In 1994 some 1,000 older Catholic priests, nuns, and brothers signed up for a mission that had nothing to do with saving souls but plenty to do with preventing illness.

The mission was called the Religious Orders Study. They were evaluated medically, neurologically, cognitively, and psychologically and have been tracked since to see which ones develop Alzheimer's disease. Differences between those who develop Alzheimer's and those who do not are then being analyzed to identify factors that might predict subsequent susceptibility to Alzheimer's.

One of the factors that the study has identified is rapidly progressing Parkinson's disease (Psychiatric News, June 20, 2003). Still another is neuroticism, that is, an enduring tendency to experience psychological distress (Psychiatric News, July 20). And now still another has been suggested—that a higher level of conscientiousness is linked to a reduced risk of developing Alzheimer's.

The lead author of this latest assessment, as well as the previous ones, was Robert Wilson, Ph.D., a professor of neuropsychology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago. Results were published in the October Archives of General Psychiatry.

In 1994 Wilson and his group used the NEO Five-Factor Inventory to assess five personality characteristics in the study participants. One of these characteristics was conscientiousness, which, as the researchers pointed out, means a tendency to be self-disciplined, goal directed, willing to work, painstaking, and dependable.

Study participants read 12 statements concerning conscientiousness, such as“ I am a productive person who always gets the job done,” then rated themselves on a scale of 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating more conscientiousness. The highest possible score was 48. The participants had conscientiousness scores ranging from 11 to 47, with an average of 34.

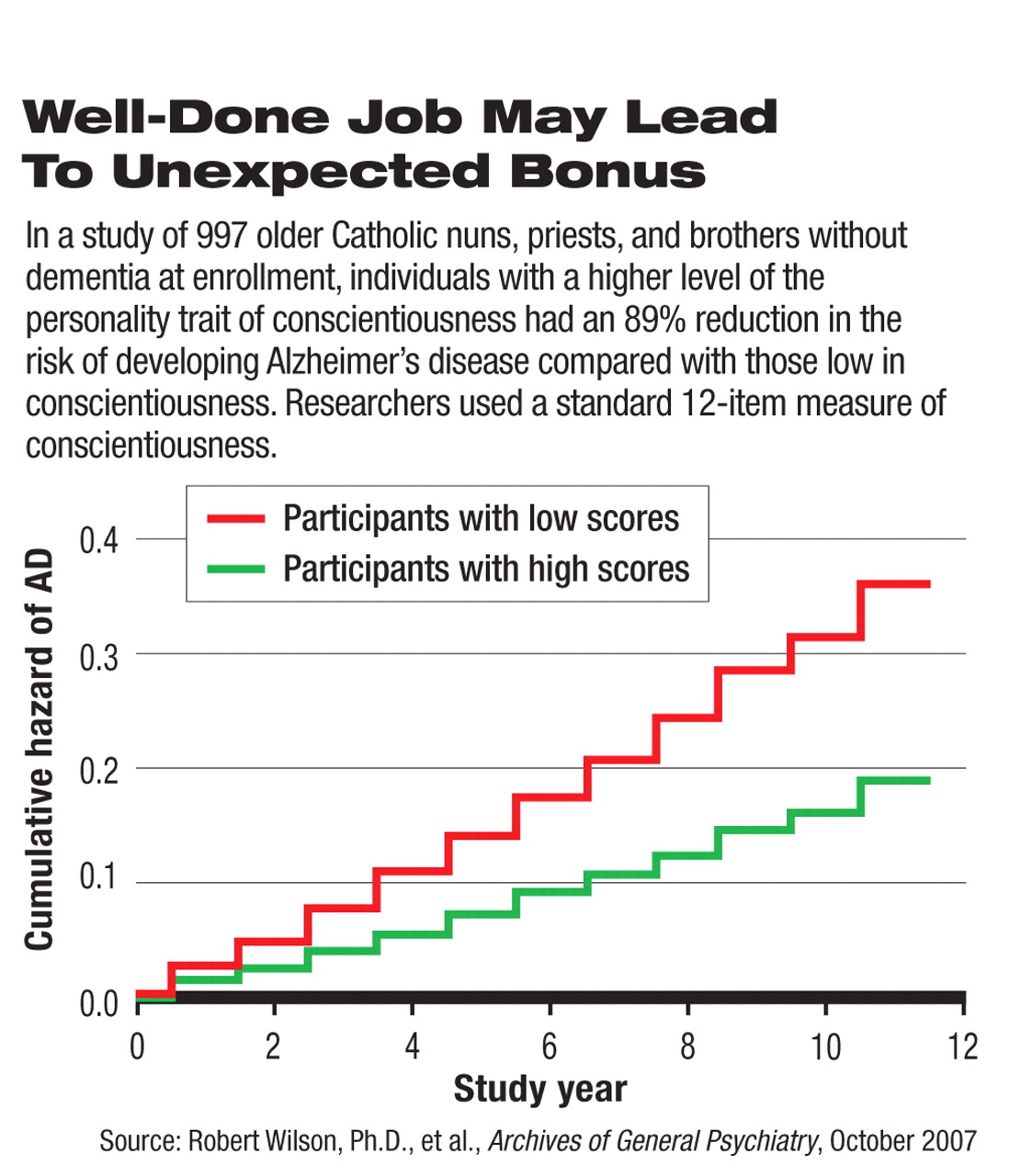

By 2006, 12 years after the study started, 176 of the study participants had developed Alzheimer's disease, and the researchers assessed whether there was any link between study participants' conscientiousness scores at the start of the study and their susceptibility to Alzheimer's during the 12-year follow-up, taking three factors known to influence Alzheimer's—age, gender, and education—into consideration.

Their Alzheimer's risk decreased by more than 5 percent for each additional point they obtained on the conscientiousness yardstick. Thus, those subjects who had conscientiousness scores in the 90th percentile (40 points) or higher at the start of the study, had an 89 percent lower risk of developing Alzheimer's than did those whose scores had ranked in the 10th percentile (28 points) or lower at the start of the study.

The researchers then repeated their analysis, taking other Alzheimer's risk factors into consideration. The factors were neuroticism, physical activity, cognitive activity, size of the social network, possession of the APOE-e4 gene variant, vascular disease, depressive symptoms, and mild cognitive impairment. Again the link between conscientiousness and risk of Alzheimer's held firm.

However, the reason why conscientiousness seems to augur protection against Alzheimer's is not clear, Wilson and his group acknowledged, noting that conscientiousness seems to be protective against other mental and physical illnesses as well, “suggesting that the trait has some general role in health maintenance.”

The role may have something to do with safeguarding cognition, the researchers suggested. This might be the case, they explained, because at the start of the study, the cognitive skills of highly conscientious subjects were comparable to those of less conscientious ones, yet as time went by, those skills declined much less in the more conscientious individuals.

But how might conscientiousness help safeguard cognition? Conscientiousness has been linked with a higher level of resilience and greater reliance on task-oriented coping, the researchers pointed out. Thus these factors might buffer cognition from the adverse consequences of negative life events, and cognition shielded from such adverse consequences might then be better armored against Alzheimer's, they proposed.

“Understanding the mechanisms linking conscientiousness to maintenance of cognition in old age may suggest novel strategies for delaying the symptoms of Alzheimer's disease,” Wilson and his team concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging.