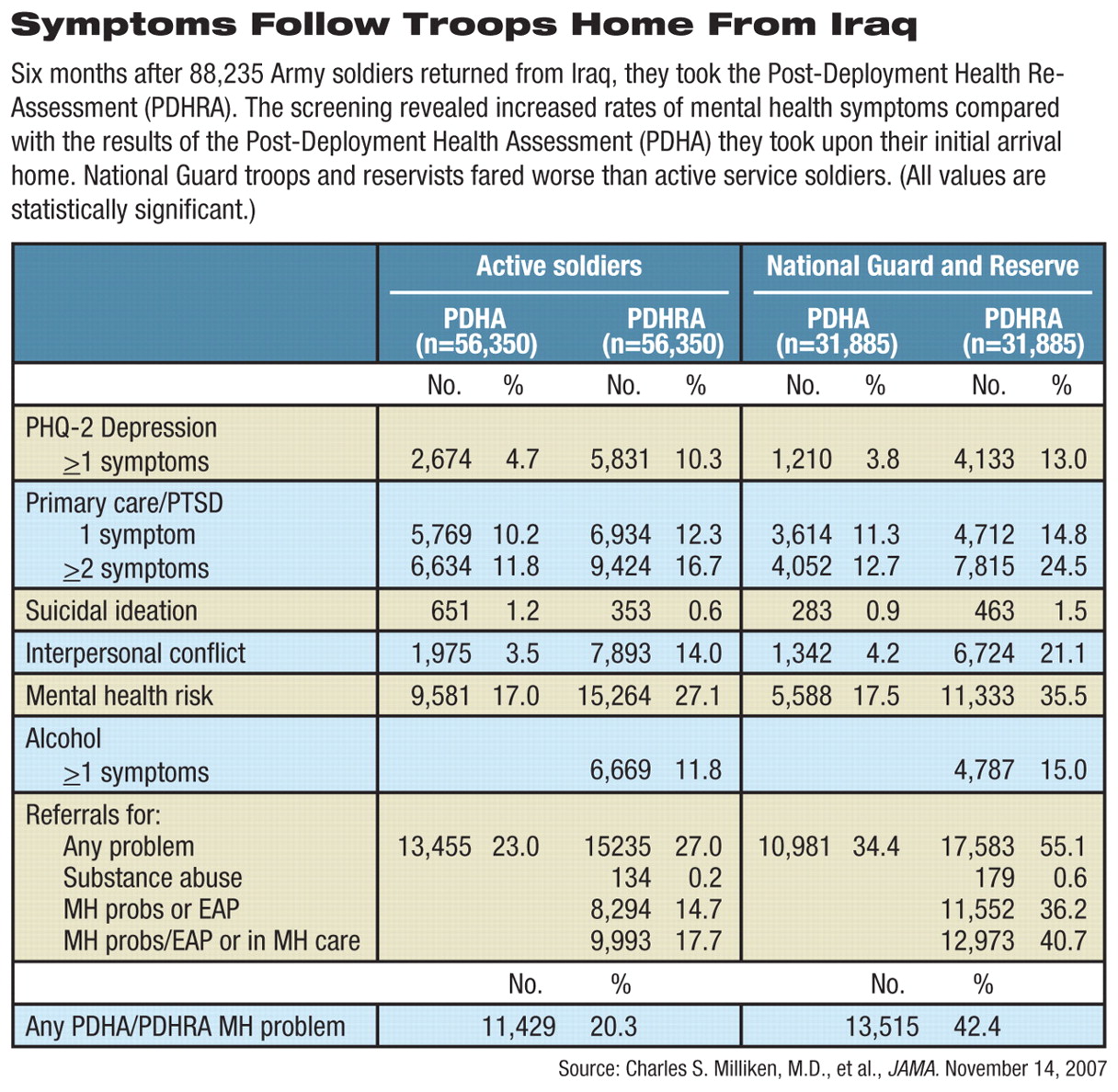

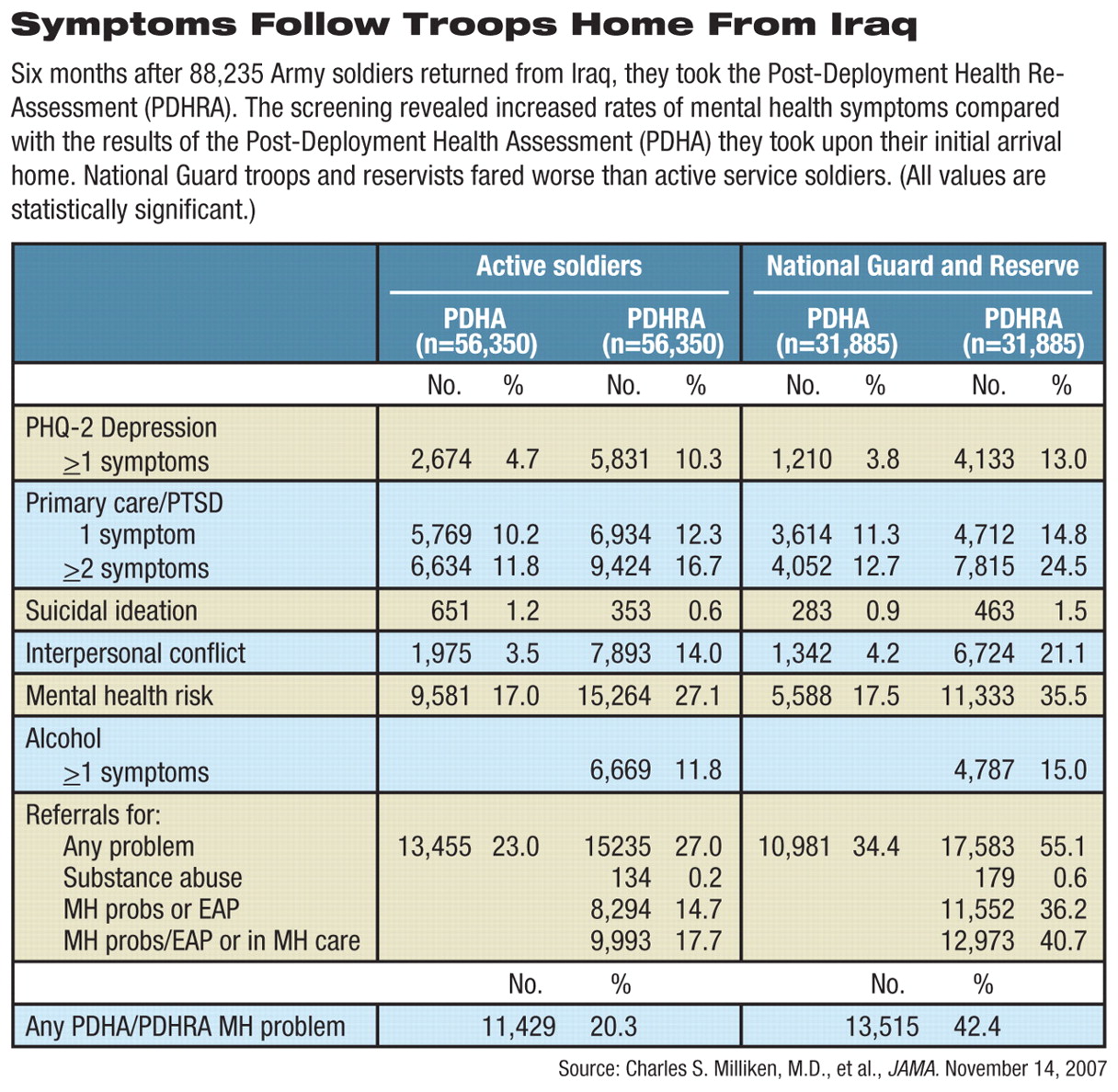

Soldiers back from Iraq report more mental distress after they've been home for six months than when they first return, and National Guard and Reserve soldiers are twice as likely to need mental health care as their regular-Army peers, according to an Army study.

The study compared health assessments of 88,235 soldiers given just as they returned from the war zone with their responses to a similar evaluation four to 10 months later.

“The rates that we previously reported based on surveys taken immediately on return home from deployment substantially underestimate the mental health burden,” said Col. Charles Milliken, M.C., Jennifer Auchterlonie, M.S., and Col. Charles Hoge, M.C., in the November 14 Journal of the American Medical Association. Milliken and Hoge are psychiatrists. Hoge is director of the division of psychiatry and neuroscience at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, and Milliken is a principal investigator there.

The new study compared results from the Post-Deployment Health Assessment, or PDHA, which is the screening questionnaire that troops must take as they return from overseas deployments. The same authors published a report in March 2006 documenting responses on the PDHA of 303,905 Army soldiers and Marines who had served in Iraq and Afghanistan. Their current study is based on a second round of screening with the Post-Deployment Health Re-Assessment (PDHRA), which was completed between June 1, 2005, and December 31, 2006, and covers only U.S. Army soldiers who served in Iraq (Psychiatric News, April 7, 2006). Both surveys ask soldiers to answer questions on their health, followed by a brief interview with a physician, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner. The survey results become part of the soldiers' military health record and can be evaluated later, along with all episodes of care.

