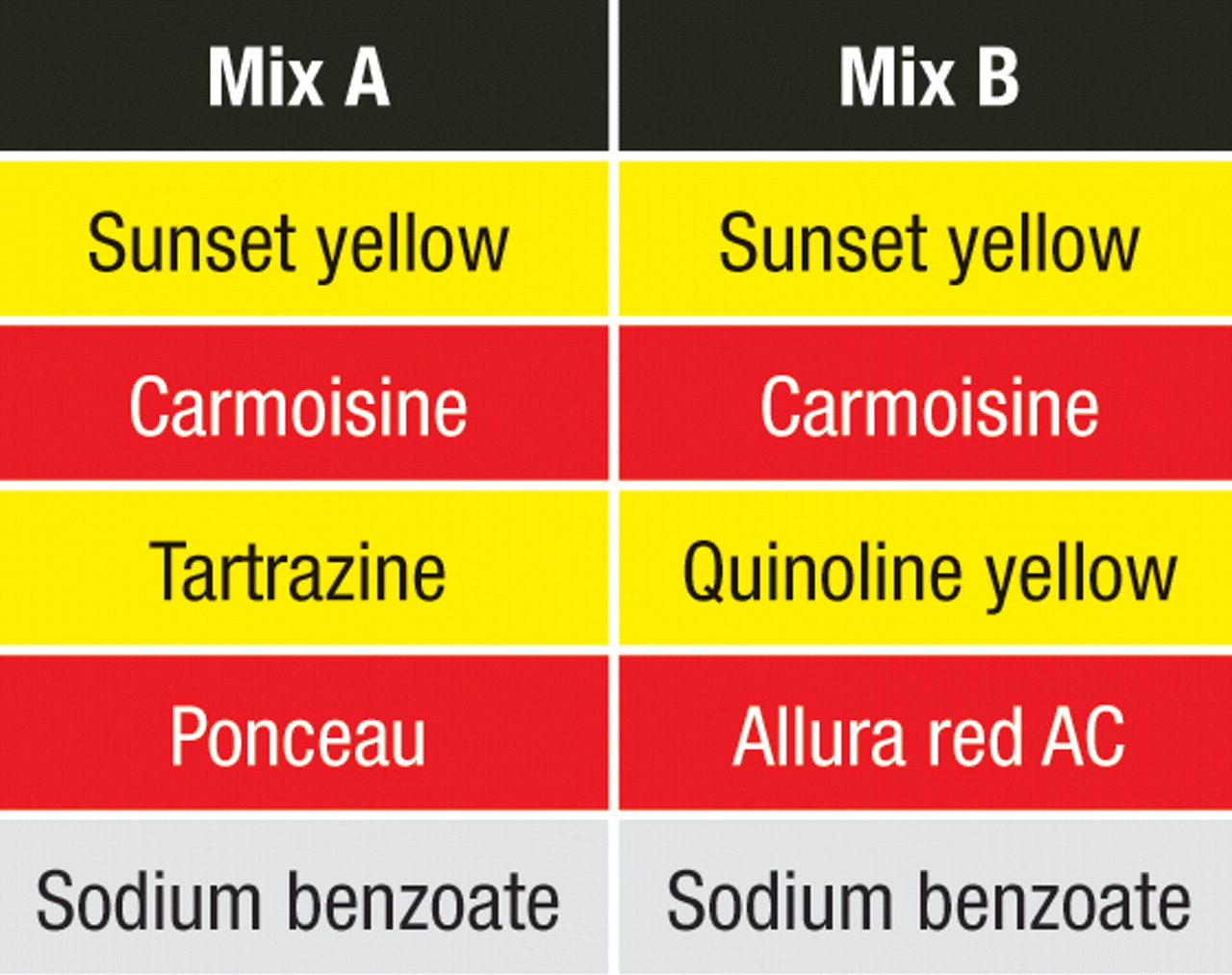

Donna McCann, Ph.D., and others from the University of Southampton in England, tested the effects of commonly used food coloring agents and the preservative sodium benzoate on hyperactivity levels in two groups of children: one group consisted of 153 3-year-olds and the other of 144 8- and 9-year-olds. During the six-week study with a within-subject cross-over design, the children consumed a set amount of drink mix every day. The drink mixes used in the study were three mixed fruit juices (two active mixes and one placebo) that looked and tasted the same; the only difference was that the two active drinks contained a mixture of artificial food colors and sodium benzoate (see

box for ingredients in the active mixes).

Each week, one of the three drink mixes (active mix A, active mix B, or placebo) was delivered to the children's homes for their consumption during that week. On weeks 2, 4, and 6, mix A, mix B, and placebo were delivered in a random sequence. The actual drink delivered to each home at any given week was blinded to the child, the parents, the teachers, and the researchers. Weeks 1, 3, and 5 were washout periods when the children received the placebo drink.

The children's behavior was measured throughout the study period using a global hyperactivity aggregate (GHA) score. The scores were compiled based on observation and ratings by parents and teachers. The children, parents, teachers, and researchers were unaware of the actual drink (active or placebo) given to the children at any given time. The study was commissioned by the U.K. Food Standards Agency (FSA), which regulates food safety.

The children had statistically significant increases in GHA scores associated with the active drink mixes in most but not all analyses. Among the 73 3-year-olds who did drink more than 85 percent of the assigned mixes in all six weeks and had all the GHA scores, and after controlling for several potentially confounding factors, mix A had a significant effect on GHA scores compared with placebo. Mix B, however, did not have a significant effect compared with placebo. Among the 91 8- and 9-year-olds who drank more than 85 percent of the assigned drinks, both mix A and mix B had a significant effect on their GHA scores compared with placebo.

“This is a very important study, rigorously designed by outstanding investigators, and represents an important cautionary note on the need for more studies of the impact of various food additives on children's behavior,” psychiatrist Peter Jensen, M.D., the director of the REACH (Resource for Advancing Children's Health) Institute, commented to Psychiatric News. “While it could not be determined from this study alone that such additives have a causative role in ADHD, the findings do suggest that additional, similarly carefully designed studies are needed in children generally and in children at risk for ADHD specifically.”

Previous studies had implicated artificial food colors and additives in increased hyperactivity in children with ADHD. In contrast, this study recruited a representative sample of children in the community with and without ADHD and showed increased hyperactivity within the overall study population.

Because of the composition of the active drink mixes, the authors acknowledged that it was not possible to parse out an individual additive's effect on hyperactivity. They pointed out that sodium benzoate has an important preservative function, and the implication of these findings could be substantial for the food industry.

If these findings are replicated by other investigators and in other populations, said Jensen, regulatory agencies should scrutinize the risks of the widespread use on such additives in foods. Based on this study, the FSA recently updated its advice to consumers, BBC News reported.

“If [children show] signs of ADHD, then eliminating the colors used in the Southamptom study from their diet might have some beneficial effects,” said Andrew Wadge, director of food safety policy and chief scientist at the FSA.

Both Wadge and Jim Stevenson, Ph.D., senior author of the study and a professor at Southampton University, both acknowledged that many other factors contribute to ADHD and simply eliminating artificial food colors and sodium benzoate will not necessarily prevent hyperactivitiy disorders.

An abstract of “Food Additives and Hyperactive Behaviour in 3-Year-Old and 8/9-Year-Old Children in the Community: A Randomised, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial” is posted at<www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140673607613063/abstract>.▪