MH Care Needs Extensive

Higher rates of psychological symptoms reported in the second assessment might be considered a positive sign that the Army is finding symptoms that arise later or were concealed in the first survey. Recognizing symptoms early could allow earlier intervention and a less severe course of any disorder, said Milliken at the briefing. However, some findings may also reveal shortcomings in the existing military mental health care system.

Soldiers were considered to be at mental health risk if they screened positive for some items related to depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, suicidal ideation, and interpersonal aggression and conflict. Overall, mental health risk for active component troops was 17 percent as they returned from Iraq and 27 percent on average of six months later; the risk for National Guard members and reservists rose from 17.5 percent to 35.5 percent. There were also significant jumps in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression symptoms in the six months between the two screenings.

Soldiers with high rates of depression or PTSD symptoms in the first round often showed symptomatic improvement by the second screening, but there was a doubling of new cases among those who had had normal scores on the PDHA.

When the results of the two screenings were combined, 20 percent of active and 40 percent of National Guard or Reserve soldiers required mental health treatment.

By comparison, a compulsory screening of 1,442 Canadian land, sea, and air force members who served in Afghanistan found that four to six months after their return, 20 percent had symptoms of at least one mood, anxiety, or alcohol use disorder. Follow-up interviews led to referrals for 23 percent of the total, mostly for psychosocial issues, according to a study by Mark Zamorski, M.D., of the Canadian Forces Health Services Group Headquarters.

Interpersonal Relationships Suffer Most

Only 1.1 percent of the U.S. soldiers received a mental health referral after taking both the PDHA and PDHRA, implying that new symptoms developed in the half year after returning from Iraq or reflecting an unwillingness to admit symptoms immediately upon arrival for fear of delaying home-coming or harming a career.

The sharpest increases were reported for interpersonal conflicts at home or work, rising from 3.5 percent to 14 percent among active component troops, and from 4.2 percent to 21 percent among Guard and Reserve soldiers.

The fourfold increase in the last category “highlights the potential impact of this war on family relationships,” said the authors. It also highlights the fact that family mental health care is not available on military posts as is other routine health care. Spouses and children must turn to the TRICARE contractor insurance network, a system described as“ inadequately resourced, inconvenient, and cumbersome” by a review panel earlier this year.

“When soldiers come back for the first time, they're just glad to be home,” said Brig. Gen. Stephen Jones, M.C., assistant surgeon general for force projection, suggesting one explanation for the difference at a news briefing announcing the results of the survey. “But then they re-enter family relationships, and stress levels at home go up.”

Milliken and colleagues were also critical of the Army's handling of reported alcohol problems. Although 6,669 of the 56,350 active troops said they had alcohol problems, only 134 were referred for further services, and only 29 actually sought help within three months. This finding may reflect current military policy on alcohol misuse, they said. Mental health standards attempt to balance confidentiality with an officer's need to know whether a soldier is fit to serve. However, “accessing alcohol treatment triggers automatic involvement of a soldier's commander and can have negative career ramifications if the soldier fails to comply with the treatment program.”

Barriers to Care Noted

Active component troops and Guard or Reserve soldiers reported similar levels of combat exposure when they first returned, so the different rates of symptoms they reported in the later screening may be due to other circumstances, primarily lack of access to health care, said Milliken.

“Active soldiers can get care on the base, but more than half of the Guard or Reserve soldiers had passed the time in which they were eligible for care through the Department of Defense,” he said. Reservists may also lack the close support from unit members after they come home and face stresses in a sudden return to civilian jobs.

The researchers also noted an apparent inverse relationship between treatment and improvement in PTSD symptoms, an anomaly that, said the authors,“ may indicate that treatment for PTSD is not optimal in military health clinics because soldiers are not receiving a sufficient number of sessions or the provided treatment is ineffective.”

Several encouraging points were identified in the new study, said Milliken and Jones at the briefing. For example, 61 percent of active soldiers referred for care received services, and most who sought services on their own did so within 30 days of screening.

For soldiers with symptoms that earlier were not considered serious enough to warrant referral, simply filling out the PDHRA may have spurred the decision to visit a clinician, said the authors.

Army brass and medical officials have also taken steps in the years since the recent conflicts began to decrease the stigma associated with having or reporting symptoms of psychological stress. They stepped up programs to educate troops about mental health issues and the inevitable stresses of deployment and combat. Soldiers now hear that help seeking is a sign of strength rather than weakness. Last summer, the service required leaders at every level to learn and then teach their subordinates about PTSD and traumatic brain injury. These efforts may have helped soldiers filling out the PDHRA to acknowledge their mental health needs and ask for help, said Milliken.

Conducting the screenings and studying their value during wartime was a new step for the Armed Forces, he said. “The Army's efforts to care for the mental health of soldiers through early identification, early treatment, and education during this conflict are unprecedented.”